By Jesse Ellison

Photos by Michael D. Wilson

From our July 2025 issue

Has anyone described Maine’s most iconic mammal more memorably than Henry David Thoreau in The Maine Woods? “Singularly grotesque and awkward to look at,” he wrote. “They made me think of great frightened rabbits.” Thoreau seemed excited at first as he and his companions hunted, but it took just one success — a “murder,” in his words — for him to lose his appetite. “I already, and for weeks afterward, felt my nature the coarser for this part of my woodland experience, and was reminded that our life should be lived as tenderly and daintily as one would pluck a flower,” he added. “Every creature is better alive than dead, men and moose and pine trees.”

The Maine Woods was the culmination of expeditions Thoreau undertook in the 1840s and 1850s. By the 1930s, the state’s moose population had been so thoroughly decimated by hunting and habitat loss, as well as by a parasitic brainworm, that, after years of curtailed hunts, the legislature banned moose hunting altogether. At the time, estimates put the number of moose in Maine at a mere couple of thousand. But the hulking animals clambered back from the brink. Unthreatened by hunters, they started to thrive in the young forests left behind by intensive logging. The abundance of new, low growth was essentially an open buffet. Still, when a proposal to reintroduce moose hunting landed in the legislature, in 1979, it sparked controversy. Criticism came from both conservationists and hunters, but a bill passed nonetheless, introducing a lottery-based system of awarding licenses (hunters initially objected to the lottery entrance fee, which helps fund the Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife’s work). Opponents staged a sort of moose funeral in the State House, featuring a coffin, black arm bands, and a state representative playing taps on the trombone. A death certificate listed the cause of death as the “insensitivity of the State legislature.”

Nowadays, one thing about being responsible for the well-being of Maine’s moose population is that it involves a great deal of contact with dead moose. The hunting season runs from late summer through early fall, and one day last October, the atmosphere was decidedly celebratory at the check station in the parking lot of a convenience store in Jackman, the little town near the Quebec border that attracts both timber interests and sportsmen. A store employee used his phone to live-stream on Facebook as moose were weighed, a chain looped around the antlers and the entire animal hoisted into the air, hunters often posing for pictures alongside their quarry. Blood streamed onto the asphalt and ran in rivulets and eddies. An occasional splat sounded as innards and bags of ice packed inside the moose spilled from their torsos and hit the pavement.

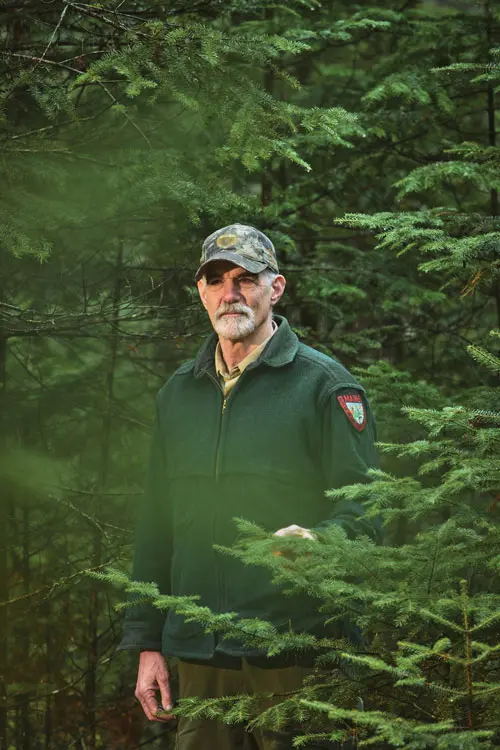

“Jackman: the Switzerland of Maine,” read a sign outside the store. The weather was the variety of cold and wet that cuts right to the bone. In the middle of the parade of dead moose stood Lee Kantar, the 58-year-old wildlife biologist whose job is to monitor the largest moose population in the Lower 48, with 60,000 to 70,000 of the animals living in Maine (Alaska, which is approximately 19 times larger, has about three times as many moose). Kantar is the first dedicated moose biologist employed by the state and the only dedicated moose biologist employed by any state. Tall and lean, with dark eyebrows and a trim white goatee, he has an eagle-like countenance. He wore a raincoat over his uniform with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife patch and, to help in the collection of data, he carried a buck knife and a wooden pencil.

