By Susan Hand Shetterly

Photographed by Gabor Degre

From our January 2010 issue

Wayne Newell was seven years old in 1949 when a cataract surgeon at the Maine Eye and Ear Infirmary in Portland unwrapped the postoperative bandages from his eyes. He opened his right eye — the left one had never worked — and the world was different. For the first time he saw more than fuzzy shapes and shadows. “My God! Everything was so clean.”

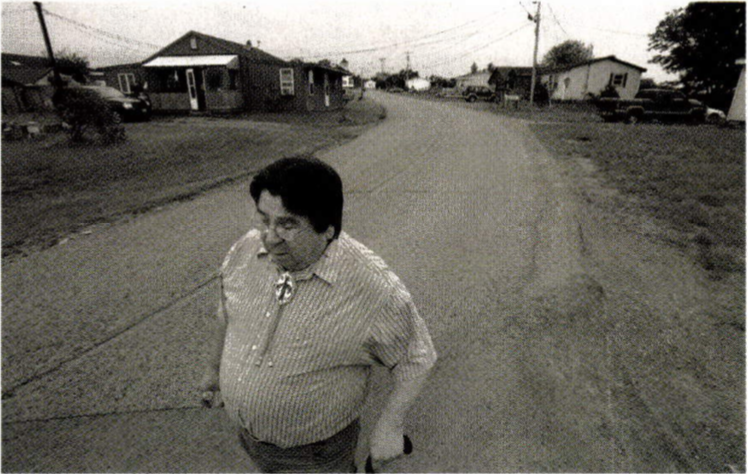

Now a Passamaquoddy elder and the director of bilingual education at the elementary school in Indian Township, north of Calais in Washington County Newell has never forgotten the revelation that things can change — that transformation is genuinely possible. Yet, even today he can still make out the edge of that old childhood cataract pinned back within the upper lid. You might say he is a man who has the capacity to see both the present and vestiges of the past at the same time.

Newell was born an hour south of Indian Township, at Pleasant Point on Passamaquoddy Bay, in a two-room tarpaper shack. He grew up in poverty as did all his neighbors, and struggled through school and with the venomous, quotidian racism of the time. A child who was close to his family, he was, nonetheless, isolated by his poor eyesight from other kids his age and all the things they were leaming to do: hunting, cutting wood, pounding black ash for basket making, and, eventually driving.

“I could see, but I was still legally blind,” he explains. “My eyesight with glasses is 20/200. It is what it is, and I’ve never regretted it. But there were all sorts of things I knew that I couldn’t do. Something told me, ‘You’d better figure out what you want because you can’t do what your buddies do.’ Maybe the good Lord decided to give me a little insight early.”

No one in his family encouraged him to go to the reservation school taught by nuns. “My grandmother and mother didn’t see the necessity of the schoolhouse. The school wasn’t our institution,” Newell says. Instead, he learned from the inside: from people who told him stories about what it means to be Passamaquoddy. His family taught him to distinguish between the poverty they struggled against and the culture they embraced.

But he got lonely learning at home. One day he walked into a classroom at the reservation school and sat down. He didn’t want to be left out anymore.

“Education was the great liberator,” Newell says. By ten years old, he had leamed enough English to be a passionate reader, but he never lost Passamaquoddy.

“I’ve always been very lucky I’ve always been in the right place at the right time,” Newell says, leaning forward in his office at the Indian Township Elementary School and putting the palms of his hands firmly against the papers piled on his desk. The pediatric cataract surgery that gave him sight, for instance, was then a new technique. He entered the reservation school just as it began receiving aid for the blind and was offered books in large print as well as records and tapes. In high school, after flunking out his sophomore year, he came back to repeat the grade the next fall, and before he graduated, won first prize in a public speaking competition.

Gifted with a sonorous voice, he had hoped for a career as a radio broadcaster. At Emerson College in Boston he studied public speaking, but he struggled with writing assignments and eventually dropped out. He dropped out of Ricker College for the same reason. Newell came back home and found a job in Bangor as a cameraman at a local television station. “I was probably the only legally blind TV cameraman in the whole country,” he laughs.

Newell has influenced all the teachers writers and musicians who are working with the language today.

It was at the TV station that he first heard John Stevens, the Passamaquoddy governor, speak to a broad audience. Although Stevens — translating himself into English from his native Passamaquoddy — was an uneven public speaker, he was a smart, courageous, principled man, arguing for Indian rights. His example inspired the young cameraman, and Newell resolved to tum his life around.

In short order, he married and won a Ford Fellowship for leadership development that allowed him to spend a year in Washington, D.C., as an intern at the Economic Development Administration. He studied economic issues — “to learn ways to help my community so we wouldn’t be so poor” — as well as the histories of other Native American communities. In his spare time, he volunteered in the office of Senator Edmund S. Muskie. No sooner did Newell return to Maine than he was told by Ed Hinkley, the state commissioner of Indian Affairs, that he should apply for a master’s degree at the Harvard School of Education in a new program that was recruiting community organizers.

Newell just laughed. “Ed,” he said, “I don’t even have a bachelor’s degree — and you want me to apply to graduate school at Harvard?”

Hinkley countered, “Make a case for Iife experience.”

That night Newell sat down and began to write about his own life and his hopes for his people. The next morning, his wife, Sandy, typed his pages and sent them off, and by return mail, he was invited to Cambridge for an interview.

“I said to myself — Harvard — I can’t go looking like a bum. I bought a beautiful suit, thinking that this is how they want me to look.”

Newell arrived at the campus during the height of the demonstrations against the war in Vietnam.

