By Jesse Ellison

Photographed by Michael D. Wilson

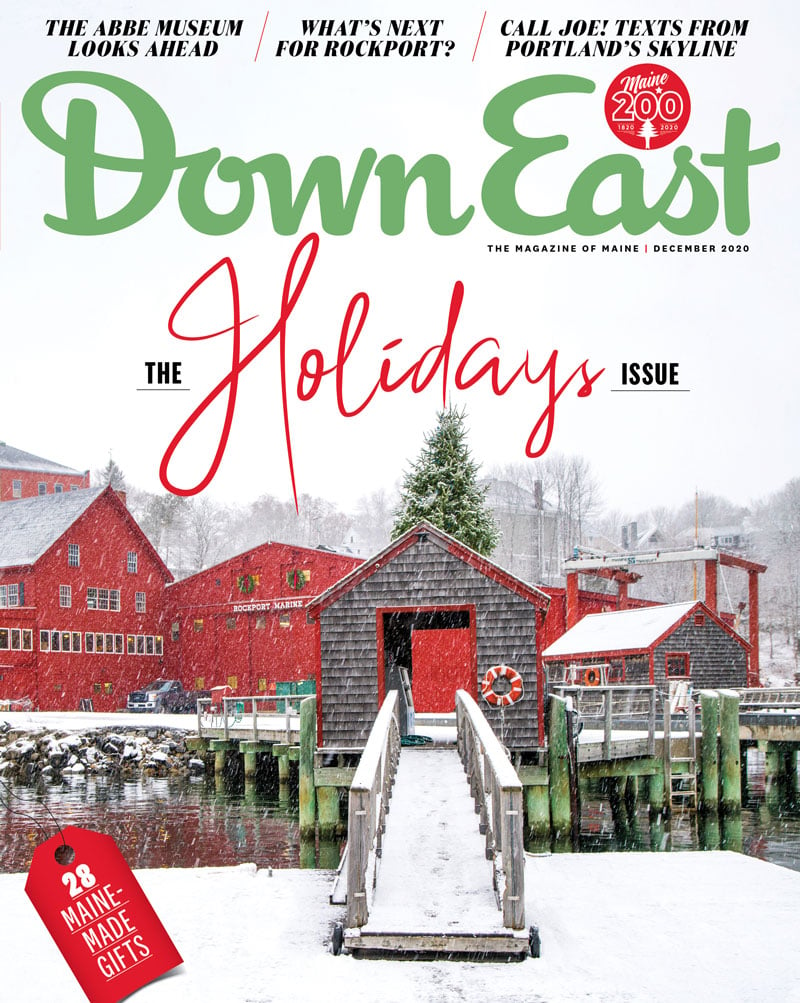

From our December 2020 issuehttps://downeast.com/issues/december-2020/

As a kid growing up in Motahkmikuhk, or Indian Township, a Passamaquoddy reservation of fewer than 1,000 people in eastern Washington County, Chris Newell felt downright giddy about visits to Mount Desert Island. The island has had a Passamaquoddy presence for more than 12,000 years, a legacy celebrated occasionally at festivals and events sponsored by Bar Harbor’s College of the Atlantic or the Abbe Museum, which was then a small, privately run exhibit space inside Acadia National Park, dedicated to the history and culture of Maine’s Native people. Newell’s father, Wayne Newell, a much-respected Passamaquoddy musician and educator, would sometimes be invited to speak and perform, and Newell liked nothing more than when his dad would bring the family along.

“Acadia National Park, Cadillac Mountain, Thunder Hole — it was the most awesome place in the world,” Newell says. “This was Disneyland.”

But the Abbe itself was a different story. Housed in an Italianate, chapel-like building at the park’s Sieur de Monts Spring, the Abbe’s exhibits revolved around pieces amassed by its founder, Dr. Robert Abbe, a pioneering New York doctor and Bar Harbor summer person who collected stone tools, pottery shards, and other artifacts and who died just before the museum opened in 1928. The items were centuries old and encased in glass, presented as remnants of a vanishing culture.

In 2018, the Abbe Museum became the state’s first Smithsonan Affiliate, and it’s still the only museum in Maine to forge such a partnership with the world’s largest museum and research complex.

“Even though it had an ethnographic collection of Wabanaki items on display, it never actually felt like Wabanaki space — it felt like somebody else’s space,” Newell recalls. “I recognized, even as a child, that they’re forgetting that we have a living community. I lived in one, and here, I’m seeing only things that were hundreds of years old. It didn’t make any sense.”

Newell, who is 46, recalls his early impressions of the Abbe while sitting on the back patio of what is now its main campus, in downtown Bar Harbor, a 17,000-square-foot former YMCA that the museum opened in 2001. Last winter, Newell took over as the Abbe’s new executive director and senior partner to the Wabanaki Nations. He is the institution’s first Wabanaki executive director in its nearly hundred-year history, and his hire marks a watershed moment in a decades-long effort to privilege Wabanaki voices at the museum. In a sense, though, it couldn’t have come at a worse time.

