By Brian Kevin

From our January 2015 issue

Stream or download an audio version of this story, read by the author.

Susan Pierce couldn’t pinpoint the moment she fell in love with Norman Grenier — poor Norman, serious and sensitive Norman — but it was the night she overdosed at her boyfriend Dickie’s place in 1982 that something inside of her first stirred. Norman had found her convulsing on the bathroom floor after shooting up cocaine. He had put a toothbrush in her mouth to keep her from biting off her tongue, then stayed with her on the floor until she came to. When she got herself right, the first thing she saw was his pale face and reddish hair and those somber dark eyes looking down at her.

Susan was into bad boys then. At 23, she’d been into them at least since she dropped out of high school in Clinton — Maine’s dairy capital, population 2,500ish — and set out for New York. She met her fair share of them while dealing cards in a private Manhattan gambling club, and as a sometimes-paramour to the club’s hedonistic patrons, she was introduced to champagne, caviar, and cocaine. She’d stumbled at dawn out of Studio 54 more times than she could remember. For a few years there, all Susan Pierce wanted from life were nice clothes, jewelry, and limousines, and she’d learned long ago how to use her looks to get what she wanted. She was blonde and shapely, with come-hither eyes she could turn on and off. Years later, when everything fell apart, the newspapers would describe her even in the throes of addiction as “an attractive, fashionable blonde.” Poor Norman, meanwhile, they called “shabby looking and overweight.”

But Susan’s attraction to Norman never had to do with looks. At first, before the night of the overdose, it mostly had to do with his cocaine. Burned out on a life of big-city excess, Susan had come back to Maine intent on law school — she’d once been a straight-A student — but it turned out she was still into bad boys, and she should have known she’d end up on multi-day coke binges with a stupid thug like Dickie. The first time Norman had walked into Dickie’s place, Susan had thought that he radiated — what, exactly? Confidence, intelligence, subtlety. He wasn’t a roughneck lout like Dickie or a swaggering fink like the high rollers in Manhattan. Here, Susan thought, was a businessman, a quiet pro who’d moved up to Maine from Rhode Island and was giving away coke to guys like Dickie, recruiting them as his street-level dealers.

After the overdose, Norman stopped coming around for a while. He called Susan weeks later to apologize for his absence — he’d been banged up in a car accident, he said. Only then did she realize that Norman had been hanging around Dickie’s mostly to see her. She left Dickie for Norman and didn’t look back.

The two of them got a place together in Swanville, just north of Belfast, at the end of a forested cul-de-sac atop a small hill. Susan had a driver’s license, which Norman, after his accident, did not. So together they made periodic rounds to visit the network of coke dealers that Norman had assembled. They rented a car and put a cooler of Budweisers in the back. With the windows down and the radio up, they drank the Buds and held hands and drove the back roads of coastal Maine, carefree as any hell-raising pair of rural twenty-somethings. It was an all-American scene right out of a John Cougar Mellencamp anthem — all except for the drugs.

Here and there, they stopped to trade coke for cash and maybe get high with Norman’s associates. There was Linwood Jackson, who sold in large volume to coworkers at the Champion paper mill in Bucksport. There was Mike Massey, whose kids loved to play on the floor with Norman while their parents got high in the bedroom of their trailer. And there was Billy Christensen, an on-again, off-again woodcutter, kind of a wispy guy whose speech impediment sometimes made his Ls sound like Ws. Susan thought of Billy as a more or less likeable loser, but Norman considered him a friend.

Occasionally, Susan and Norman drove to Boston, then hopped a commercial flight to Miami, where Norman met his supplier. Jay Hart was a flashy loudmouth like the big shots back in Manhattan. He drove a Ferrari, wore his hair slicked back, and swaggered into the room when Susan and Norman met him at his home. Susan was never involved in the deals — Jay and Norman did business in another room while she and Jay’s pretty girlfriend chatted in front of a big-screen TV. Sometimes she stayed at the hotel. Norman never talked shop, and Susan never handled — never even saw — the money or drugs. Whatever changed hands at Jay’s went into a suitcase, and that was that.

Still, the visits entailed a slight rush of danger that turned Susan on. She signed all the hotel registers and flirted with the rental car clerks, deflecting any suspicion with the charm that had never failed her. Sometimes Jay said ominous things. Once she heard him remind Norman never to snort his own product. “That’s what gets dealers into trouble,” Jay said, “and you do not want to be in trouble with me.”

But once the deals were made, she and Norman just lounged by the hotel pool, had dinner brought down, maybe did a few lines, and enjoyed some sunshine before heading home. Once a stewardess mistook them for honeymooners. On the whole, the Miami trips felt to Susan like little vacations, pleasantly pedestrian.