“I get there, and the cops had been clearing the Yard the night before,” he says. “I am on my way to this committee that is going to interview me. I open the door to the room, and the first thing I see is all these men sitting around a big table, and they have beards and are wearing flannel shirts and jeans. Oh, my God! I’m standing in front of them dressed like an undertaker!” He gives a roar of laugher at the memory.

Harvard accepted Newell into the program, and he moved to Cambridge with his wife and child in 1970. Soon he had cross-registered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was studying the problems of constructing a writing system for an oral language with the linguist Dr. Kenneth Hale. Dr. Karl Teeter, the Harvard linguist, had already worked on transcribing Passamaquoddy Newell asked if he could build on that work and reshuffle some of the sound systems: “I told him I’m not a linguist, but I want to go back to Maine and teach my people to write our language as a part of trying to save it. Dr. Teeter said, ‘Go right ahead.’ And I did.”

After a year in Cambridge, Newell was hired to run a demonstration program in bilingual education at the elementary school at Peter Dana Point in Indian Township. It was funded by a small government grant. Halfway through the year, the government offered to fully fund the program at a hundred thousand dollars. “My jaw dropped. I’d never managed that kind of money. Before I got a chance to say, ‘No,’ I said,’Yes.’ My job, as I saw it, was to include the Passamaquoddy language in every classroom.

“In other parts of the world, being bilingual or even trilingual is no big adventure, but here in America we have this very narrow view of what people should be.”

For his part, Newell continues to direct the language and culture program at the Indian Township Elementary School, although he took a few years off to help set up a health clinic on the reservation. He is also the president of Northeastern Blueberry Company, a tribally-owned business and, at two thousand acres, one of the largest growers in Maine. In 2007, he was confirmed by the state legislature to serve on the University of Maine’s Board of Trustees.

In February of last year, Newell saw his life’s work validated with the publication of The Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Dictionary: Peskotomuhkati Wolastoqewi Latuwewakon. It is an elegant volume of 1,200 pages, published by the University of Maine Press.

David A. Francis, one of the authors who worked with Newell teaching Passamaquoddy, is ninety-one years old. Another, Robert M. Leavitt, professor emeritus at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, first met Newell at Harvard in 1971. “Wayne has been the inspiration and driving force behind all efforts to revitalize the Passamaquoddy language in Maine,” Leavitt says, emphasizing that Newell deserves the lion’s share of the credit for the dictionary “He initiated and oversaw both the Passamaquoddy dictionary project and the creation of countless recordings, books, and teaching materials based on traditional storytelling, music, and oral history.” Although the dictionary has taken decades, as Newell suggests in his introduction, it has been, for all of them, a race against time.

“What would help future generations continue learning and speaking the language?” he writes. And, of course, this is the question that riles the heart of his work: How do you save an oral language in peril?

“If we don’t get more people speaking fluently, we won’t have teachers for the next generation,” says Newell. “When the ball starts rolling the other way it doesn’t take long. My generation was immersed in the Ianguage, but we didn’t keep it up. We bought TVs. We wanted our kids to do well in the outside world — in the English-speaking world. We ended up bringing into our culture all kinds of challenges to it.”

Leavitt says Newell’s work focuses on restoring a cultural balance. “He continues to devote himself to the language and to education, not only for children but also for adults who understand Passamaquoddy and want to regain their fluency,” he declares. “He has influenced all the teachers, film-makers, writers, and musicians who are working with the language today.”

When Newell was young, poverty and racism kept his community isolated. Indian schoolchildren never brought white friends home to the reservation. “It was the shame thing, to be honest. We were at the bottom. Even poor white folk looked down on us. If a white child didn’t behave, parents would say, ‘I’m taking you up to live with those Indians.'”

Today, Newell says, white students come to the reservation school for track meets, basketball, and baseball games. “You don’t see the direct racial stuff anymore,” he says. He points to the open land at the back of the school and explains that this is where the community plans to build a state-of-the-art track and field complex, which will draw even more people to Peter Dana Point from outside the community.

“Our children are proud of being Passamaquoddy. We have children who can’t wait to grow up to do their solo dance for the community,” he says, smiling broadly. “With all the changes in the world you’d think there might be less interest, but, actually, there’s more.”

Yet every day Newell sees the most persistent and corrosive problems on the reservation undermine his work. Washington County has one of the highest unemployment figures in the country at 20 percent, but on the reservation it’s higher still. The only way we are going to come out of this is if we find a way to do it ourselves. We need jobs based right here.” Newell hires a number of the people he taught in the seventies to teach Passamaquoddy to the children today. But it’s not enough.

“We have the alcohol problem,” he explains. “And the drugs — like OxyContin — have crept up in the community. There are a few houses here where there is hardly a stick of furniture because the parents have sold off all their stuff for drugs. I see it in the children at school. They’ve been up all night. They haven’t been taken care of as well as the other children. This is a community that traditionally cares very much for its children. Drugs — they don’t care how they rob you!”

Newell believes that reservation children are especially hungry for good role models. When the Passamaquoddy governor, Robert Newell (no relation), was convicted on thirty counts of conspiracy to defraud the tribe last spring, Newell says simply, “It was devastating.” He is not referring solely to the crime of stealing, but to the crime of letting the children down.

Can a language and culture program stand up against all this? Can it protect or even save a person from some of the lethal parts of reservation life?

“This is a tough aspect to look at,” Newell says, “and it can burn you out.” But, he continues, that, yes, sometimes a few people break away from their addictions and embrace, instead, their heritage and study the native skills and ceremonies. They learn the language. “It’s a dramatic change,” he says. “It’s not easy, but it is not impossible.”