By Brian Kevin

From our September 2022 issue

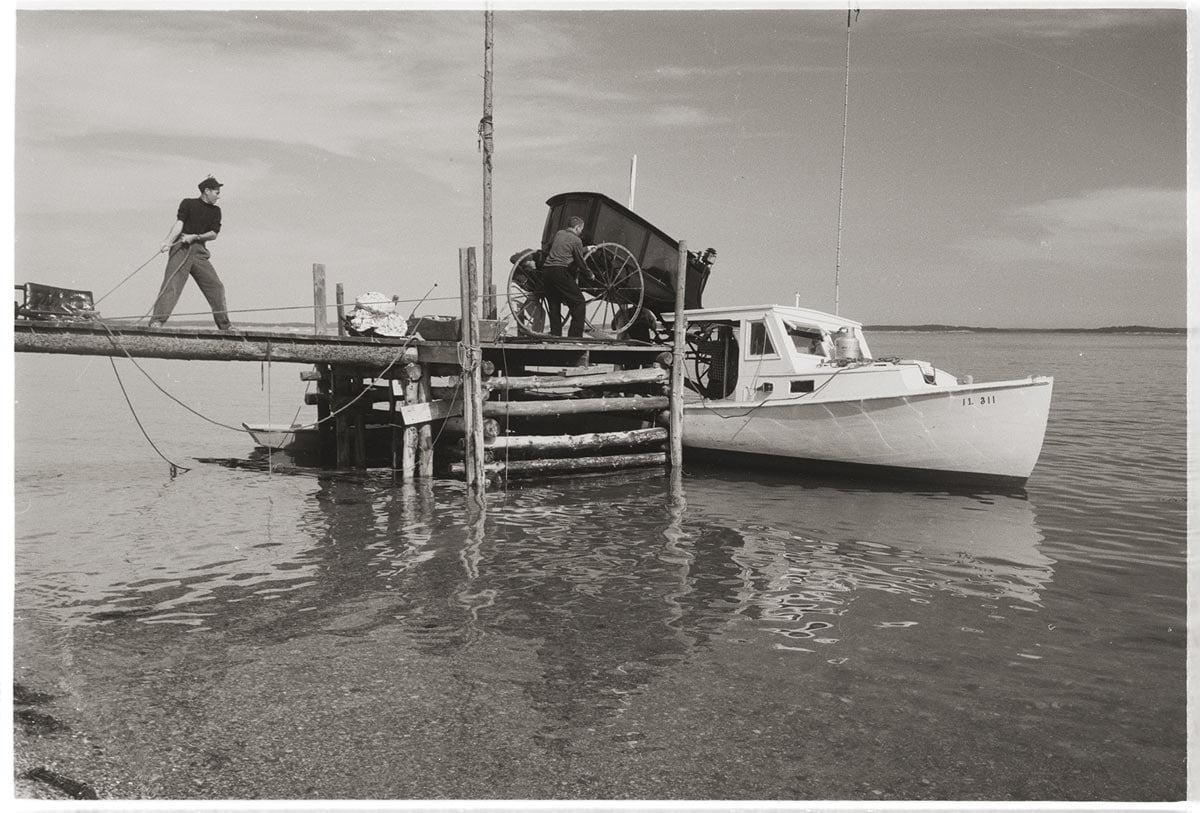

There may be no one photographer who captured post-war, small-town New England as prolifically as Kosti Ruohomaa. Raised in a Rockland farming family by Finnish immigrant parents, he embraced photography as a young man, along with painting and illustration, and launched a creative career that made him a mainstay in the 1940s and ’50s in the pages of influential magazines like LIFE, Look, Time, and National Geographic (along with an upstart regional called Down East). When he died in 1961, at just 47 years old, he was a hotshot in the photo world, known mostly for capturing vivid scenes in the rural corners of his home state. Then, in the decades to come, outside his home turf of the midcoast, he faded into relative obscurity.