With the windows down and the radio up, they drank the Buds and held hands and drove the back roads of coastal Maine, carefree as any hell-raising pair of rural twenty-somethings.

When they weren’t doing or distributing drugs, life in Swanville felt that way too. They got a dog, a yellow Lab they called Yeller, and Norman doted on him. Susan cut Norman’s hair on the porch and bought him clothes, sprucing him up the way that girlfriends do, which suited Norman just fine. She loved to cook, and Norman loved to eat the roast chickens that she basted in the way her French-Canadian mom had taught her. They had money, but they lived discreetly, splurging only on hotels in Miami, Susan’s wardrobe, and some nice furniture for the house. Leaving money or drugs sitting around was out of the question — even Susan didn’t know where Norman stashed coke or cash. For a few weeks one spring, they even hosted Norman’s preschool-aged son from a previous relationship, and Susan was touched by how tenderly Norman treated him. He snuck the boy his pacifier when Susan tried to wean him off of it, then took everybody out for ice cream when she was eventually successful.

They still used, of course. Because Norman was closer to the source than any of Susan’s previous boyfriends, his stuff was purer, and it took less to get high. Adhering to Jay’s advice, Norman never touched his own inventory; he and Susan consumed only what they’d purchased for themselves. Norman never injected the stuff, and Susan stopped shooting up after the overdose. She used more than he did, but it was fun when they did lines or freebased together, like their own private party out there in the woods. Sometimes they got paranoid — heard voices, saw people lurking in the bushes — but they never got angry or irritable with each other, and they never, ever fought.

If Norman was dealing in larger quantities over time, Susan could only infer it from how they moved product around. Once, Jay and an associate came to Maine in an RV, which seemed to portend a larger deal. Another time, Susan and Norman landed in Boston to find Mike Massey waiting with a tow truck. He and Norman had talked about buying one, but she thought it was to provide the chronically underemployed Mike with some legitimate income — Norman sometimes worried about the Masseys’ kids. Instead, they stashed Norman’s suitcase in the trunk of the rental, then hitched the car up and towed it, lights flashing, back to Swanville. Old-fashioned Maine ingenuity. Who, after all, was going to make them in a working tow truck?

Later, she remembered sitting in the back of that truck, Norman turning around to grin at her from the passenger seat, and the two of them just giggling at the audacity of it all. By then, she was sure that she loved him.

Sergeant Harry Bailey never wanted to be a cop. He grew up in Washington County, married a Washington County girl, and got a decent job as a machinist for the aerospace giant Pratt & Whitney, down in Connecticut. Hell, if it wasn’t for his size, he’d probably still be tinkering with turbines down in Hartford. But Harry was 6’3″ and 240 pounds, with giant mitts, a size 15 shoe, and a nose like a tiny fist in the middle of his face. Like it or not, he oozed the kind of beef-necked authority the Maine State Police were looking for, and for three years, a trooper buddy put an application in his hand every damn time he visited home. Missing Maine, he finally caved and joined the force in 1966 as a patrolman around Belfast.

But despite his intimidating stature, Trooper Bailey was no meathead. He was known to tell colleagues over the years that he thought of himself as a peace officer as much as a law enforcement officer. He had a mischievous sense of humor and a way with people. Harry made friends easily around Belfast — not to mention among other troopers, cops, and wardens, who called him “High Pockets” on account of his height. As Trooper Bailey graduated to Corporal Bailey, he gained a reputation in law enforcement circles for his compulsive work ethic, fearlessness, and close community ties. Once he ran alone into a burning house, looking for occupants, like something out of a movie. Other cops marveled to see him putting in 70- or 80-hour weeks, and he was known to take it hard when, say, he arrived on the scene of an accident to find an acquaintance injured or worse.

But to Harry, this was just the nature of the work. You weren’t punching a clock and playing cops and robbers, he figured. It was a 24-hour job, and the “bad guys” were more or less just like you, capable of turning things around if you treated them with some empathy and respect.

Like it or not, Harry Bailey oozed the kind of beef-necked authority the Maine State Police were looking for.

Still, by the time he made sergeant in 1977, Harry was getting a little burned out. So when the chief of the State Police asked whether he’d be interested in a change of direction, High Pockets Bailey was all ears.

