Illustrated by Erwin Sherman

FIRST FRUITS

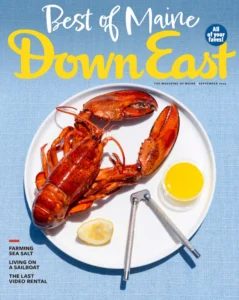

Wild blueberries took root in Maine 10,000 years ago, after the glaciers receded, and began growing in the acidic, sandy soils of what are now Washington and Hancock counties and the mountaintops of the midcoast. The plant flourished as forests were cleared for timber. Indigenous peoples, who called the plant “star fruit” for its five-pointed calyx leaf, which produces the blossom, dried the berries on birch bark for food in winter and boiled them for teas, dyes, and medicines.

In the United States, Maine is the center of commercial wild blueberry harvesting.

GROWTH SPURT

These berries are “wild” because they grow in their natural ecosystem — there‘s no artificial breeding or genetic modification for traits like long shelf life. The soil is never tilled. Growers nurture the plants by managing pests and removing obstacles to growth, like weeds and rocks. “What we’re doing is much less like farming and much more like helping Mother Nature along,” says Bruce Hall, an agronomist with Wyman’s. Two-thirds of each plant grows underground, spreading via a horizontal shoot system. Any field has thousands of genetically distinct plants. That diversity makes the berries more resilient to disease and lends to their unique flavor: tangy, sweet, and tart.

Wild blueberry plants grow about 12 inches high. They are referred to as lowbush to distinguish them from ordinary highbush berry plants, which can grow up to 6 feet tall.

WILD KINGDOM

The barrens create an ecosystem where bears, upland sandpipers, and more than 160 species of native bees feed and raise their young. The barrens also host insect predators like crickets and beetles, which feed on pests that threaten the berries. “It’s a naturally occurring ecosystem,” Hall says. “It’s not just about the plant but about keeping natural checks and balances in play.”

Bees play a starring role in the wild blueberry harvest. Wyman’s brings in hundreds of bee colonies in late spring to help pollinate the plants.

HARVEST TIME

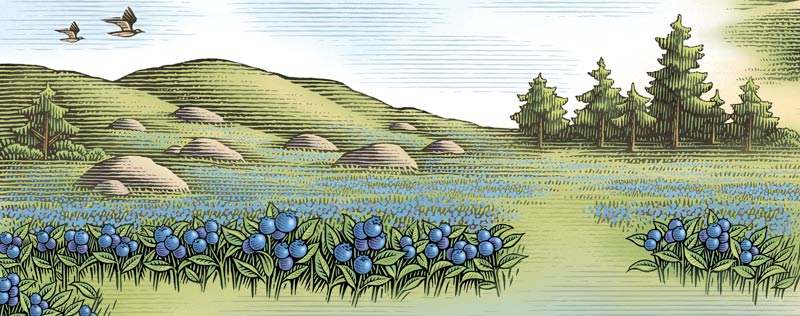

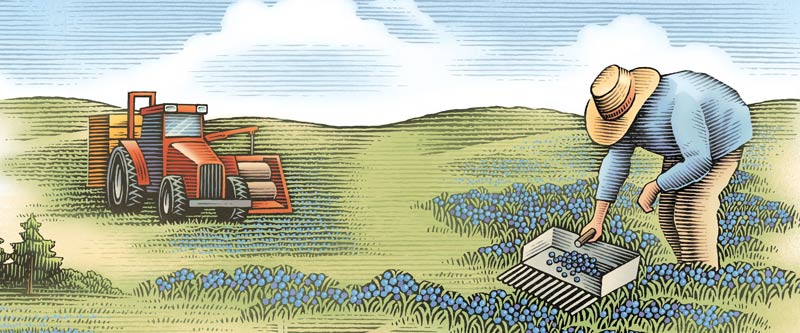

Once the barrens turn indigo in late July, growers reap the berries using mechanized harvesters or long-tined hand rakes. Most fields are mechanically harvested, but hand-raking is still used for rocky, hilly fields that tractors can’t reach. The raking season normally lasts until Labor Day.

The tiny berries are about a quarter the size of marble-size berries and grow on a two-year cycle. Each season, half the berries are harvested, the others are pruned.

OUT OF THE BARRENS

After the harvest, the berries are taken to processing plants, where they are cleaned and sorted. Within 24 hours of being picked, most berries are individually quick-frozen, which seals in the color, flavor, and nutritional benefits.

In September, after the harvest, the leaves turn a deep shade of crimson.

INTO THE WORLD

About 1 percent of the berries are sold fresh, found in farmers’ markets and grocery stores throughout Maine in August. Most berries are frozen and shipped all over the world to be used all year long in wild blueberry pies, smoothies, muffin mixes, savory sauces, and a lot more.

Blossoming into an Industry

In the 1860s, the Civil War helped transform Vaccinuim angustifolium from a foraged fruit to commercial crop, when seafood canneries along Maine’s coast began shipping wild blueberries to Union troops to fend off scurvy. In the 1880s, cannery owners started incorporating wild blueberries into their offerings. By 1900, that included Jasper Wyman — who’d operated a seafood cannery in Milbridge since 1874 and stewarded barrens of his own. Clarence Birdseye pioneered food freezing in 1925, and by the 1940s, most wild blueberries were being frozen to preserve flavor, color, and nutrients.

Along the way, collaborative efforts have helped foster the crop‘s sustainability, and its success. Industry representatives petitioned the state to levy a tax on the industry to fund research and outreach and formed an advisory committee to oversee it. In 1945, the Maine Wild Blueberry Commission was established to promote the industry. University of Maine research into best practices in cultivation, pest management, and other issues, as well as outreach from the university‘s Cooperative Extension specialists, has helped the industry thrive.

Now in its 147th year, the company Jasper Wyman founded is the oldest of Maine’s major wild blueberry processors and one of the largest, and it‘s the nation’s top-selling retail brand of frozen fruit. Still based in Milbridge, it also has operations in eastern Canada. In Cherryfield and Deblois, Wyman‘s processes, freezes, and cans wild blueberries from local growers, as well as 12,000 acres of wild blues it farms. They go into an array of products, from scones to jams, and Wyman‘s own line of products, including powder, juice, and bags of frozen fruit.