A 2022 exhibit at the Penobscot Marine Museum, Kosti Ruohomaa: The Maine Assignments, was originally scheduled for 2020, to coincide with the state’s bicentennial. The museum had acquired Ruohomaa’s archive three years before: eight banker’s boxes filled with more than 50,000 slides, which photo archivist Kevin Johnson hauled up to Searsport from a warehouse in New Jersey. They’d been stashed there years before by a storied New York photo agency called Black Star, which represented Ruohomaa for the bulk of his career and agreed to donate the trove at the request of Johnson and Deanna Bonner-Ganter, a former Maine State Museum curator and Ruohomaa’s biographer. Five years later, PMM archivists are nearly halfway through digitizing the prodigious collection.

The Maine Assignments highlighted not only Ruohomaa’s output but also his process, with huge interpretive panels displaying iconic images alongside outtakes, strips of negatives, correspondence with photo editors, and more. We caught up with Johnson and digital collections curator Matt Wheeler to hear about how the show came together — and why Ruohomaa’s work stands the test of time.

How does the collection of tens of thousands of Kosti Ruohomaa’s images fit in with the rest of the collections of the Penobscot Marine Museum?

Matt Wheeler: It’s intimately tied to the museum’s mission, because the guy grew up looking at Penobscot Bay and had this lifelong love of the area and of Maine traditions. At the same time, of course, he worked for this very cosmopolitan agency in New York City and traveled the country, but his photos always seem to reflect a similar sensibility about tradition and hard work and rugged settings, about ordinary people and folks who are a little rough around the edges. And yet he was also friends with Andrew Wyeth and all these other artists. And he ended up leaving his family farm, to his father’s dismay, because wanted to study art and literature.

That tension — between worldly and provincial — seems to be at the heart of Ruohomaa’s life and work.

