By Jaed Coffin

Photographed by Jason Frank

From our October 2021 issue

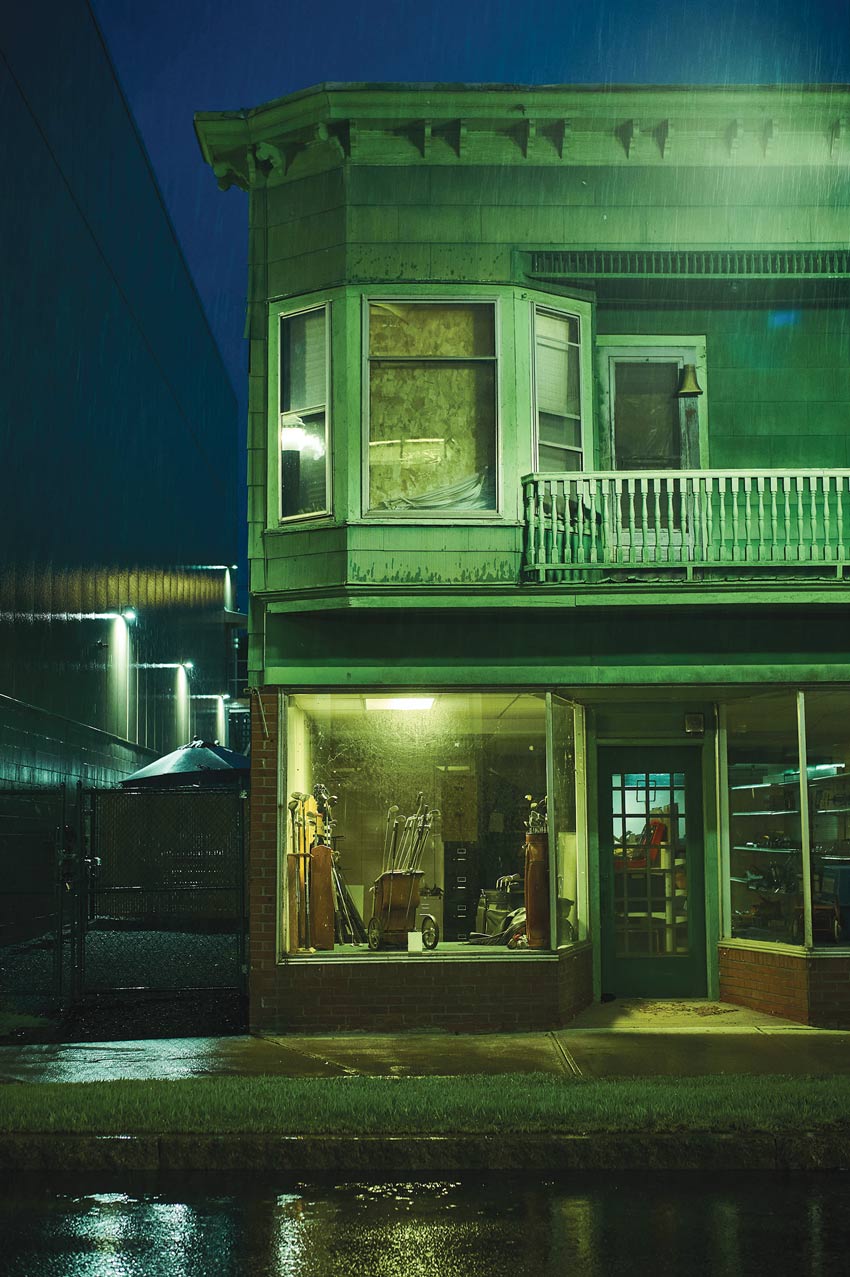

Marcel Morin, the 75-year-old owner of Pine Tree Trading Company, sat in a rocking chair surrounded by empty shelves and packed boxes and explained how he felt that pawnshops are often misunderstood, as seedy marketplaces for items of dubious provenance. Ever since he opened his shop on Lewiston’s Lisbon Street, in 1988, he said, his chief role had been as banker to those too poor to do business with banks — “Most of my customers needed $20 or $10 or $50 to get them through the month, to keep the lights on, to buy diapers.”

Customers brought an item as collateral. He offered a loan based on the value, to be paid back at a state-capped interest rate of 25 percent every 30 days. If they didn’t make the payments, the item could be sold, although Morin admits to sometimes renegotiating loan terms, trying to cut people a break. The ubiquitous pawnshop symbol — three golden spheres hanging from a rod — traces to the Italian Renaissance, and though the precise significance is foggy, it always brought to mind for Morin the three-to-one likelihood that the owner of an item wouldn’t return for it.

Morin was born in an apartment building one block behind Pine Tree Trading. As the son of French-Canadian millworkers, his first language is French, and he witnessed firsthand the impact of the mill and shop closures of the ’80s and ’90s. His customers were “the people who ran out of money, the people looking for jobs.” Other pawnbrokers, of varying degrees of repute, set up shop too. “I never felt — never, never — that someone coming through my doors should be seen as a victim,” Morin said. “These people were in a bad position, and they needed a few extra bucks. Suit coats or rags, once they got to my counter, they were all the same.”

The busiest time of every month was the beginning, when state-assistance checks were issued. The busiest time of year was late spring, when people spent their tax returns on what they’d given up over the previous 12 months. The most disheartening time was Christmas, when parents started pawning kids’ gifts within the week to afford to party on New Year’s Eve. A woman next door showed up the middle of every month, like clockwork, for the $15 she needed to buy a half gallon of vodka. Another woman once slipped him an envelope with an apology letter and five $100 bills inside, paying him back for a diamond pendant she stole years earlier. Morin refused the cash but kept the letter.

More than once, Morin alerted police to suspicious sales, one time helping break up a tool-burglary ring. His reputation as a fair, lawful businessman mostly kept the good customers in and the bad ones out, he says, and he’s transacted with everyone from millionaires to the penniless, city cops to prostitutes. His pawnshop — where he permitted neither drinking nor smoking — was often called “the only sober bar in town.”

As Morin talked, he breathed supplemental oxygen through a hose under his nose. Last spring, he tested positive for COVID-19. “I felt like I was going to die,” he said. He spent 30 days at Central Maine Medical Center, during which time he counted 300 get-well cards from customers. After discharge, his health continued to decline, and by midsummer, he’d lost 40 pounds. The business where he once spent 70 to 80 hours a week, Monday through Saturday, was shuttered for the first time in 33 years.

He was laid up at home as his four children sifted through stashes of gold coins and expensive watches, collector hunting knives and baseball cards, consulting him via Facetime. Selling off high-value items was always part of the plan — a pawnbroker’s version of a 401(k) — but not under such circumstances and with such haste. By then, Morin had decided it was time to close for good. Formerly empty storefronts in the neighborhood have, in recent years, been filled by a wood-fired bagel café, an underground cocktail bar, and a coworking space.

Sitting in the rocking chair, with his oxygen tank next to him, was a chance to say goodbye to the place. He’d listed the building, and several offers had already been made, with the most interest coming from upstart cannabis sellers. Before the pandemic, Morin had commissioned a new hand-painted sign for Pine Tree Trading — business had been good, even as many other Lewiston pawnshops sputtered out — but now he’d missed the opportunity to hang it. I picked up an old drill and examined a tag with an inscrutable string of letters. Pawnbrokers use secret indexing codes to record the terms, value, and date of a loan, and only three other people, Morin said, knew his. “See if you can figure it out,” he joked. Then, on a whim, he told me the ten-letter decoding sequence. His sons, standing nearby, couldn’t believe what they were hearing. Morin was ready to let it go.