The War on Drugs had come to Maine, the chief told Harry, and drugs were winning. In the late ’70s, marijuana smugglers were targeting Maine’s long and sparsely policed coastline. The Coast Guard could only do so much, the chief said, and the Drug Enforcement Administration’s presence in Maine was limited to two or three guys sharing an office building with a dentist in Portland. So the agencies were banding together, forming an ad-hoc unit comprised of officers from every level of government — from backwoods game wardens to clam cops at the Marine Patrol to a few hardened Feds fresh off the streets of New York and Boston. The State Police needed someone to ditch the uniform, embrace undercover work, and head up their end of the sundry coalition, working statewide with officers from the DEA and other agencies. Harry ran it by his wife, who thought it was too dangerous, so he told the chief he could only commit to a three-month detail.

Thus began nine years as a supervisor of Maine’s Federal-State Anti-Drug Smuggling Task Force. Harry traded his cruiser for a series of unmarked beaters, and at almost 40, he let his hair grow shaggy and sprouted sideburns and a mustache for undercover work. Folks around Belfast learned not to greet him unless he spoke up first, for fear of blowing his cover. Harry became a tireless student of Maine’s marijuana underworld, and his task force was, from the outset, a model of law enforcement cooperation across jurisdictions. In its first year alone, the outfit seized some 100,000 pounds of marijuana coming into East Boothbay, Seal Cove, Little Machias Bay, and elsewhere. In 1980, an elaborate sting operation in Stonington seized so much pot and evidence that Harry ordered a small boat loaded with product to be temporarily stored in his yard, just until some agency could process it. His wife and kids woke up to a uniformed cop at the kitchen table, a dooryard full of evidence, and a front lawn reeking of cannabis.

As the 1980s progressed, not a year went by without Harry and his partners spearheading some headline-making pot bust. He worked closely with Maine’s small DEA staff, rubbing shoulders with biker gangs, ganja-growing cultists, and plenty of Boston mafia types. By 1984, High Pockets Bailey thought he’d seen the worst and the weirdest of what Maine drug smuggling had to offer.

So he was stunned when Billy Christensen showed up, telling stories of a cocaine empire flourishing right under his nose.

Over time, the flights to Miami just kind of stopped. Susan didn’t ask why. All she knew was Norman had a new associate, a guy in Cape Cod named George Munson. Sometimes they’d fly to see him on commercial puddle jumpers from Bangor or Waterville, other times they’d drive or charter a two-seater flight from the Waterville airport. Like Norman, George was from Pawtucket, and he too struck Susan as a serious businessman — none of the strutting or veiled threats that there’d been with Jay. George seemed like the kind of guy who belonged to a country club. He lived with his wife and kids in a lovely home in Hyannis with a great wine cellar. She never saw him use drugs, and the few times he came up to Swanville, Susan thought he seemed out of place — too refined for the woodsy hills around Swan Lake.

Of course, she didn’t know until later that George’s Colombian connections put him about as close to the top of the cocaine supply chain as you could get without leaving the country. And it wasn’t until later that she heard his refined voice on a tape recorder, suggesting none-too-subtly that she be killed.

By the summer of 1984, things were changing back around Belfast. Norman and Susan were starting to realize that some of the people around them were honest-to-God junkies. When they went over to the Masseys’, Mike and his wife would bicker nastily, because she knew he’d been doing business with Norman, getting high without her while she was stuck with the kids. Norman and Susan would sit awkwardly on the couch, sometimes swapping a look that said, “Thank God we’re not like that.”

Things were even worse for Billy Christensen. The guy already seemed perpetually down on his luck, but now he came over to their place instead of the other way around, because he, his wife, and kids were living in a tent. He looked bad — wiry and haggard. His wife would freebase cocaine until she was flat-out immobilized, her eyes rolling back so you only saw the whites, like everything else had been erased. Norman worried about them and tried to “help” by fronting cocaine to Billy and Mike on credit — something he’d never do for anyone else — so they could cut it with talcum powder or baking soda and make extra cash. Billy seemed grateful, in a pathetic way. Sometimes he would hang around the Swanville house offering to pitch in, helping count money or volunteering to take their trash to the dump.

Norman and Susan would sit awkwardly on the couch, sometimes swapping a look that said, “Thank God we’re not like that.”

As the year went on, things changed for Norman and Susan too. It wasn’t just generosity with Billy and Mike — Norman was getting sloppy. Sometimes he’d let Billy or Linwood’s buyers skip the middleman and come by the house, small-time users who just wanted enough to get them through the weekend. Norman and Susan started breaking Jay’s old rule about pinching from their inventory. More and more, Norman traveled alone, and once he left instructions for Susan to sell a quarter-ounce to a friend of Billy’s — something she never did, for a guy they didn’t even know.

One day, Yeller went out and never came back, the yellow Lab that Norman loved, and Susan was stunned to see him truly angry, cursing and pacing in a state of paranoia. Someone had killed him, he insisted, someone had poisoned Yeller so they wouldn’t have a guard dog.

