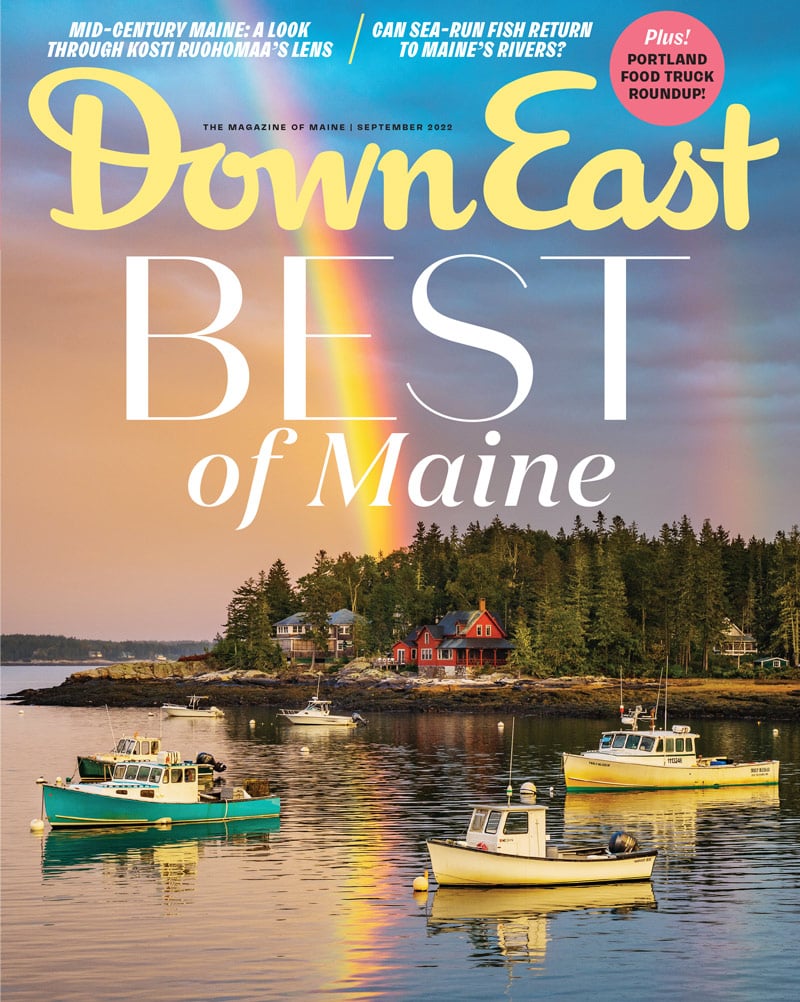

Postcard attractions for generations: the Old Gaol, the Emerson-Wilcox House, and Jefferds Tavern, which is now part of the Old York Museum Center.

By Brian Kevin

From our September 2022 issue

With its roots in the 19th century, the Old York Historical Society has a whole lot of years behind it, but the 12-month period between Memorial Day 2020 and 2021 was surely one of the lousiest. Two years ago, by the time the OYHS museums’ traditional opening day rolled around, it was clear that COVID would keep the doors shut all season long at the organization’s cluster of historic visitor properties. This was dispiriting, for a few reasons: OYHS had for years been planning a tercentennial celebration of its Old Gaol, arguably the most recognizable structure under its care, the stone nucleus of which was built in 1720. And it had only just wrapped a more than half-million-dollar restoration of its circa 1730 Elizabeth Perkins House, the one-time summer home of an early-20th-century upper-cruster and prominent civic booster. The museums pivoted to walking tours and, like the rest of us, muddled through that first pandemic year. In May 2021, OYHS announced a phased reopening: online reservations, timed entry, masks — but a reopening nonetheless. Then, over Memorial Day weekend, a car crashed through a Colonial Revival–style fence and into the front parlor of the 1735 Emerson-Wilcox House.

More than a year later, that building is still closed and unrepaired, the insurance wheels turning slowly (thankfully, the drowsy driver was unhurt). But the rest of the OYHS campus is enjoying its first fully open season since 2019, and some new developments during the intervening stretch have made it an exciting time for an organization that tends to some 20,000 artifacts and 50,000 archival materials, tracing the history of Maine’s longest-settled region. Below, a few updates on what’s new in Old York.

NOW EVEN YORK-IER

The story of York begins 400 years ago, in August of 1622, when a fellow across the pond named Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a swashbuckling English soldier obsessed with New World colonization, was granted a charter to the newly dubbed Province of Maine, between the Merrimack and Kennebec rivers. Some early historians place the first colonists at the mouth of the York River around that time (it was then the Agamenticus River), but more likely they straggled in over the coming decades. By 1642, there were enough folks around that Gorges chartered a city and called it Gorgeana. Ten years later, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony annexed Maine, Gorgeana reincorporated as York. After Kittery, it’s Maine’s second-oldest incorporated town.

That’s a lot of history, and in 1896, the Old York Historical and Improvement Society formed to preserve it. In 1984, it combined with two other orgs, stewards of local landmarks, and OYHS was born. But as executive director Joel Lefever explains, not every item in the combined collection had a particularly strong tie to the area. The various predecessor groups were sometimes more focused on filling out a historic home, for example, than with any given item’s provenance. “So they needed lots of domestic furniture from different periods that we just didn’t have — for instance, there were a bunch of 1850s furnishings, but from a Connecticut family,” Lefever says. “They were buying antiques from a Massachusetts antiques dealer, and none of those things had anything to do with York.”

