As told to Ron Joseph

From our April 2023 Animals issue

Mainers have twice attempted, unsuccessfully, to re-establish herds of woodland caribou that roamed the north woods before market hunters slaughtered them in the 19th century. Twenty-three Newfoundland caribou released in Baxter State Park in 1963 dispersed and gradually died off. Then, in the late 1980s, a privately funded group called the Maine Caribou Project tried again, but disease, bears, and coyotes wiped out the radio-collared herd within a few years. Dr. Mark McCollough led that second attempt, a precursor to a career as a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service biologist and an accomplished wildlife artist (you’ve seen his work: the chickadee and loon on Maine license plates). We asked the since-retired McCollough to reflect on the endeavor.

“IN OCTOBER 1986, an ad hoc group invited me to the Augusta office of Glen Manuel, commissioner of the Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife. Newfoundland biologists had agreed to help Maine reintroduce caribou by providing animals in December. I wasn’t in Commissioner Manuel’s office more than five minutes when he asked, ‘Would you be interested in leading the caribou project?’ I accepted my first job out of the University of Maine with reservations, because little planning had been done, money hadn’t yet been raised, the logistics for transporting caribou were lacking, and it wasn’t decided where in Maine the nursery herd would be held. I had just six weeks to implement a high-profile, complex wildlife project involving two countries.

Newfoundland biologists in helicopters captured 35 caribou with tranquilizer darts. Unfortunately, 13 died during capture and transport. The surviving caribou — two males and 20 pregnant females — were trucked across Newfoundland in a blizzard. At Port-aux-Basques, in 80-mile-per-hour winds, the truck with the sedated caribou rolled onto the 567-foot ferry and was fastened with heavy chains. The terrifying 125-mile crossing to Sydney, Nova Scotia, was like scenes from The Perfect Storm. Halfway across, amid 60-foot waves, the bow buckled, bending steel I-beams. Emergency pumps kept the ferry afloat. As it became top-heavy with sea ice, the alarmed captain said, ‘We may have to ditch the ship.’

After landing in Sydney, the caribou truck traveled through blinding snows to New Brunswick and Maine. The MV Caribou went to dry dock for repairs for the next six months.

It was decided to house the caribou at the aging deer-research facility at UMaine, in Orono. The university’s veterinarians could quickly administer care to an injured or sick caribou, top-notch wildlife professors were eager to assist, students could help feed and care for the caribou, and the public and media had easy access for viewing the herd. High deer density in the forests surrounding the pens was a disadvantage, though, because deer carry a brain-worm parasite that’s lethal to caribou. Knowing that, veterinarians treated them with ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug.

Caribou exiting the truck into the enclosure at Orono was an emotional high and a relief. There were dozens of media organizations in Newfoundland for the capture, including the CBS Evening News and the Canadian Broadcasting Company. So in Orono, hundreds who’d been glued to news reports greeted us at the pens.

Another high was the birth of 50 calves from 1987 through 1989. Unfortunately, we lost some to bacterial infections. It was also gratifying to observe the joy of 86,000 Mainers visiting the pens to see a once-native species. Many believed it was our moral duty to right a wrong.

The lows, of course, were the caribou deaths, including of the ones released in and near Baxter State Park. The first release, in April 1989, included 14 young caribou raised in Orono. Approximately half were killed by bears, and the others died of the brain worm acquired in the pens. January 1990 delivered an unexpected blow when the Baxter State Park Authority denied our request to release caribou. Great Northern Paper kindly offered a release site for the remaining 20 radio-collared caribou. But most of these were dead by October 1990.

It was devastating and emotionally draining to face the media when the animals kept dying. Jane Goodall, the global wildlife-conservation icon, spent an afternoon with me at the caribou pens. She was very sympathetic, as were many Mainers who appreciated what we were attempting to accomplish.

A Maine caribou herd today would have generated pride that we’d restored a species previous generations destroyed. On the other hand, it would have been increasingly difficult for woodland caribou to survive. Climate change is affecting Maine’s snow regime, and caribou require deep, fluffy snow. Their large hooves are adapted to pawing through it, to expose nutritious ground lichens. In recent years, we are getting more rain events in winter, and layers of ice on top of snow make feeding nearly impossible — the food is there, but they can’t get to it. I’m still asked if Maine should attempt another caribou-reintroduction project, but I don’t think it’s possible now.