Slowly, the Ozzie and Harriet domesticity that had always set Susan and Norman apart just seemed to dissolve. They were using more, of course — Susan especially. She lost her interest in cooking and keeping house, and Norman stopped treating her with the china-doll adoration that he always had. One night, they were flopped on their sectional sofa, quite high, when Norman complained he was hungry.

“So go get something to eat,” Susan shot back.

There was a silence. “I don’t think I want to be with you anymore,” Norman said coldly. “You don’t make me anything to eat.”

He said it just to hurt her — nothing came of it. But in her increasingly rare moments of clarity, Susan had a feeling that things were tilting out of balance, going askew in some way that her charm couldn’t fix.

That was the feeling she woke up with on her birthday — November 20. She was 26 years old. The night before, she and Norman had tried to charter a flight to meet George in Hyannis, but the pilot was tired, and after arguing with him on the phone, they put it off until morning. They left for Waterville at dawn, a sliver of moon still hanging in the sky as they followed the forested highway out of Swanville, across Dead Brook and winding through the Georges Highlands.

The flight was uneventful and the visit to George’s quick, but Susan couldn’t shake her unease. When Norman stepped out of the room at George’s, she felt hyper-aware of the brown suitcase in his hand, noticing it in a way she never did. That night, at the airport in Hyannis, she started to cry. She told Norman she didn’t want to fly back to Maine.

“You’re just emotional because it’s your birthday,” Norman told her, some of that old concern back in his voice. “It’s going to be all right,” he said. “We’re going home.”

Norman slept on the plane ride back, but somehow, Susan thought, even that looked suspicious. When they got off the plane in Waterville, he touched her gently on the arm. “I’m going to go pay,” he said, and Susan, acting on autopilot, took the suitcase. She’d meet him at the car, she said.

It was well after dark, and Susan didn’t see the DEA cover team in place as she walked out into the parking lot. The two young men tailing her, however, weren’t as subtle. Susan registered their presence and quickened her pace without thinking, acting on instinct. By the time one of them called out, holding up some kind of plastic-coated ID card, she had already opened the back door. She set the suitcase inside, fixed her sweetest smile to her face, and turned around slowly. It was bitterly cold out.

“I’m a DEA special agent investigating a drug crime,” one of the plainclothes men announced. “We’d like to ask you some questions.”

Billy Christensen gave up Susan and Norman. What else could he do? He had been in trouble before, he told Harry, but never like this. He had never feared for his life, for his kids’ lives. He was beyond rock bottom. Billy needed help. And the only cop he trusted was Harry Bailey.

Harry was stunned by the stories Billy Christensen was telling. He’d known this kid since he was a teenager, knew his family over in Liberty. Billy had a bad track record, sure, but he wasn’t a hardened criminal. He was like a lot of midcoast and Down East guys — a part-time logger and full-time opportunist. He’d sold some grass here and there, a little LSD, and when he was real hard up, he and his brother would steal manhole covers to sell for scrap. Harry had busted Billy a few times over the years for some minor drug stuff, but he always treated him well. Here was a decent guy who made some real dumb decisions, Harry thought.

Now here was Billy, telling Harry he’d lost his house, hooked his wife on coke, and was in to some Colombian dealers for nearly $90,000. If he didn’t pay up on their next visit, they said they’d take one of his eyeballs instead. Billy looked like a damn skeleton, and he couldn’t sit still. The guy was a dead man walking, in more ways than one.

At first, Harry wasn’t even sure he believed him — hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of dollars worth of coke being trafficked through the midcoast boonies? This was where Harry lived, for crying out loud. Portland had some troubles with coke dealers coming and going, sure, but Harry had been on the drug beat for seven years, and the biggest product peddled north of Casco Bay had always been pot. Now Billy Christensen turns up, talking about five-digit coke deals at the Bucksport mill, Colombians crashing in Route 1 motor lodges, and cash piled up in doublewides like something out of Scarface. Some guy on a dead-end road in Swanville — Swanville, for God’s sake — was flying it in on chartered planes.

To Harry’s partners at the DEA, the sudden emergence of informant Billy Christensen came as the best kind of shock. It was like someone had gift-wrapped a drug dealer Rolodex for a cartel they never even knew existed. The Belfast Police Department, it turned out, had been looking into Norman Grenier, but Billy’s connections were broader. To hear him tell it, the coke-smuggling scene around Belfast was far from linear. He bought and sold for Norman, yeah, but he also sometimes bought directly from Colombians from Central Falls, Rhode Island. He’d bought straight from George Munson before too, as had Linwood Jackson. Linwood might buy a pound from Norman one week, then get it straight from the visiting Colombians the next. Billy had bought from the same people he’d sold to. It was a tangled web, all depending on who was holding. And Billy knew everybody.

