Muskie’s opponents, one New York Times writer proclaimed in 1970, “think of Maine as a hick state that is justly celebrated for lobsters, potatoes, and summer holidays, but not for producing presidential candidates.”

By David Shribman

From our April 2022 issue

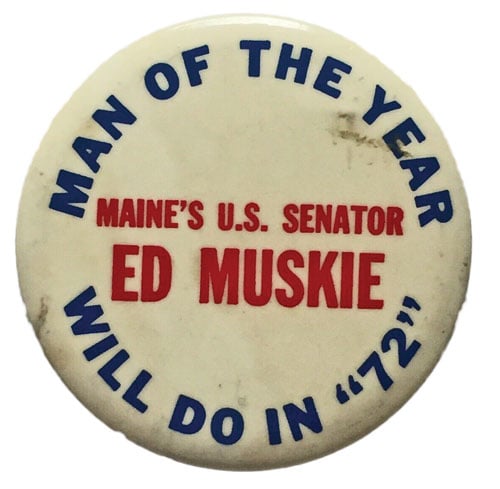

To many, his name evokes little more than one of the great also-ran stories in contemporary American politics, a brief comet that lit up the electoral heavens and then flamed out. But in Maine — in modest Democratic Party town offices, in the power corridors of Augusta, and in the wide sweep of the state’s civic life — Edmund Sixtus Muskie is a celestial giant, a star distant enough that its light still reaches us long after its death. The arc of his political career, from his beginnings as a state rep in Augusta to his tenure as U.S. secretary of state, is arguably the Big Bang of Maine’s modern political universe — in particular, his 1972 presidential-primary campaign, which saw “the Man from Maine” go from front-runner to lost cause in a matter of weeks.

The son of an immigrant tailor, Muskie was born on the eve of World War I, in Rumford, where he grew up speaking Polish at home. He was valedictorian of both his high-school and his graduating class at Bates College, a debate champ, and an outspoken admirer of then-president Franklin Roosevelt. His high regard for FDR made him something of an outlier in Maine, where political luminaries — from Joshua Chamberlain to Percival Baxter, Hannibal Hamlin to Margaret Chase Smith — were all but uniformly Republican.

When Muskie was elected as a Democrat to the state legislature in 1946, following nearly four years in the Navy during World War II, Maine was among the nation’s most devout GOP strongholds. The last 90 years had seen just three Democratic governors (and 29 Republicans). A Democrat hadn’t represented Maine in the U.S. Senate since Muskie was a toddler, and he had never seen the state deliver its electoral votes to a presidential candidate from his party. In 1936, when FDR won a landslide reelection, only Vermont joined Maine in voting against him.

So it was an upset when Muskie was elected governor in 1954. He served two two-year terms before being elected to the U.S. Senate. Then, in 1968, vice president Hubert Humphrey plucked Muskie for his running mate, and although Humphrey lost to Richard Nixon, Muskie’s polish and candor impressed both the party brass and the press. By the spring of 1970, both were anointing him the front-runner against Nixon in 1972.

But Muskie was an imperfect candidate. Though he was a mighty debater and legislator, he often fell flat connecting with voters. Pundits took him to task for lacking “pizzazz, savvy, and chutzpa,” as one New York Times reporter put it. “He could absorb details of arms-control negotiations, and he knew the fine print of environmental legislation,” campaign chronicler Theodore H. White wrote, “but he simply could not speak simply.”

On the flip side, beneath his wonkish public persona was a temper that staffers and colleagues regularly described as “volcanic.” Stories of Muskie lashing out at the press corps and other inquisitors were legendary, and the press didn’t shy from acknowledging the candidate’s irascibility — even in backhanded compliments, as when a New York Times editorial praising Muskie’s uncharacteristically expressive response to 1971’s Attica Prison riot declared, “If the ability to feel something passionately is the opposite coin of the fabled Muskie temper, hurrah for that.”

Ironically, it was feeling something passionately that sunk Muskie’s campaign. On February 24, 1972, in New Hampshire, the site of the first presidential primary, the conservative and influential Manchester Union Leader printed a letter to the editor claiming Muskie had recently laughed at and condoned the derogatory term “Canucks,” referring to French-Canadians, an important New England voting bloc. Whether the paper’s firebrand publisher, William Loeb, knew it or not, the letter was a phony, planted by operatives supporting Nixon. Loeb lambasted Muskie in an accompanying editorial, and the paper repeated some previously published gossip about Muskie’s wife telling dirty jokes.