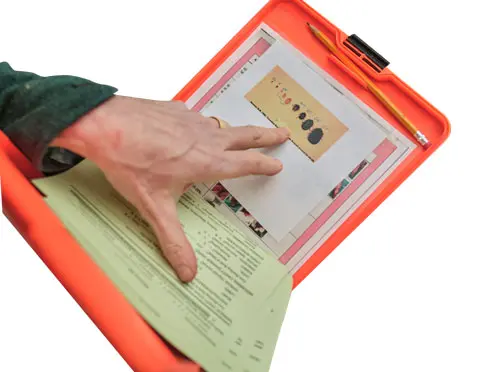

As each moose was weighed, he hoisted himself up onto truck beds and used the knife to pry teeth from giant jawbones — the growth layers of the teeth can be used to estimate a moose’s age, much like counting tree rings. With the pencil, he combed lines through the fur, looking for the biggest threat that Maine’s moose face today: the tiny white specks that are winter ticks. Maine’s moose population peaked around 100,000 a quarter century ago, and the subsequent decline is largely attributable to these little bloodsuckers.

Winter ticks don’t pose a direct threat to humans, since they rarely attach to people and don’t transmit any diseases to people, but they’re particularly dangerous to moose because they work in teams, interlocking their legs so that when one larval tick grabs onto a moose it brings hundreds of others along with it. Then, they feed off the same host through all three of their life stages — larva, nymph, adult. Their name owes to the fact that they hang on from fall through spring, straight through winter. One unfortunate moose can wind up playing host to tens of thousands of winter ticks. Some moose can live with ticks, but many, particularly those in their first year of life, when they’re growing, will succumb. It’s a miserable way to die, from anemia. Essentially, they very slowly bleed to death.

Moose severely infested with winter ticks are sometimes called “ghost moose” by scientists, because in rubbing against trees and rocks trying to get the parasites off, they scrape off all their fur. When Kantar and his team find dead calves in the woods, the bellies are more often than not full of food, but the internal organs are bloodless, colorless. Afflicted moose have been observed to simply tip over, seemingly out of nowhere, and never get back up.

The Challenges of Being the Country’s Only State-Appointed Biologist Dedicated to Moose

Moose biology is still a fledgling area of study. “In most jobs, you’re trained by a predecessor who’s trained by a predecessor, but in the field of moose biology, literally everybody is a pioneer,” says Pete Pekins, professor emeritus of natural resources and the environment at the University of New Hampshire. In 2019, Pekins nominated Kantar, who was a student of his as an undergraduate, for the Distinguished Moose Biologist Award, given annually by the North American Moose Conference and Workshop, a niche annual gathering for the moose researchers scattered across the United States and Canada. Kantar won the award handily, thanks to his efforts to merge the latest research with management tactics. “He had no tradition to fall back on, and he has created the most progressive program that there is in the country,” Pekins says. “Maine is incredibly lucky to have him.”

He attended Brandeis University, graduating in 1988, then promptly through-hiked the Appalachian Trail. Five years later, he went to the University of New Hampshire to study wildlife management, before heading to New Mexico State University, where he got his master’s degree and met his wife, Danielle D’Auria, a bird biologist. They both worked out west for a bit, then, thinking about children, decided to try to move back east, closer to their families. In 2005, the position as deer biologist for Maine’s Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife opened up. Kantar got the job and, six months later, D’Auria was hired for the department’s habitat group. Eventually, she moved over to the bird group. They live in Bangor and have two teenage daughters.

When Kantar joined the department, Karen Morris was in charge of moose management, and she was something of a legend. She was the first female biologist the department ever hired, and she studied bears before being tapped to take on moose as well, in 1980, the year moose hunting became legal again. Morris retired in 2008, and Kantar stepped in to take over moose. It made sense for the state’s deer biologist to also handle moose, since both species are in the same taxonomic family (which also includes caribou and elk, although the former has been gone from Maine for more than a century and the latter for longer). For five years, Kantar split his focus, until the commissioner of the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife proposed that both species were so critically important to the state’s culture and identity that they each warranted a dedicated biologist. Given the choice, Kantar picked moose. Deer are ubiquitous, found across all 50 states. Moose, he says, are something else: “They’re iconic. The creature of the north woods. They’re really, really unique. Who wouldn’t want to be able to study something like that?”

Kantar set out to make moose management as scientific a practice as possible, so he leaned in to data collection. A decade ago, he started spending a week every January flying over moose country in a helicopter with aerial-tracking specialists from New Zealand. The first year, the team used nets to capture a total of 60 moose (30 calves and 30 adults), looping slings around them so they could be lifted and weighed, then attaching leather collars with embedded radio transmitters. Kantar modified the collars himself, adding plastic tubing that allows them to expand as the moose grows and eventually fall off. Now, every winter, he and his crew go back out and put dropped collars on new moose — there are always about 70 collared moose roaming the Maine woods.