As Newell chats on the patio, wearing a surgical mask and a pale-blue button-down, his long dark hair pulled back in a low ponytail, the museum behind him sits dark, closed to visitors on account of the pandemic, as it has been since his second week on the job. He has visited the building infrequently enough that, this morning, he struggled with his keys trying to unlock the back door and, once inside, had trouble finding the light switches.

It is an understatement to say that this year has been a challenging (and, arguably, unlucky) time to take over leadership of a cultural institution in a town reliant on tourists. And yet, Newell seems almost to be pinching himself.

“I keep looking at where we’re at, and, you know, as crazy as this year has been, I’ve honestly been given the best gift in the world,” he says. “I get to come to this particular museum, in this place that I have such a long history of love for, and I get to do what I love and make a living wage at it. Ten years ago, I never would have imagined I would be in this spot.”

Newell’s hometown is 90 miles and a world away from Bar Harbor. His was the first generation on the reservation to grow up with access to running water and electricity, which meant they were also the first to have television and radio. His mother, who is white, drove the school bus and was the school secretary. His father is something of a legend in the Wabanaki community. Legally blind since birth, Wayne, now 78, holds a master’s degree in education from Harvard, and he’s a storyteller, singer, and driving force behind the effort to preserve Wabanaki languages, having written 40 books in Passamaquoddy, including the language’s first dictionary.

Newell, by contrast, was drawn to science and math growing up, and when he left Washington County for Dartmouth College in 1992, he had aspirations to become an engineer. It was at Dartmouth that Newell discovered the erasure he’d felt at the Abbe Museum existed in the broader world as well. Most of the other Native kids on campus were from Western tribes and had never heard of the Wabanaki people or the four tribes they comprise. Fair skinned, with pale-blue eyes, he was sometimes met with disbelief when he said he was Native. During his first semester, he went to a football game and was stunned to see his fellow students don “war paint,” make tomahawk gestures, and shout chants about scalping — all in homage to a former mascot retired in the ’70s.

But there was also a vibrant and engaged Native community on campus. Newell joined a powwow drumming group and, in his second year, took a music elective that he credits with changing his life, one that included a performance by Tuvan throat singers from Mongolia and Siberia.

“Literally, watching them perform live in our class, seeing that immense amount of talent, changed the way I thought about myself and my culture in an instant,” he says. The performance reminded him of a Passamaquoddy belief that music has a magical power: the ability to confer energy. It made him think about his father.

“I thought, ‘Holy cow, I grew up with someone that taught music and has done this to other people, making them dance, making them happy — I’ve grown up with that,’” Newell says. “I realized I had that same power in me if I chose to expand on it.”

Newell changed his major to Native American Studies and became the lead singer of his drumming group, performing at campus events, then all around New England. He was introduced to the Mystic River Singers, an intertribal drum group based in Connecticut, and started performing with them. After his junior year at Dartmouth, he dropped out, had his first child, and moved to Connecticut, where he got a job working construction, singing with the Mystic River Singers on the side.

For most of the next two decades, music was central to Newell’s life. With Mystic River, which became one of the best-known powwow groups in the country, he traveled all over the U.S. and Canada and as far as Hong Kong, performing at powwows and other events. It afforded him time with people from a number of different tribes. “At those events, a lot of education happens,” he says. “You get to see how elders speak to their own community and also how they speak to outsiders, how they teach about their culture. I really started to pay attention — to just sit there and shut up, to listen and watch those elders teach.”

When he was in his late 30s, with a wife and a growing family, Newell decided he needed to finish his degree and find a more traditional career. Eighteen years after leaving Dartmouth, he enrolled in community college and then, two years later, transferred to the University of Connecticut. He paid the bills working the smoky slot-machine floors at Connecticut’s Mohegan Sun casino, while attending classes and continuing to sing on the side.

Then, in 2013, he applied for a job as a museum educator at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, the world’s largest Native American museum, located on tribal land outside Norwich. “I billed myself as a lifelong educator,” Newell says. “When you’re Native in this world, when you’re Passamaquoddy and you leave your homeland, you are constantly educating everybody about your existence.”

He turned out to have both a knack and a passion for the work. Newell’s wife, Kristen, is Mashantucket Pequot, and their three children are enrolled in the tribe. “This is their history,” he says. “I don’t want them growing up in a world where they have to have that chip on their shoulder because they’re constantly having to educate everybody and prove to the world that they exist.”

Day after day, he watched kids and adults lighting up with new knowledge of Native history.

“Really, there are these bright eyes, this enlightenment that happens. It’s beautiful. It’s addictive how beautiful it is,” Newell says. “I was pissed off as a young man. It was a great avenue for me to get all of that anxiety and stress and put it into something positive.”

In 2016, the Abbe Museum installed its new core exhibit, People of the First Light, “affirming that there are Native people in Maine and the wider Wabanaki homeland today.” The exhibit marked a shift from the museum’s approach during Newell’s youth. Before the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the Abbe, like most museums of its kind, held human remains and funerary objects. “Native people of my father’s generation wouldn’t even walk into a colonial museum,” Newell says. “They seriously were scared of these places because they held our bloodline ancestors within the building.” More recently, the museum has repatriated more than 900 additional funerary objects not associated with human remains.