Two days later, Muskie stood on a flatbed truck in front of the paper’s headquarters, before a crowd of reporters and others, furiously denying the letter’s accusations and denouncing Loeb for attacking his wife. The publisher was a “gutless coward,” Muskie fumed, declaring, “It’s fortunate for him that he’s not on this platform beside me.” At one point, the senator grew so seemingly agitated, he fell silent, and his cheeks were visibly wet. For five decades, observers, colleagues, and commentators have debated whether Muskie wept that day or the droplets on his face came from falling snow. The major papers reported tears.

Initially, Muskie’s team didn’t realize the impact of those ostensible tears. In fact, most thought the candidate’s performance demonstrated his compassion, that “he’s got an emotion that connects with people on an individual basis,” as campaign manager and longtime adviser Berl Bernhard later put it. But on March 7, Muskie’s showing in the primary fell far short of expectations. He won, as a candidate from a neighboring state was expected to, but with less than 50 percent of the vote, and a narrative of weakness dogged him in the weeks that followed. His poll numbers sank, and he won just one more primary before withdrawing in late April.

“He was punished for being a strong candidate and punished for not winning big enough,” former aide and Portland lawyer Charles Micoleau told Bates’s Muskie Archives oral-history project, years later.

But seldom has failure produced such success. “One of the unintended consequences of the ’72 campaign,” explains Colby College political-science professor L. Sandy Maisel, “was bringing a whole group of young Democratic politicians to the fore who would dominate Democratic politics for decades to follow.” For many of the men and women who ran it, Muskie’s flawed presidential campaign was transformational, turning young staffers into the core of a new crop of Democratic power players.

“That campaign gave all these Maine figures enormous exposure and experience,” says Harold Pachios, another Portland lawyer, who joined Muskie as a staffer for his vice-presidential campaign in 1968 and became chairman of Maine’s Democratic Party in 1976. “We traveled around the country, met all the important people in politics. I knew every single leading Democrat in California, and others had the same experience I did.”

“The people he brought into politics, and later, those he inspired, created a huge cultural change for Maine,” says Saint Louis University School of Law professor Joel Goldstein, who is writing a biography of Muskie. Among that group were Shepard Lee, the late auto mogul and Democratic fundraiser; Nancy and the late Bruce Chandler, who became a Democratic National Committee member and a Maine Superior Court justice, respectively; Don Nicoll, a policy planner and veteran of many state boards and commissions; Jane Fenderson Cabot, who joined Rosalynn Carter’s White House staff; the late Peter Kyros, who represented Maine in the U.S. House, and Eliot Cutler, who ran for governor twice.

Perhaps most notably, the group includes George Mitchell, who after serving as Muskie’s campaign manager in 1972 became a federal judge, then the U.S. Senate majority leader, occupying Muskie’s former seat, then a renowned diplomat in Northern Ireland and the Middle East. Mitchell joined Muskie’s staff in 1962, often driving the senator around Maine, staying with him in private homes or tiny, rural motels. “And he talked a lot to me, and I listened, and I observed him going about the task of being a senator,” Mitchell told a Bates oral historian. “Just about everything I’ve learned about public service, I learned from him.”

By the time President Jimmy Carter appointed Muskie secretary of state, in 1980, those shaped by him and his campaigns were known simply as “Muskie people,” in the same way those in John F. Kennedy’s orbit remained “Kennedy people” long after they’d become senators or ambassadors or commissioners of the NBA. “Muskie people” came to include those who’d never worked for the senator but who turned to him for counsel, including Maine governors Kenneth M. Curtis and John Baldacci. By the time Muskie died in 1996, just months before Bill Clinton swept the state in his re-election campaign, Maine was in the midst of a political transformation that has seen it deliver all or most of its electoral votes to Democrats in eight straight presidential elections. In a state where Muskie’s success was once considered a fluke, his party occupies the governor’s office, both seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, and both chambers of the State House. “None of that might have happened,” Pachios reflects, “if the failure of 1972 hadn’t happened.”