Since Lefever came on board, 10 years ago, OYHS has deaccessioned a number of pieces that had little or no local connection, and in the last couple of years, it has augmented the collection with a few real treasures that do. Among them is a gracefully swooping, 18th-century bombé secretary bookcase, procured last year from descendants of Piscataqua pioneer and merchant prince William Pepperrell. This summer, OYHS acquired a striking 17th-century chest of drawers, a rare surviving example of a piece by a storied Boston cabinet shop and one of just a few surviving objects known to have been owned by York residents in the 1600s. The Remick Gallery, in OYHS’s Museum Center, displays these, along with other exquisite brown furniture and some left-field items that help tell the story of settlement-era southern Maine: a stave-and-hoop communion tankard from Maine’s oldest church congregation, wood from an apple tree planted in the 1630s, a set of astoundingly detailed 18th-century embroidered bed hangings, and more.

HIGH FIDELITY

Visitors to York’s Old Gaol a decade ago wandered through rooms set up with period artifacts to look like colonial living rooms or kitchens — and, well, a bit less like a jail. Today, OYHS takes a more spartan interpretive approach to the ancient lockup, which has a 300-year-old stone-and-timber collection of cells at its core, expanded over the years with additions and a striking gambrel roof. Highlights include panels telling stories, drawn from court records, of those who found themselves guests (crimes include murder, embezzlement, and kissing), as well as a small display of fascinating items that Lefever found in 2018, crawling on his stomach into a portion of the building’s eaves. Among the relics he pulled out are old cobbling tools (prisoners were presumably sentenced to shoemaking) and preserved corn cobs, lobster claws, and deer mandibles (dinner menus seem to have been surf and turf).

The setup at the Old Gaol reflects an interpretive philosophy that stresses fidelity to how a site likely looked in its heyday. During the pandemic downtime in 2020, that approach reshaped the freshly renovated Perkins House Museum, a many-gabled manor overlooking the York River. From 1898 until 1952, it was the summer home of the well-to-do Perkins family, prominent among the aristocrats and artists who were drawn to York in the Gilded Age. (The writer who coined that term, Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, sometimes dropped by to use the Perkins’s phone while summering across the river.)

Mary Perkins and her daughter, Elizabeth, furbished their home in a Colonial Revival style and filled it with bric-a-brac from their world travels. Both were champions of historic preservation, and when Elizabeth died, in 1952, she bequeathed the home and its contents to an OYHS predecessor. While COVID kept visitors out, Lefever and his staff used historic photos and inventories, servants’ manifests, and more to restore the rooms to how they appeared in 1951, during Elizabeth’s last visit, right down to the placement of the decorative plates on the mantle and stacks of vintage magazines on the tea table. Guided walks through the Perkins House, offered Friday afternoons through October, feel less like touring a stuffy museum and more like dropping into an opulent post-war Airbnb, with the host simply out for the weekend. “The house now has much more of the personality of the ladies who lived there,” Lefever says.

MARSHALL PLANS

One of the more photogenic buildings under OYHS’s care, a circa 1867 dry-goods store at the edge of the York River, isn’t a historic-tour site but instead the George Marshall Store Gallery, a lauded bastion of contemporary art. After the gallery’s longtime curator, Mary Harding, retired in 2020, York native Kate Rasche took over as director last summer, with plans to continue the contemporary focus but invite more guest curators, highlight more emerging and mid-career artists, and use the space for programming beyond visual arts. Visitors through mid-September can catch a plein-air show curated by Saco artist Charles Thompson, featuring artists that include Lois Dodd and John David O’Shaughnessy. Starting in October, the curator of Massachusetts’s Fitchburg Art Museum juries an open-call show of artists from across New England.

HISTORICAL HOMECOMING

In June, OYHS announced the purchase of a 15,000-square-foot church in York, a few miles from the Museum Center, that will house its full collection and paper archives, as well as a public reading room, beginning next year. The purchase ends a period of iteranancy for the organization’s holdings. Since 2014, its collections have been stored at a facility in adjacent Kittery. The archives and rare collections joined them there in 2019, after years of piecemeal storage across OYHS’s various museum houses and outbuildings. That move prompted grumblings by some York dwellers who didn’t like the idea of their town memorabilia ensconced with their neighbor (and, in some ways, rival — among other things, the two towns have been squabbling for years over the shape and placement of their border). That fall, one committed local historian set up a daily protest vigil that lasted well into the winter.

But bringing the collection back to York — and into a larger space — is more than just symbolic, Lefever explains, especially as the organization aims to further refine and expand its collection. “Too many museums are forced to kind of put things in basements and attics,” he says, “and you just can’t really maintain things very well when you’re doing that.”

It’s also difficult to research and reorganize, Lefever says, which will soon be critical as the Emerson-Wilcox House is repaired and its interior spaces reimagined. He hopes to install a new maritime exhibit there, drawing on items — ship paintings, elaborate nautical charts, the elegant furniture and other household goods of seafaring merchant families — that, in some cases, have spent decades relegated to storage. It’s an indication, he says, of just how many more stories OYHS has to tell, how much Old York history remains to be explored. He invokes a memory of a grad-school colleague from Virginia, where American colonial history arguably began, at Jamestown. “She used to say, ‘You can’t spit in Virginia without hitting history,’” Lefever remembers. “Well, it’s the same way here.”