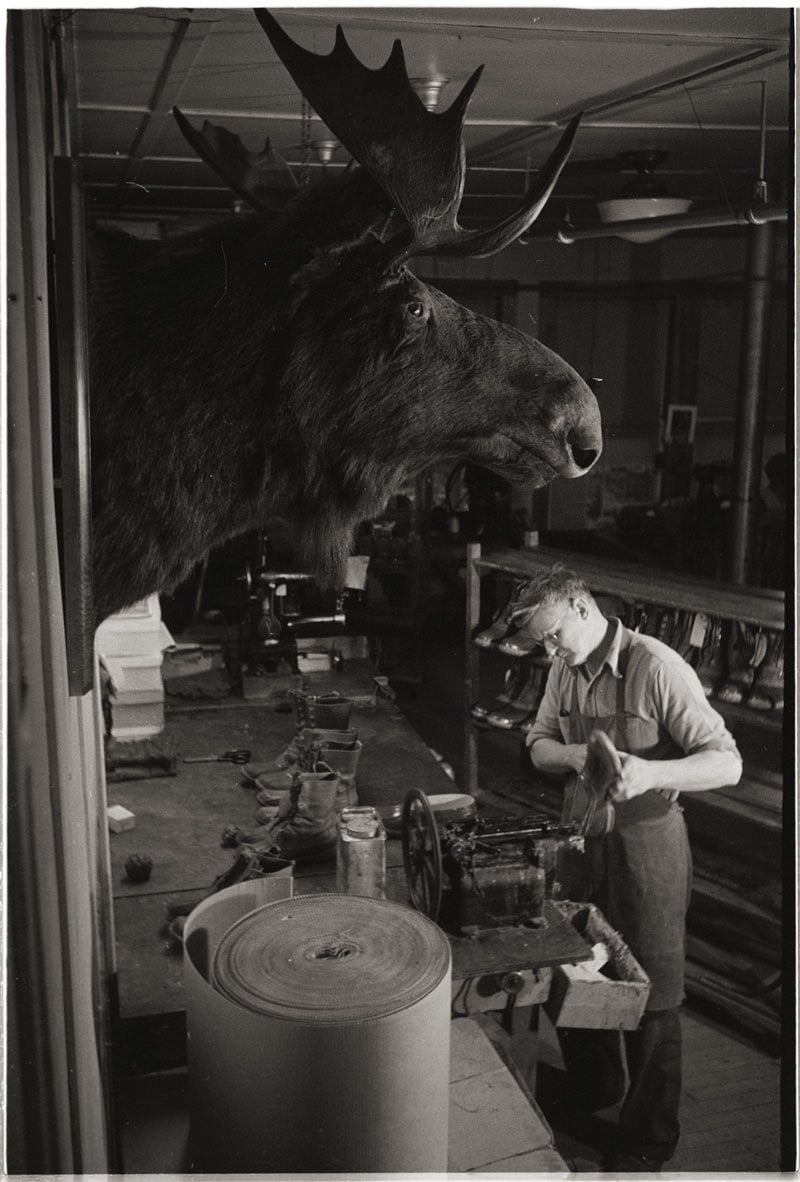

Kevin Johnson: Yeah, you know, he did go to a one-room schoolhouse. He did work on a farm. He milked the cows at 5 a.m. and harvested blueberries. And the people that his family associated with, they were stonecutters, they were fishermen, they were herring mongers — all these different traditional roles up here. But then he got hired to go out to California and be an animator for Disney — he’d been in art school for one year, then got this gig out there — and I’m sure that just broadened his view of the world. Then he gets this job for LIFE magazine where he’s jet-setting around. His first assignment becomes a LIFE magazine cover. So, you know, he has money in his pocket, he’s wearing good clothes, he’s getting to do these things. But he comes back, and the story that he wants to tell is what he lived. I think he had the sense that, hey, people don’t know about this. And he was acutely aware that that world was changing, that technology was moving fast, and that people were not going to be doing these jobs that he grew up observing.

What would you say characterizes a Kosti Ruohomaa photo?

