By Michaela Cavallaro

Illustration by Mike O’Leary

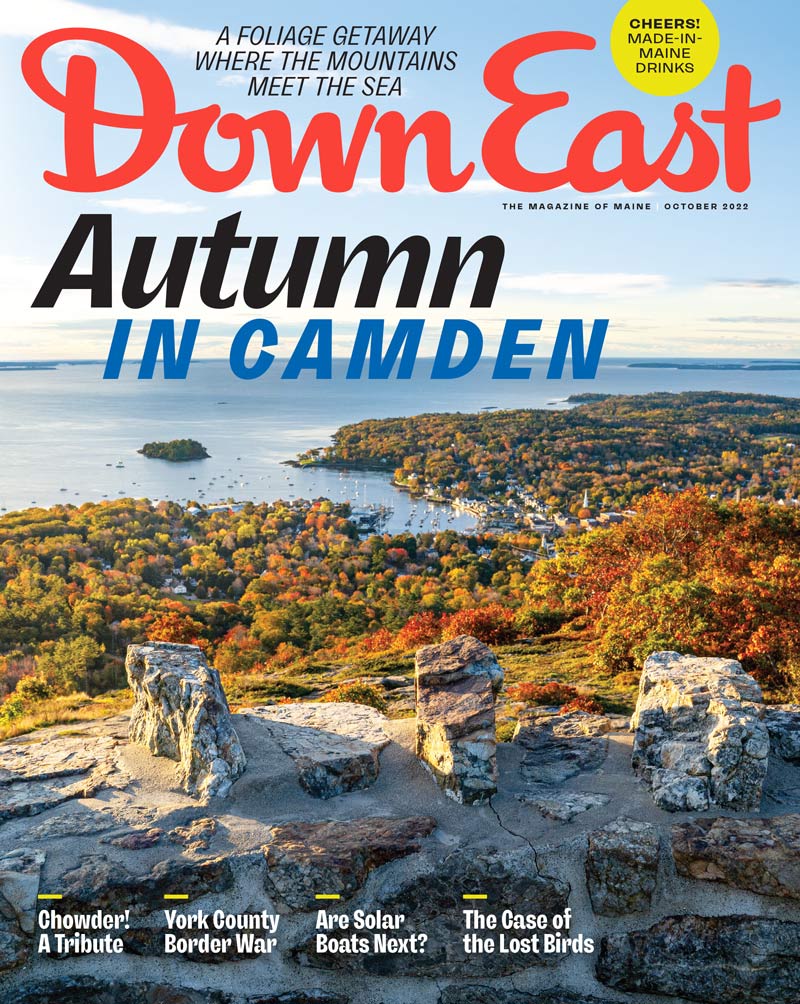

From our October 2022 issue

As boatbuilder Dan Miller drove west on Route 3 one Saturday morning in April, headed for Liberty’s Lake St. George, he harbored all the usual concerns of a shipwright on a sea-trial day: Would the powerboat his crew had just finished building come off its trailer smoothly? Would it float as expected on its waterline? Up ahead, the retired physics professor who’d commissioned the boat in question hauled it behind a pickup truck borrowed for the project. As Miller followed the gleaming white hull, he wondered whether its power system would work as intended. A lot was riding on that question, more than usual, because while Miller and his 16-person Belmont Boatworks crew are old hands at boatbuilding, this was the first time they — or anyone else — had ever launched a completely solar-powered fiberglass passenger boat.

With its sleek, slightly futuristic design and seating for 10 beneath a canopy covered with solar panels, the 24-foot craft had been built over the previous four months. But the project had been in the works for nearly two years, slowed by supply-chain delays and the many design tweaks necessary in any first-time build. So when Solar Sal took to the lake on Earth Day without a hitch, the launch marked a crucial step, both in the boat’s development and for Miller’s 10-year-old midcoast boatyard, which he hopes is poised to help lead a renewable-energy revolution in pleasure boating. “If we can prove this is possible — if somebody can make money on it — that will open the floodgates,” Miller says.

The Belmont Boatworks founder isn’t alone in seeing potential. An industry report published this summer valued the global electric-boat industry at roughly $5 billion in 2021 and predicts that number will grow to $16.6 billion in the coming decade. Passenger boats account for most of the projected growth, and although a few well-capitalized startups currently dominate the emerging market for zero-emissions powerboats, Maine’s marine industry is starting to take notice.