The DEA agent assigned to the case was Wayne Steadman, a one-time science teacher who came to Maine as an agent in the mid-’70s and was one of the first to sound the alarm about Maine’s vulnerability to smugglers. Wayne and Harry debriefed Billy. As the summer of ’84 slid into fall, they hatched a plan: Accompanied by an undercover cop, Billy would keep making deals around Belfast, gathering evidence on as many dealers and users as possible, targeting “big fish” like Norman, Linwood, and the Colombians. Gradually, the task force would start to pick up the dealers, and with Billy’s accrued evidence, try to “flip” them, working their way up the supply chain while cleaning up the glut of small-time operators on the midcoast.

At first, Harry wasn’t even sure he believed him — hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of dollars worth of coke being trafficked through the midcoast boonies?

The task force rented a two-story house on Congress Street in Belfast and installed Billy and his family on the ground floor. To be believable as the Christensens’ coke den, it had to be a dump. The DEA had to put in a new furnace and reinstall a disconnected phone line, which they also bugged. They got a judge to approve the installation of microphones in the walls and a closed-circuit television system — something law enforcement in Maine had never done before. On the top floor, they set up a monitoring station with its own back entrance. In the kitchen, a ratty tapestry hid a hole in the wall through which the team upstairs watched and recorded via a small video camera. Nearby, a second rented home served as a command center.

Norman was a target from the get-go. Harry and Wayne coached Billy into gathering the kind of evidence that would help them build a conspiracy case. Billy brought them bags of trash from the Swanville house, and once, when Norman was away, he took an undercover state police officer to buy coke from Susan, so the cops would have something on her too. Of course, he filled in Harry and Wayne on Norman’s trips to Cape Cod.

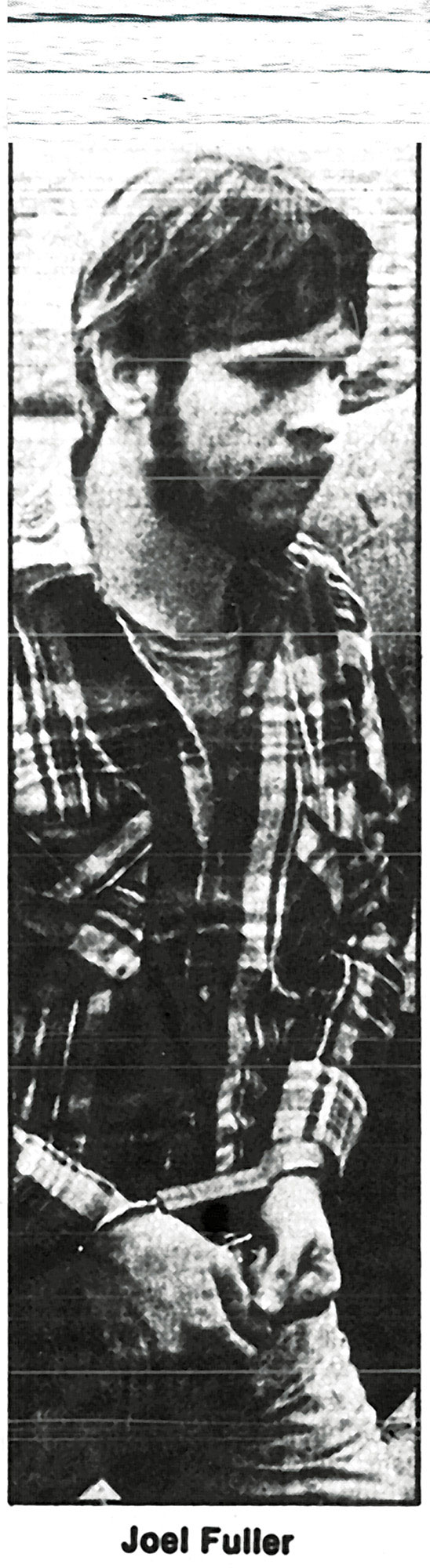

Billy was still an addict, though, still using while he sat with dealers in his new apartment or a motel room somewhere. Wayne and Harry knew the guy was probably still managing to bring home coke, but they couldn’t monitor him 24/7. The family still had a right to privacy, and they only ran tape when a deal was going down. If there weren’t arrangements to bring a dealer to the house, they might not even have guys upstairs. That was the case the night Joel Fuller showed up.