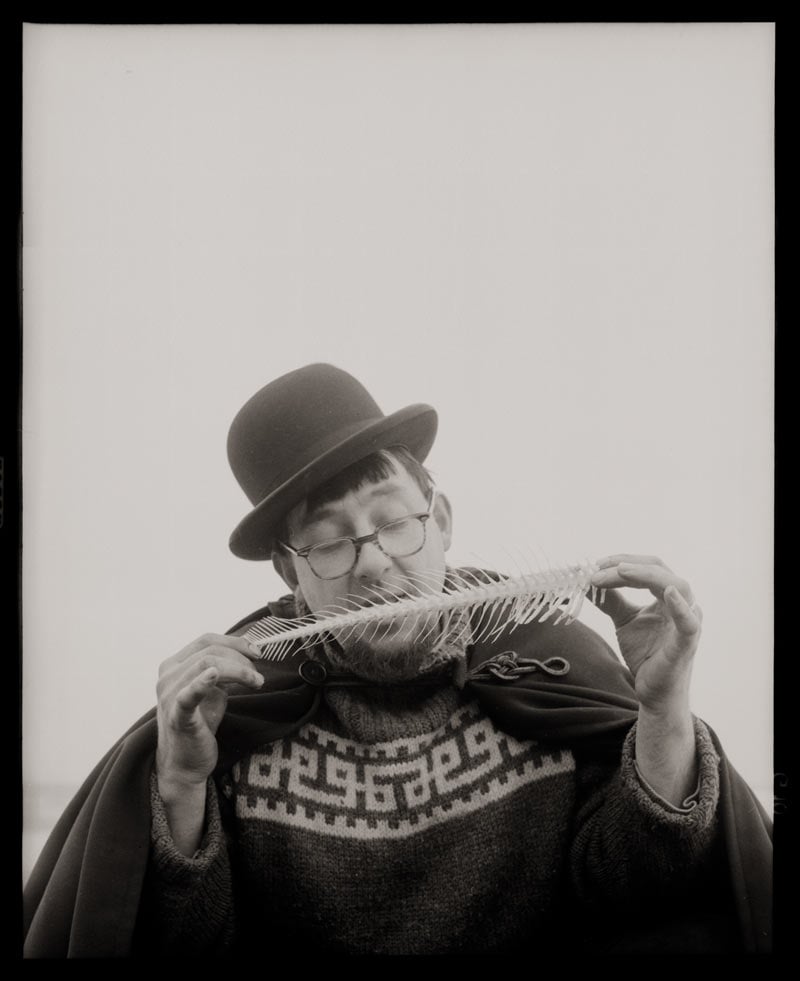

Wheeler: A lot of the photography in our collections — though certainly not all of it — I might describe as kind of prosaic: somebody is trying to produce a visual document of something. But Kosti, he had a kind of lyrical or poetic way of seeing things. He had this wonderful eye for geometry and contrast and tonality that made his images dramatic, arresting, sometimes mysterious.

Johnson: Even if it was what you might think of as a mundane job or subject, he injected a life into it through his skill with the camera. I think he really liked people — characters, you know? Sometimes unusual-looking people. It’s just great, the faces that he picks out of a crowd. And it’s obvious that he connected with the people he was photographing.

How do you suppose he forged that connection?

Johnson: Well, part of it is that he used a medium-format camera, primarily, which he’d have held at his waist — so he’s looking down at it, where he can be talking to people and just clicking that shutter when he sees what he wants.

Wheeler: When you have a camera at your face, it’s like it’s interposed between you and the subject. People get self-conscious.

Johnson: But the other thing was he just had this true passion for all things New England and Yankee. He wanted to introduce it to the world, and he really did. Because if you think about LIFE and Look and magazines like them at that time, you know, they were Facebook before there was Facebook. They gave people, say, their first views of what it’s like in Maine in winter or what it means to catch a lobster on Monhegan island. They know that from his photos. I mean, he was the one who was introducing these faraway places and people.

Wheeler: And I’m guessing those kinds of people were his childhood heroes. They were who he saw when he was an adolescent growing up in Maine. He was impressed by it, and it stayed with him.

So would you call Ruohomaa a photojournalist? A fine-art photographer? Something else?

Johnson: Well, he was not a news photographer, and he wasn’t covering news stories, for the most part. He was a photo essayist. I would say that’s the best way that you can describe his work, and it’s why we approached this exhibit the way we did. We didn’t want to have just single photos from these Maine assignments in frames on the wall, because single photos just don’t tell the stories. And that’s not how he shot it, you know? We wanted it to come across like images on a photo editor’s desk — these are the pieces they’d have been working with to come up with a four-page piece in LIFE or Look. We wanted to show not just photos but also his contact sheets and his wax pencil mark showing where to crop. Those are the kinds of things that are really exciting for us to find because we just get to see how his eyes worked. And then we also wanted to point out the ways that he composes photos, to point out some of these things that make these photos strong for people who, you know, may think, “I love this photo. But why do I love this photo?”

So Kosti, he wants to tell a story through a series of photos. And it can’t just be about the people involved. It can’t just be what they’re doing. It can’t just be the setting. It has to be the combination of the three.

Wheeler: I think one difference, maybe, is that photojournalism is all about the moment and capturing what’s contemporary, where photo essays are just maybe a little more timeless. That’s definitely one of the things that characterizes the work he was doing. Obviously, they’re dated now, and in certain ways, there’s a nostalgia to them. But at the same time, they’re not about news events. He was looking at people and the work they do or at how people gather and celebrate together, this kind of thing.

Johnson: We also wanted to show that he was not interested in the prettiness of Maine. He wrote a letter not long after a National Geographic issue that he had, like, a 20-page spread in, on the opening day of lobster season, shot in 1958. It’s about Monhegan, and he says, “In the summer, it is a bit too idealistically beautiful; in the winter, it has guts and drama and doesn’t wear such a pretty surface. Anyway, it has the kind of meat my camera likes.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.