David Borton, the inventor and solar-power enthusiast behind Solar Sal, took notice earlier than most. Borton, who lives in Troy, New York, spent his childhood in canoes and Adirondack guide boats, shallow-draft wooden rowboats designed to be portaged by one person, and he got interested in solar energy during the gas crises of the 1970s, while pursuing a PhD at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. After he became a physics professor there, he taught classes on the emerging technology. “Because I understood the physics of both boats and solar, I realized I could make a practical solar boat,” Borton says. “So I patented it.”

He approached his development process methodically. Hiring designers to draw the plans and boatbuilders to handle the construction, Borton developed the technology for multiple iterations of what became Solar Sal 24, each responding to a particular criticism or challenge. Solar-boat skeptics tend to raise the same concerns as those dubious about electric cars or at-home solar, often centering on range (how far can I go on a charge?) and reliability (how do I get power on a cloudy day?). Borton started with a 25-foot wooden boat with solar panels atop the canopy. Then, after hearing a critique that solar could only work for small boats, he built a 40-footer. “I don’t consider that a small boat, but some people still called them my ‘toys,’” he says. “The only way I could get people to understand they were not toys was to make a Coast Guard–inspected, Coast Guard–certified commercial boat.” Today, that boat, Solaris, runs 100-percent solar-powered tours for the Hudson River Maritime Museum — and it travels up to 50 miles on reserve power alone.

Once Borton felt he’d nailed down crucial technical elements — efficient delivery of power from the solar panels to the engine, hull design that eases a boat’s movement through the water — he was ready to bring his solar-powered craft to a wider market. His goal, Borton says, is “to replace every fossil-fuel boat with a solar-electric boat.” To accomplish that, he switched from wood to fiberglass, in order to bring the price down and enable mass production, and he sought out boatbuilders who could handle the capacity he hopes he’ll need. Mainer John O’Donovan, a Belmont Boatworks carpenter who’d worked on the Solaris, introduced Borton to Miller. A self-described “tree-hugging hippie,” Miller was looking for a production boat project, and Solar Sal, named for a mule in an old folk song that pulls barges through the Erie Canal, was right up his alley.

Today, Miller’s team has two more Solar Sal 24s under construction in Belmont, scheduled for completion by the end of October. Like the first boat — now in dry dock, awaiting a buyer — they’ll be capable of traveling about 45 miles over nine hours at cruising speed on battery power alone. But since the battery is always recharging, even on cloudy days, the practical range is farther. Borton plans to take them to winter boat shows, in the hopes that pleasure boaters will like what they see enough to shell out $124,500 for a Solar Sal of their own. As Miller’s crews work on these next-generation crafts — right next to decades-old boats with tall wooden masts and diesel engines — they keep an eye out for design tweaks that might make Solar Sal easier and more efficient to produce.

Some 100 miles down the coast, in Biddeford, Maine Electric Boat Co. cofounder and president Matt Tarpey has pivoted from renting and selling electric pleasure boats to consulting on the development of working boats for aquaculturists, harbormasters, and marina operators. Like Borton, Tarpey is driven by an ambitious vision, this one set by the Rockland-based, nonprofit Island Institute, which aims to get 100 electric-powered skiffs on Maine’s working waterfront by 2025. Tarpey is partnered with Flux Marine, a Rhode Island start-up, to market small work boats that, unlike Solar Sal, use a dock-based electric charging system — a replacement for what he describes as the typical “30-horsepower Honda that might start about half the time — and when it does, it’s smelly and putting oil into the water.”

Since the electric engines can power a small boat at moderate speeds all day without a recharge, Tarpey says they’re well suited for a day of tending oyster beds or zooming around a marina. He’s optimistic that Maine’s marine workers will be eager adopters once they see the first few boats at work next year. Down the road, he expects enough demand that Maine Electric Boat will become an official dealer of the Flux boats. “There’s some trepidation and fear about new technology, especially the way it’s been talked about in the U.S., that it’s slow and somewhat unreliable,” Tarpey says. “My experience has been quite the opposite. But the aquaculture industry is seeing the effects of climate change firsthand, and they understand the problem.”

As emissions standards tighten and boaters increasingly look for quieter, cleaner watercraft, Stacey Keefer, executive director of the Maine Marine Trades Association, expects Maine boatbuilders to embrace zero-emission technology. But first, she says, more waterfront communities will need to install dock-based charging stations — enough of them to assuage electric-boaters’ anxieties about exhausting batteries and being unable to recharge. In the meantime, she sees an opening for all-solar boats like Borton’s. “Very few people have electricity right down to the water,” Keefer says, with lakefront property owners in mind. “That’s where I think Solar Sal would have a strong following.”

Back in Belmont, Miller and his team are expecting that following to grow steadily. “This isn’t a trend,” he says. “This is the future.”