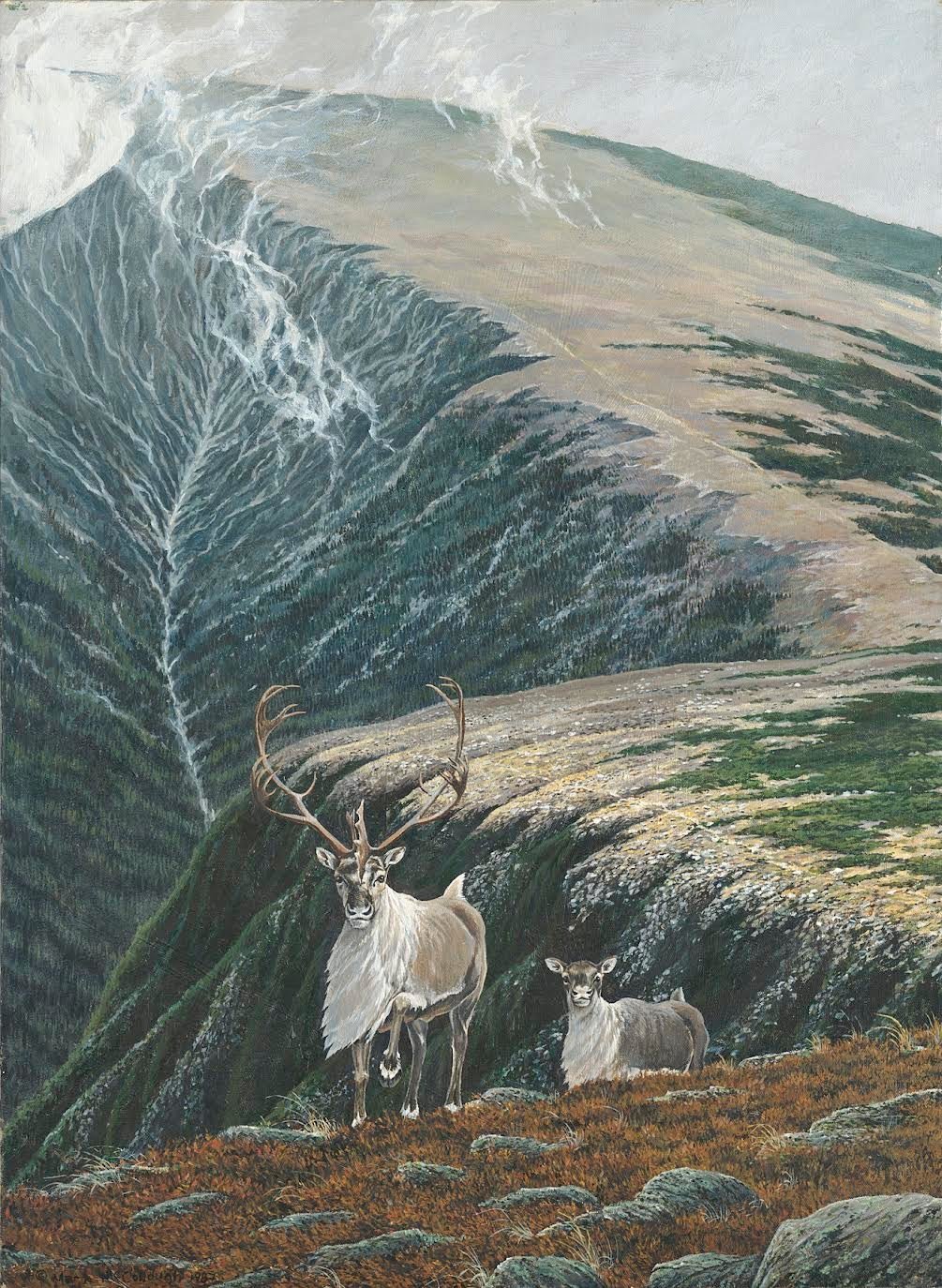

We made hundreds of prints of my caribou art to help raise funds for the project. My mother said my first word was ‘bou,’ after seeing an illustration of a caribou, and caribou remain a favorite topic for my art. They’re emblematic of the barren landscapes of the north. My wife and I have often visited northern Canada and Alaska just to be among the herds. They’re extraordinary animals that I wish were still in Maine.”