By Will Grunewald

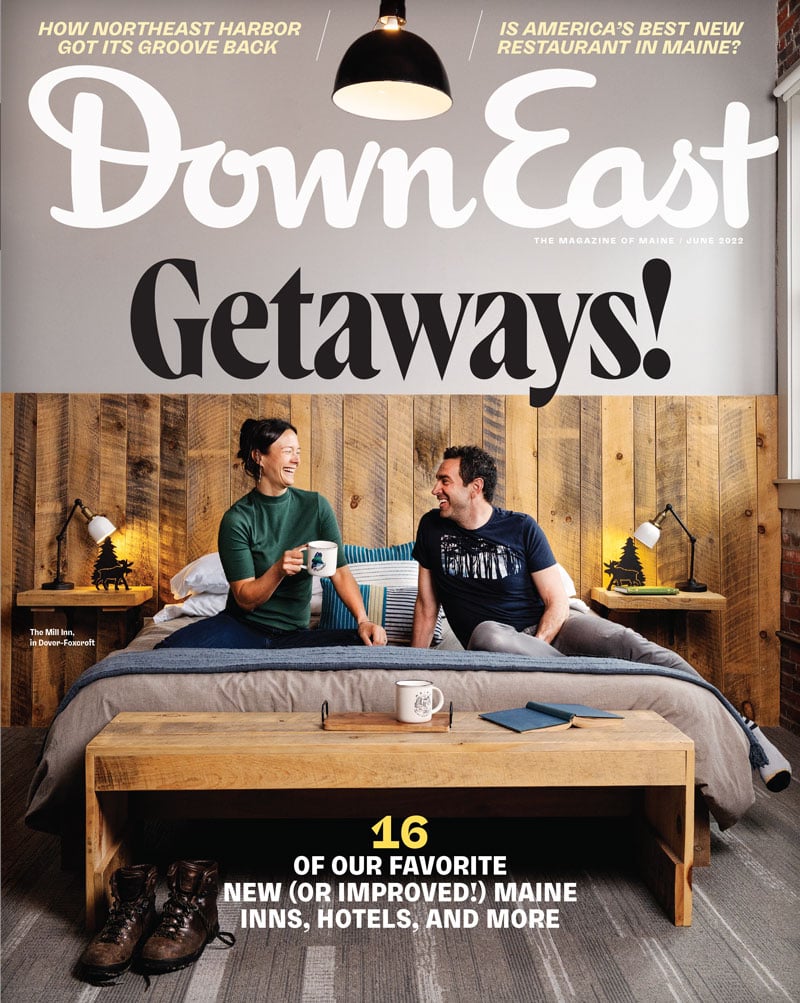

Photograph by Chris Evans

From our June 2022 issue

Last June, barefoot beachgoers in southern Maine found their soles disconcertingly stained black. Outlets from the New York Times to the BBC to Smithsonian Magazine covered the strange phenomenon, reporting on speculation that the carcasses of billions of tiny kelp flies were to blame. But the news cycle had moved on before the true culprit was quietly revealed, in a Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry newsletter that mostly circulates among a niche group of forest specialists.

The department had sent a sample to the U.S. Forest Service, which ran DNA tests conclusively identifying not the kelp fly but the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive species from east Asia. In their native range, the nearly microscopic insects suck sap from hemlock trees. At a later point in their life cycle, some sprout wings and move on in pursuit of certain spruce species that, in Maine, don’t exist. Consequently, winged adults die off here. This die-off was on a scale that researchers in the region had never seen, and it suggests a population explosion. Infested trees lose their deep-green luster, drop their needles, and stop putting out new branches. Many don’t survive.

Of course, insects haven’t been the only threat to hemlocks. Historically, the trees were not much prized for lumber, but they were targeted for the tannins in their bark. Those tannins came in handy for tanning leather — and even after being ingested by insects, it turns out, will stain feet too.