By Philip Conkling

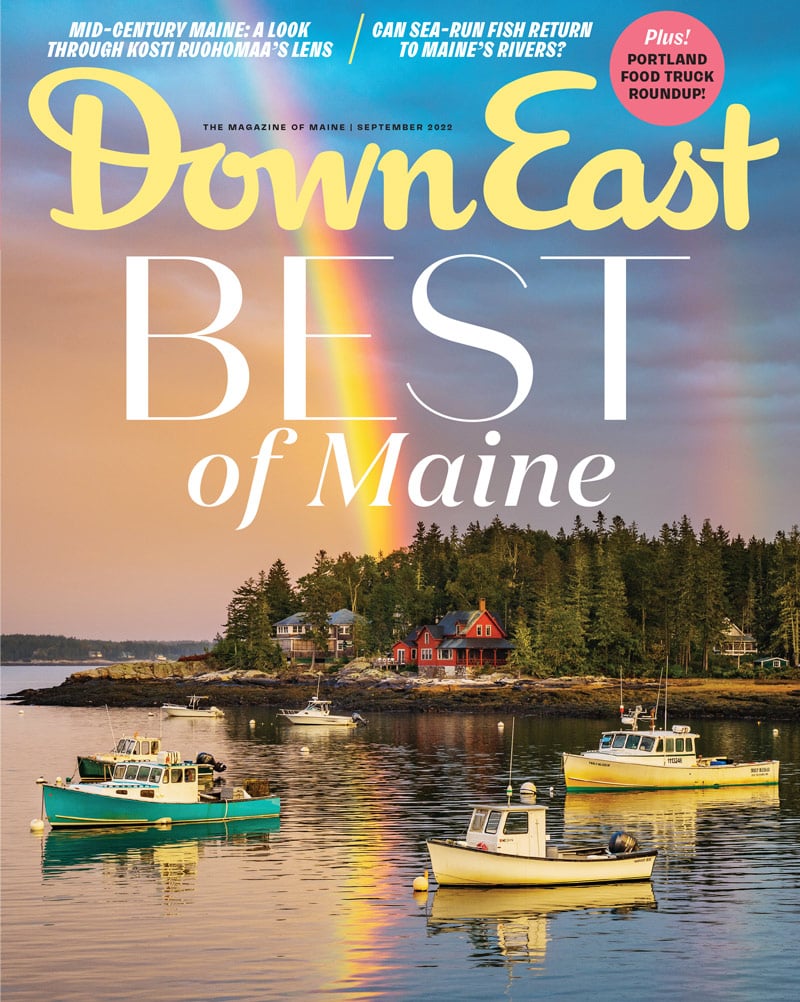

Photograph by Peter Ralston

From our September 2022 issue

For the past two and a half decades, I have lived alongside a shallow tidal cove, maybe a half mile wide and a half mile long, which empties out at low tide and refills when the sea surges back, lapping at the edges of the cove’s sandy, gravelly beaches and over its rockweed-covered ledges. Every 12 hours or so finds some new activity unfolding, an endlessly entertaining drama of fish and fowl, canoe and kayak, sail and skiff.

Last year, the abundance of pogies flipping at the surface drove the ospreys into a diving frenzy. In earlier years, silver-sided herring rippled through, particularly in the evenings, when the mercurial light of sunset backlit the cove’s dark edges, etching beauty and wonder into memory.

This has been the summer of the striper. At high tide, if you look carefully into the sun-flecked water along the shore, you can see them streaming by — and a lot of them are big. They are also hungry, voraciously so, which is why they are circling in the cove. Beyond the low-tide mark, where the cove begins sloping down, a large bed of eelgrass provides cover and nursery grounds for all kinds of recently spawned marine life, including juvenile lobsters, crabs, and fish.

This year, the cove’s stripers begin their daily rounds within these underwater feeding fields. They seem to swim counterclockwise, against the circulation of the incoming tide, in order to scare up the seemingly endless supply of green crabs and fish, scuttling from one hiding place to another. When they’re smaller, stripers are themselves quarry — for seals, sharks, the occasional raptor. Once they reach the age of three or four, when they weigh more than eight pounds, their only significant predator is a human with a rod and reel.

The commercial and recreational fishery for striped bass was nearly extinguished in the 1980s, a result of a vigorous, improvident commercial fishery, especially in Chesapeake Bay, one of the chief centers of striper abundance. One of the wonders of marine-vertebrate biology, which is hard for us land-dwelling species to appreciate, is that fecundity increases with age. Thus, a larger, older female striper may carry several million eggs, whereas smaller, younger females carry mere thousands. An effort to protect females from harvest until they can lay some untold number of eggs prompted rules limiting striper catches to fish over 28 inches — it’s now a hallmark of striper conservation from Maine to North Carolina.

Last week, I watched a neighbor and her Maine Sport fishing guide glide by in a small skiff at high water. She cast a fly with twin iridescent green lures that must look like a pair of floating green crabs to a striper. Bam! The tip of the rod suddenly bent as another catch-and-release drama unfolded, this one between a large, ravenous fighting fish and a novice saltwater angler.

The famous Maine seafood chef Barton Seaver, in his book American Seafood, urges us to try simmering the large head of a striper “in a broth rich with fresh herbs like parsley [and] to serve the head split down the middle, so that the rich marrow can be spooned out.” I have not followed Seaver’s advice, but I can recommend the thrill of intently watching the water in those myriad places along the coast where the beating heart of the ocean refreshes the infinite cycles of marine life.