By Brian Kevin

From our April 2022 issue

If you don’t instantly associate Maine with gem and mineral mining, you might be forgiven, but it probably means you haven’t spent much time in Oxford County, where scratching away at the state’s western mountains and foothills has been a way of life for generations. The original Oxford County rock hounds were a pair of college students hiking across a ledge on Mount Mica, in the town of Paris, in 1821. “As they were enjoying their jaunt, a sparkling light at the base of an overturned tree caught their attention,” Jane Perham writes in her exhaustive 1987 history Maine’s Treasure Chest: Gems and Minerals of Oxford County. “A search of the tree roots revealed a beautiful green stone shaped like a prism.”

The stone was the rare mineral tourmaline, one of the world’s most colorful and varied gems and, today, Maine’s official state mineral. It’s found in comparative plenty around Oxford County (and in patches elsewhere around the state) because of the abundance of an igneous rock called pegmatite, a coarse-grained granite that tends to house uncommon and eye-catching minerals like beryls, topazes, garnets, rose and smoky quartzes, tourmalines, and more. In the wake of the Mount Mica find, treasure hunters and upstart mining concerns took to the surrounding hills looking for all of these, and along the way, they realized the potential for commercial minerals like mica, valuable for its heat resistance, and feldspar, used to make porcelain products. From the mid–19th century to around the time of the Depression, Oxford County’s mineral resources were part of western Maine’s economic backbone.

But by 1972, as veteran Maine miner and gem cutter Phil McCrillis explains, mining and gem hunting in the area had long since become a niche pastime. “There had been a definite lull,” says McCrillis, who sits on the advisory board for Bethel’s Maine Mineral & Gem Museum. “We were the TV generation, I guess. It was mostly just the old-timers doing it, scratching around at abandoned localities, nobody really doing anything mining-wise. It was a very small community where everybody knew everybody, with a bunch of tiny rock shops here and there.”

McCrillis’s dad owned one of them, called Yankee Gems, in Roxbury. Dean McCrillis was a teacher by trade but known in the area for his mineral expertise. One day, in August 1971, a trio of excited amateur rock hounds stopped by the store to get his assessment of some tourmaline they’d found chipping with hand tools at an abandoned mine on Newry’s Plumbago Mountain. McCrillis’s father accompanied them to the site, known as the Dunton Quarry, and came away impressed. “It was all secret squirrel, because they didn’t have a lease then,” McCrillis remembers. “The spot was on paper-company-owned property, so my father said, ‘We’ve got to shut up about this while we negotiate a lease with International Paper.’ They didn’t know the extent of it at that time.”