On December 12, Billy opened his door to find Fuller and a few of the local good old boys standing outside. A small guy with a rough beard and a piercing stare, Fuller had cut wood with Billy here and there, and Billy knew he was trouble. A local poacher who ran with Linwood Jackson, Fuller had a reputation as an outlaw type, somebody who’d do anything for a buck. He asked Billy where he might find this guy Norman Grenier.

Fuller had read in the papers that Norman and Susan had been busted in Waterville. He figured a hotshot coke dealer was bound to have some cash on hand — and unlikely to run to the cops if somebody shook him down for a few stacks. Billy tried to talk him out of it, warning that Norman was armed, but Fuller just laughed and flashed a sawed-off shotgun tucked into his pant leg.

When Fuller drove off with his buddies, heading for Swanville, Billy grabbed the phone and tried calling Norman to warn him. But when he dialed, all he heard was a shrill, empty tone. The line at the Swanville house was dead.

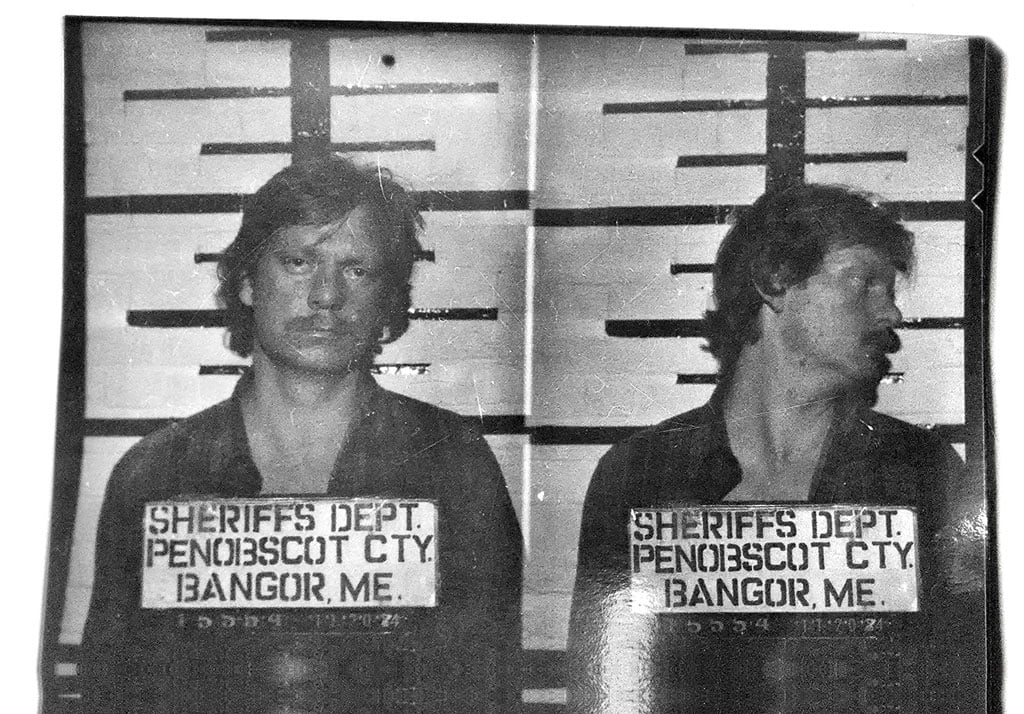

Norman’s brown suitcase contained $13,000 and 1½ pounds of high-grade Colombian cocaine, with a street value somewhere north of $50,000. Of course, Norman and Susan lied at first, but the DEA obtained a warrant to open the bag, and they spent a night in the Penobscot County Jail before going in front of a federal judge. When they were released on recognizance, Susan’s dad picked them up at the Bangor courthouse. He was a former Border Patrol agent and one-time deputy sheriff. Susan had hardly seen him in two years.

“So this is the mythical Norman,” was all he said, and he drove them back to Swanville. If her family had wanted to call and check up in the ensuing weeks, they couldn’t have, because Norman, out of caution or paranoia, had cut off the phone line months before.

They binged on coke right after the arrest, then made some attempts at getting clean. In early December, they were formally indicted and an arraignment date set. They met with lawyers and a probation officer. Unknown to Susan, Wayne Steadman took Norman aside at one meeting and tried to flip him. Think about cooperating, Wayne said, and we can make some recommendations about your charge. Norman said no.

In the days that followed, Norman seemed tired, defeated. They had him, and he knew it. There was no talk of beating the charge, no talk of running. Norman was going to prison, and he promised Susan that, somehow, he would be the only one to go. They were lying on the couch one night when Norman suddenly looked up at her, as if having a realization.