Work at the Pequot, a nonprofit museum owned by the tribe, was not lucrative, and with four kids to support, Newell struggled to make ends meet. But he loved the job and moved up quickly. When the museum hired Jason Mancini, one of Newell’s UConn professors, as its executive director, Mancini asked him to lead the education program.

“What always struck me from the time I first knew Chris were the ways in which he could take a difficult issue and engage in a contemplative way, but also in a way that didn’t scare people away,” Mancini says. “People outside of this cultural context can sometimes be fearful about saying the wrong thing, about being offensive. Chris prefaces his conversations with openness. Because of that sensibility, he could talk to a range of audiences — from kids to college professors — in a way that would connect to where they were.”

His work at the Pequot also showed Newell firsthand how many people wanted to better engage Native history and dismantle their own ethnocentrism. He watched teachers scrawling notes as he spoke, incorporating his teachings into worksheets and lesson plans. When the museum faced financial hurdles and had to shut down part of the year, he and Mancini joined forces (together with their Pequot colleague endawnis Spears) to cofound an organization called the Akomawt Educational Initiative. Akomawt is the Passamaquoddy word for a snowshoe path, the symbol that drives their mission: it’s a path that becomes easier to travel the more it’s used. Akomawt has consulted with colleges and universities around Connecticut and with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where the organization helped facilitate the city’s first Indigenous Peoples Day.

Last year, the Abbe announced it was seeking an executive director and senior partner to Wabanaki Nations. That title reflects a process, launched under the leadership of Newell’s predecessor, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, to decolonize the Abbe as an institution.

“Museums house the spoils of colonization,” explains Catlin-Legutko, now the director of the Illinois State Museum. “They are, by nature, extractive. Decolonizing means developing practices to undo that harm.” Catlin-Legutko bought copies of a text called Decolonizing Museums for the entire board. It became a blueprint for their work and for the museum’s new strategic plan, which defines decolonization as, “at a minimum, sharing authority for the documentation and interpretation of Native culture.”

During the last decade, Abbe leadership has appointed an advisory council made up of tribal members, brought in Wabanaki leaders to examine their collections, turned over exhibitions to Wabanaki curators, and dismantled the museum’s board of directors to ensure at least half its members are Wabanaki. The author of Decolonizing Museums, Amy Lonetree, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and University of California history professor, says the Abbe was the country’s first non–tribally owned museum to take on the decolonization mission so proactively and comprehensively — and it is still one of the few.

“Honestly, when the job opening came out, I didn’t even look at it,” Newell says. With only a bachelor’s degree, he figured he wasn’t qualified. Then he started hearing from colleagues and members of the Passamaquoddy and larger Wabanaki communities, nudging him to apply. “I finally read the job description and was like, ‘Holy crap, this is perfect for me. I’m doing this already, and I could do it at home. I could come back and do it for my own people.”

Board chair Margo Lukens, who is white, says that hiring Newell was a clear opportunity to “put our money where our mouth is,” where decolonization is concerned. What’s more, she says, Newell “came spring-loaded for the work.” He started the job on March 2.

Two weeks later, the museum, along with virtually the entire state of Maine and much of the country, shut its doors.

Nonetheless, Lukens says, the Abbe “is in a very, very happy place” right now — thanks largely to Newell’s leadership during a year of unprecedented, on-the-fly reinvention.

In May, for example, the museum was slated to host its annual Indian Market, an event that ordinarily attracts some 5,000 people. Newell and his six-person staff canceled the in-person market and moved the whole thing online — figuring out in a matter of weeks how to stream a six-hour day of live content. The event earned them a favorable nod from the New York Times and, in November, an award from the New England Museum Association, presented to the museum’s entire staff.

It’s been a trying year, Newell acknowledges. He’s living back in Maine for the first time in decades, but the pandemic shutdown has kept him from experiencing much of home. His father is fighting cancer, and he hasn’t been able to visit his parents since taking the job. Still, he’s proud that the Abbe has managed to carry on. The museum retained its entire staff, and though it has lost substantial admission revenue, keeping the museum shuttered (while many Maine museums reopened, with restrictions, late in the season) has kept overhead costs down. Plus, Newell says, moving programming online has enabled people from all over the world to attend not just the Indian Market, but lectures and other programming. Events that might have brought 20 people to the museum now might attract 100 online attendees, from places as far away as Hawaii, the Philippines, and Ireland. It’s a new level of engagement and one reason that Newell feels the Abbe’s post-COVID future is bright.

“The year 2020 has been a disaster for the world,” he says. “It’s been a disaster for the museum in a lot of ways as well. But at the same time, it’s been amazing. The sky is the limit, is what I feel like right now. That’s a hell of a feeling to have when, a couple of years ago, it was a struggle to pay for socks. A lot of ancestors are really looking out for me.”