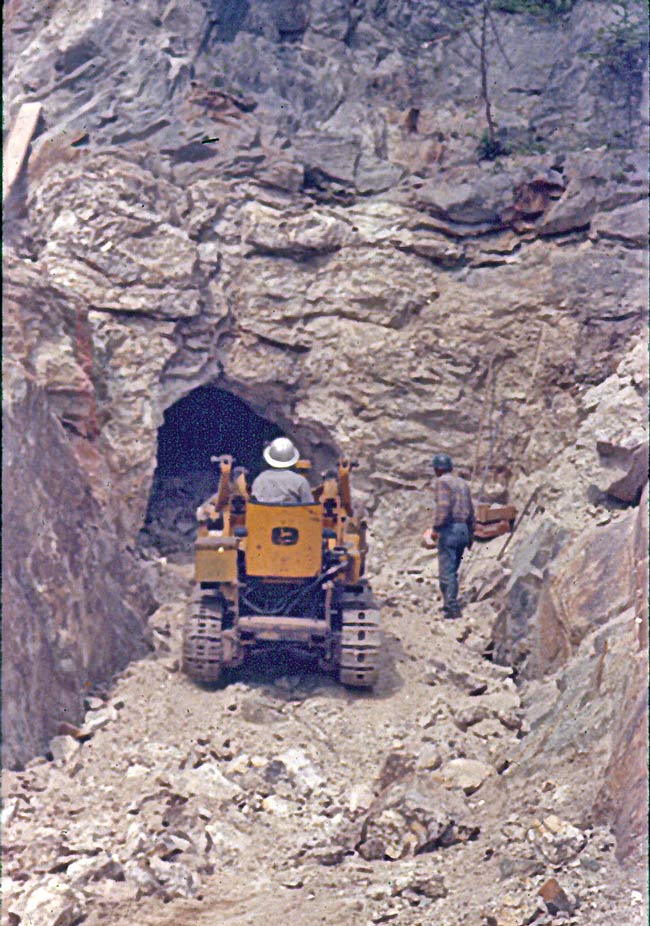

Over a year later, with a lease in hand and incorporated as Plumbago Mining Corporation, Dean McCrillis and two of the original discoverers returned to the site with heavy equipment, explosives, and a veteran local miner named Frank Perham. Over several weeks in October, they began drilling and blasting, uncovering one astonishing pocket after another of gem-quality tourmaline, crystals that ranged from small to impressive to enormous, and in a rainbow of colors. The partners, with the help of a few friends and family members, pulled a child’s red wagon up and down a ramp to haul out material, dozens of pounds at a time. The month culminated in the discovery of what the partners could only call “the Big Pocket,” a cavernous room chock-full of watermelon-colored tourmaline crystals, a grotto like none of the veteran rock hounds on the site could have imagined.

“I mean, things like that just don’t happen — the enormity of it,” recalls Jane Perham, who visited the site where her brother, Frank, labored under the rock. “Often, you find a pocket that might be two feet by two feet, filled with mud and some nice crystals. But honest to god, the Big Pocket up there, you could have put my mother’s Cadillac in it and parked it nicely. It was the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen.”

As word of the Newry find spread, the Plumbago partners fielded calls and visits from the state geologist, Harvard University, the Smithsonian, and more. They leased a bank vault in Rumford and an office above it to start the yearslong task of sorting, grading, and selling the spoils. Ralph Pride, the owner of Portland’s Cross Jewelers, was a 23-year-old learning the family business when he visited the Plumbago partners the following year.

“What I saw on my first visit simply blew me away,” Pride recalls. “I mean, the quantity of gems! And everything was just astonishingly beautiful. They found two metric tons of gems — you don’t typically measure gems in tonnage. It was the largest gem find in North America. . . . The quantity of what they found was so vast, we have cutters who still have material a half century later and are still cutting gems.”

Author and petrologist Karen L. Webber, who wrote a biography of Frank Perham, estimates the contemporary value of tourmaline from the Dunton Quarry’s two largest pockets at $50 million. More modest discoveries continued into 1973 and 1974. By 1975, McCrillis recalls, the mining was mostly finished, but with so much potential treasure buried in the miners’ dump sites, he spent the summer camped there in a converted school bus, charging a small admission and keeping an eye on the safety of gem hunters.

Rock hounding and gem mining in western Maine saw a resurgence in the wake of “the Big Find.” The Maine Mineral & Gem Museum, in an exhibit dedicated to its aftermath, reports that at least 40 dormant quarries have reopened in the decades since, many in the years immediately following. Some have made significant discoveries — and not always of tourmaline. In 1989, miners in nearby Buckfield discovered one of the world’s largest morganite crystals, a 52-pound specimen of the pinkish beryl, nicknamed the “Rose of Maine.” The current owners of the Dunton Quarry made headlines last year for discovering, on another face of Plumbago, a lithium deposit that could be valued at as much as $1.5 billion (if it could ever be mined, which the state’s metallic-mining laws likely prevent).

“The Newry find just got everybody’s juices flowing again about finding treasure,” McCrillis says. If it hadn’t happened, he doubts there’d be a mining museum in Bethel today. “We had found something that was a once-in-a-hundred-lifetimes kind of thing. It was an old locale, and now people had new technology and thought, ‘Well, they did it at an old mine, so we’re going to do it too.’ It really gave a boost to the rock-hounding community and brought in some new blood.”

It also raised tourmaline’s profile on the gem market, Pride explains. “Most people couldn’t even pronounce the word tourmaline,” he says. “Every once in a while, they’d find a little bit here, a little bit there, but nothing to get really excited about. So it really wasn’t on jewelers’ radars or on the general public’s much. Then, the 1972 find broke open the floodgates.”

But it also did more than that, Pride suggests — it brought the thrill of potential discovery back to Oxford County and the western Maine mountains. He remembers reading about the Dunton Quarry for the first time in the spring of ’73 and feeling the same heart-tightening flicker of excitement and wonder he’d felt as a boy, reading about the serendipitous 1821 discovery on Mount Mica. “Now, for anybody who goes for a hike in the woods,” Cross says, “there’s this additional sense of consciousness and awareness that they too, like the two kids above Paris Hill, might see crystals glimmering on the roots of an upturned tree.”