“I have to take care of you,” he said, his dark eyes more somber than ever. “I have to buy you a really great Rolex or something — something you can always sell one day if you need money.”

On the night of December 12, they were on the couch again, watching a movie on VHS. Susan was in a bathrobe that used to be her mom’s. The first thing they saw were the headlights coming through the big picture window behind the sofa, and both of them startled.

Norman’s brown suitcase contained $13,000 and 1½ pounds of high-grade Colombian cocaine, with a street value somewhere north of $50,000.

When Susan looked out, she saw a man in the passenger seat wearing sunglasses. But the car made a Y-turn in their cul-de-sac, and they watched as it drove, slowly, back down the hill towards the main road. Susan and Norman waited a while, hearts beating with junkie adrenaline, before exhaling and turning back to the movie.

The noise of the picture window shattering behind them was deafening. Susan screamed as she felt the glass raining down, leaving a barrage of tiny cuts, and she instinctively pulled a blanket over her head. As she curled into a crouch, she felt Norman leap up from the sofa. He kept a shotgun in the bedroom, she knew, and maybe he was going for it. Who knows? Norman never had a chance. Joel Fuller had an itchy trigger finger, and his shotgun went off within a split second of the window caving in. It almost seemed like an extension of the same sound.

A blast of buckshot to the back, from a sawed-off 12-gauge at point-blank range. Poor Norman was dead before he hit the floor.

Susan heard a voice yell, “Stop!” and then another saying, “Hold her!” Or maybe it was the same voice. She felt footfalls on the couch, heard them briefly on the hardwood floor, then felt them on the couch again. And then, silence. Not even the sound of a car peeling away. She stayed stock still underneath the blanket for a very, very long time.

The first thing Harry thought when he heard about the murder was, “My God, the Colombians are onto us.” They knew somebody was talking, Harry figured, and they’d come to snuff out a few hayseed Mainers who knew too much. He contacted Billy immediately, who told him about Fuller.

In the coming days, Harry, Wayne, and the rest of the task force decided it was time to bring in as many dealers and buyers as possible. They couldn’t be sure that Norman’s death had been a robbery gone wrong — it was several days before one of Fuller’s accomplices was arrested, and Fuller himself evaded capture in the woods for nearly a month. Regardless, the Belfast area was suddenly radioactive. They’d lost a major dealer who they’d hoped to flip. People would turn cautious. They needed to capitalize on the work they’d already done.