The data from the new tracking program was central to a 2018 paper, in the Canadian Journal of Zoology, showing that 70 percent of moose calves in Maine and New Hampshire were dying from severe emaciation due to winter ticks, and that on average, each animal hosted 47,371 ticks. The paper also explained that moose that survive a hoard of winter ticks are still impacted, particularly when it comes to reproductive health. If female cows weigh too little, they stop ovulating. In healthy moose populations, about a quarter of births result in twins, but in Maine, virtually none do.

In late spring and early summer, a female winter tick lays as many as 4,000 eggs. A few months later, the new ticks climb nearby vegetation and wait to encounter a host. They can sense the vibrations and carbon-dioxide emissions of large mammals from 20 yards away. They hitch themselves to each other with their interlocking legs and grab on. This interaction is age-old. The difference now is that winters are getting shorter. Young ticks can’t survive winter temperatures without a host, and climate change has extended their window of opportunity for finding a host. “With these ticks,” Pekins told me, “moose should be the iconic symbol of climate change.”

When the moose population faces stressors, so does Kantar. “I take a lot of flak,” he says. “I’m used to it. I’ve got broad shoulders.”

Ben Simpson, a fellow wildlife biologist, works for the Penobscot Nation, which manages its own lands and whose members can hunt moose without participating in the state’s lottery system. He’s often in touch with Kantar, who he says is “probably one of the most passionate biologists that I’ve ever worked with — his love and appreciation for moose in Maine is really obvious.” At one point, while I was with Kantar, Simpson called to ask whether a moose that had been acting strangely and then drowned could have been afflicted by brainworms and whether its meat might be tainted.

“His job is a million times more difficult than mine,” Simpson says. “He has to deal with the general public and I do not. People think they know more than the experts. If they’re not happy with what’s happening, the bad guy is the one who’s making the decisions.”

The Rationale for Hunting Moose in Maine

Maine is divided into 29 wildlife-management districts, based on shared environmental characteristics, and every year, Kantar and his colleagues at the Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife have to use data they’ve collected to determine how many moose-hunting permits to issue for each district. In total, they issue about 4,000 permits per year, but that number could go up or down according to how the moose population seems to be doing. Most years, at least 70,000 hunters apply for those permits, so the odds are already against them. Decisions to decrease the number of permits can be unpopular.

So too can decisions to intensify the hunt, even selectively. A couple of weeks after visiting Kantar at the checkpoint in Jackman, I drove north again, to meet him at a hunting lodge up past Moosehead Lake. He was keeping tabs on an adaptive hunt, outside of the normal lottery system. This one, set to run for five years in a subsection of one management district, provided additional permits for antlerless moose, with the idea being to target females. But convincing people that killing cows, possibly in the presence of their calves, might be in the best interest of the species is its own challenge. “It is so counterintuitive to the public, that experimental hunt,” Pekins told me. For generations of deer hunters, the notion of shooting a female deer was absolutely anathema. “Where I grew up, it’d be more acceptable to beat your kid than to shoot a doe.”

Kantar’s idea, born of years of study and experience, is that part of the problem with winter ticks, in addition to climate change, is that the population density of Maine moose has grown too high in certain areas. In more natural environments — ones not crisscrossed with logging roads, interspersed with recently cut woods, or abutting farmland or new development — moose live at much lower densities. “They require so much feed to support these massive bodies,” Kantar says. “They can’t be like deer. They have to spread themselves out. And we have inflated populations also because there’s no predation.” Wolves were extirpated from Maine by the end of the 1800s. Coyotes only rarely hunt moose, preferring smaller prey. He estimates that, in some parts of the state, the population is as much as six times its natural size.

If moose are overabundant, the theory goes, winter ticks become overabundant too, thanks to having a ready supply of hosts. Fewer moose, then, could mean fewer ticks, which could mean healthier moose — and hunting females better suppresses the population than hunting males. Essentially, the adaptive hunt posed an experiment to see if killing moose would be good for moose. The problem, Kantar was finding last fall, was that hunters weren’t killing enough of them, averaging only about a 30 percent success rate per permit, compared to 60 to 80 percent in the statewide bull hunt.

Kantar is a hunter too — “a late onset” one, he told me, since he didn’t get into it until he was in his 30s. “I’m completely obsessed with deer hunting,” he said. “I grew up outside. I’m a child of the ’70s. I love animals and all that kind of shit. I love moose. But hunting, there’s so much philosophy. There’s all these layers to it.”