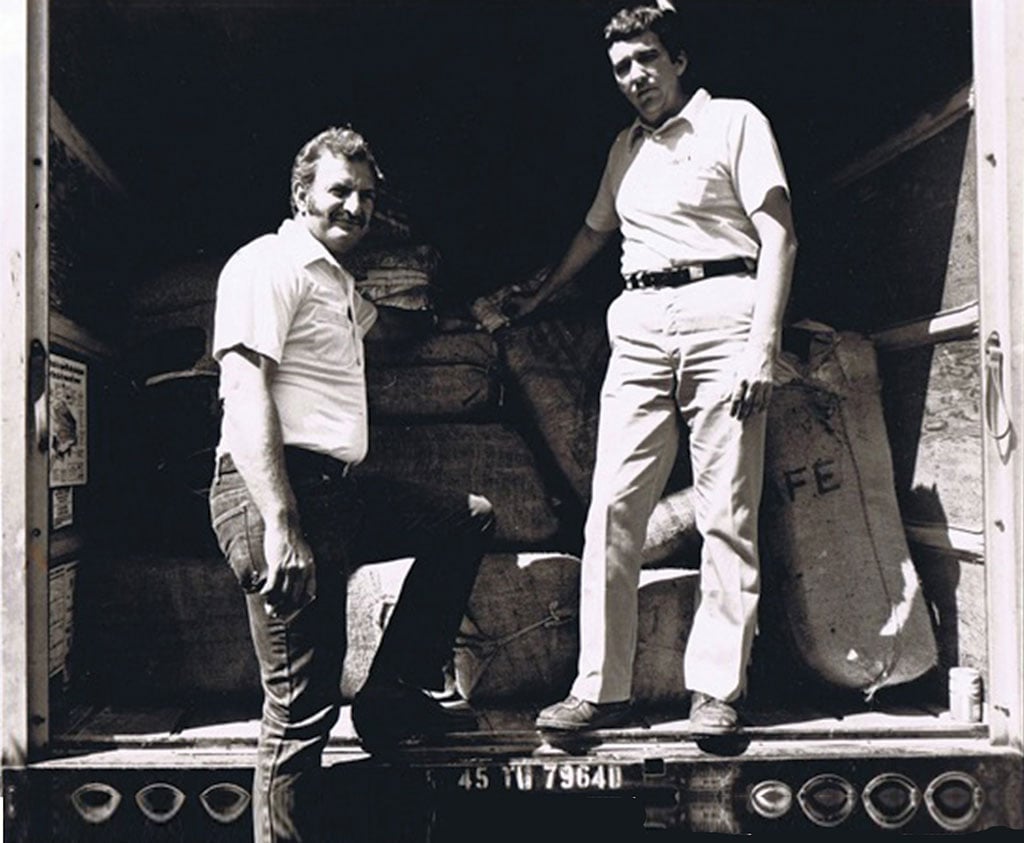

On January 10, 1985, Wayne sat upstairs on Congress Street, watching on a video screen as player after player in the Belfast cocaine underworld stopped in at Billy’s to make buys. Harry watched the comings and goings from a parked car. At nearby intersections, city and county police were stationed to tail buyers as they left, pulling them over far enough from the house to be inconspicuous. It was an elaborate sting with upwards of 30 officers involved, and it went off without a hitch. The task force nabbed 18 people by suppertime — some low-level dealers, a few mid-level guys, and two Colombian couriers from Central Falls. It was a Friday. Over the weekend, after pressing the first batch for names, they brought in seven more.

By Monday morning, Billy Christensen and his family had disappeared into the federal witness protection program. New names, new location, new lives. Of those he’d put in jail and otherwise left behind, only Susan Pierce ever heard from him again.

[cs_drop_cap letter=”S” color=”#000000″ size=”6em” ]usan woke up in Clinton on January 11 and heard about the bust from her dad. Her lawyer had called, he said, and she had to go to Bangor to turn herself in — in addition to Waterville, she was now being charged for having sold to Billy’s undercover “friend” months before.

It was weeks after the murder when she and her lawyer went back to the Swanville house. Norman’s blood was still dried up on the floor. Her parents had sent a moving van, but she collected a few stray things and refreshed her memory for future testimony. Inside the bedroom closet, she noticed a brown paper package stashed discreetly atop the door frame, something Norman had planted there.

It wasn’t a Rolex: It was $19,000 in cash. She gave the lawyer $9,000 and kept the rest.

The week after the Congress Street sting, Maine’s U.S. Attorney called a press conference to announce that, from that moment on, investigating cocaine smuggling would become his office’s number-one priority. “Although the task force has foiled numerous drug deals in its history,” the Bangor Daily News wrote, “none have brought the dealings of the cocaine underworld home to Maine in the way that the Belfast operation has.”

Over the next couple of years, the Belfast sting led to dozens of convictions for trafficking and possession. Susan cooperated with the U.S. Attorney’s office. Her testimony helped to convict both Jay Hart and Cape Cod kingpin George Munson.

In July of 1985, just before being sentenced, one of the dealers arrested at Congress Street was found dead of a 12-gauge shotgun blast. He had agreed to testify against Linwood Jackson. Joel Fuller was out on bail at the time, awaiting trial for Norman’s murder. He was later convicted of both killings. Jackson was convicted anyway and has since died of cancer. Fuller is currently serving life in Maine State Prison.

Harry Bailey retired from the Maine State Police in 1986. He served three terms as a state legislator and spent most of the next 30 years running a sporting camp in Grand Lake Stream. Last June, he passed away at age 73. In 2006, Harry was named a Legendary Trooper, although he was always quick to credit teamwork for the many accomplishments of his motley task force.

One of Harry’s final acts as a police sergeant was to visit Maine high schools, speaking about the dangers of drugs. His speaking partner on such trips was Susan Pierce, who got clean, stayed clean, and never served time. Thirty years later, she still gets choked up talking about Harry and the other cops and lawyers who helped her pull her life together.

One day, maybe a year after the Belfast bust, Susan was sitting in the office of an assistant U.S. attorney when his telephone rang. On the line was the man who used to be Billy Christensen, the man who had betrayed Norman. Did Susan want to speak with him?

When she took the receiver, she heard Billy’s voice on the other end — wavering and full of emotion, but recognizable.

“Hi, Susan,” he said quietly. Then he hesitated. He sounded scared.

“Billy,” Susan said. “I don’t blame you. I’m not mad at you, and I don’t blame you.”

On the other end of the line, she heard Billy break down. Thank you, he said through sobs, again and again. Thank you. I didn’t know what else to do.

“I know,” Susan said, and it felt good to say it. “I understand. You didn’t have any other choice.”

And then, for a while, the two of them just stayed silently on the line, neither one wanting to speak or hang up.