He has done the moose hunt just once, in 2014. His number was drawn in the lottery. After killing a bull, he opted for the method he uses with deer: quartering, which essentially means doing a rough butchering of the animal in the wild, leaving the hide, guts, rib cage, and most of the head in the woods for other animals to feast on. It’s the way moose are handled in Alaska, for instance, where there isn’t any other option. There, hunters fly in and out on small planes, spending extended time in the bush, staying alert for grizzly bears. Hauling out the entire animal simply isn’t realistic.

Kantar was about a mile from the road when he got his moose. He and a friend quartered it and hauled it to his Toyota Tacoma — a “little truck” he says — in one and a half carry trips. A photo of the truck bed loaded with all the gear and the meat later ran in a brochure underneath the rubric of what people “don’t need” when they head out on a hunt. But hunting is a cultural thing, Kantar reminds himself. Of all the hunters who came through in the days I spent with him, only one had quartered his moose in the woods. What’s far more common is traveling with loads of gear, on clanging trailers, including heavy chains to haul moose carcasses out of the woods. Often, a hunting party arrives with more than one such get-up.

Extra gear and vehicles can pose a problem, especially for this adaptive hunt. Cows are shier and more reclusive than bulls. They can’t be called in closely by imitating the sound of a mate the way a bull can. So when trucks are bunched together on logging roads, which Kantar accepts is just human nature, the odds of a successful hunt diminish. “The difficulty of managing wildlife is humans,” his former teacher, Pekins, told me. “We’re the hardest things to manage. It’s a great lesson in science. You can set up the greatest experimental protocol ever, but if humans are a part of the equation, you just can’t control their behavior.”

This wasn’t the first adaptive hunt Kantar had instituted, and the previous one had taken some fine-tuning. It was put in place around a broccoli farm in Aroostook County. Moose love broccoli, and Kantar learned that the farmers were struggling to keep the moose out of their crop. So he worked with them to bring in a small number of hunters. Initially, it was problematic — some hunters were hunting while the farmers were working in the fields, and the farmers felt they weren’t sufficiently respecting the land. Then, Kantar changed things up, partnering with a friend who runs a program for disabled veterans. Now, the Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife issues 25 permits for the adaptive hunt every August. Veterans, some of them in wheelchairs, manage to shoot enough moose to protect the broccoli. Kantar realized he might have to rethink aspects of the hunt up near Moosehead too, or possibly scrap the idea altogether.

The Sound of Death: The Emotional Toll of Monitoring Maine’s Moose

When I called him this spring, he answered with a heavy sigh. April is a month of death, he told me, and he’d been woken up at 3 that morning by the sound of the grim reaper — the notification tone he has set for the app that tells him that a collar hasn’t moved for six hours. Either the collar fell off or the moose is dead. It’s almost always the latter.

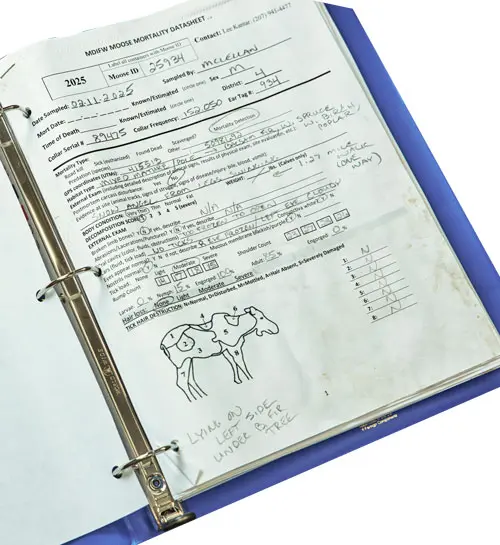

Kantar would have to find the body and perform a necropsy, assessing a cause of death. Winter ticks were almost certainly the culprit. Had the moose curled up and fallen asleep under a tree and never awoken? Or had it just tipped over dead? He’d get some idea of the circumstances once he got out there.

He told me that he’d recently been shown a video that was even more disturbing than what he sees out in the field when he conducts a moose necropsy. Someone’s doorbell camera had captured the moment a moose walked onto the front lawn, laid down, and died. “It’s so upsetting,” Kantar told me. “It’s awful to see that.” He said that one of his younger staffers, on a long drive up to a necropsy, had recently pointed out to him that he deals with dead moose in the fall and dead moose in the spring. Hunting season followed by tick season. The staffer asked him if he was all right.

“Nobody had really asked me that,” Kantar says. “No, I’m not okay. It sucks. We live in a human-impacted system. We don’t live in a natural state. We have a warming climate and a lot of ticks. They’re going to kill the calves. While science has an answer, it doesn’t mean it has a fix.”