By Elizabeth A. De Wolfe

From our June 2015 issue

It was in Saco — that riverside den of iniquity — that Caroline first began her descent into wickedness.

She’d been such a good girl when she first arrived: a plucky 13-year-old seeking work in the city’s booming textile mills, a pious churchgoer, a loyal daughter to her mother and father back home on the farm. But the farm couldn’t hold her. The year was 1848, and for Caroline and thousands of “factory girls” like her, work in the textile mills of Saco and Biddeford, weaving cotton into fabric at $3.25 a week, represented a ticket to middle-class prosperity. In the mid-19th century, Saco and Biddeford were among the richest, most populous, and most cosmopolitan cities in northern New England — fine places for a girl of marriageable age to attract a suitor.

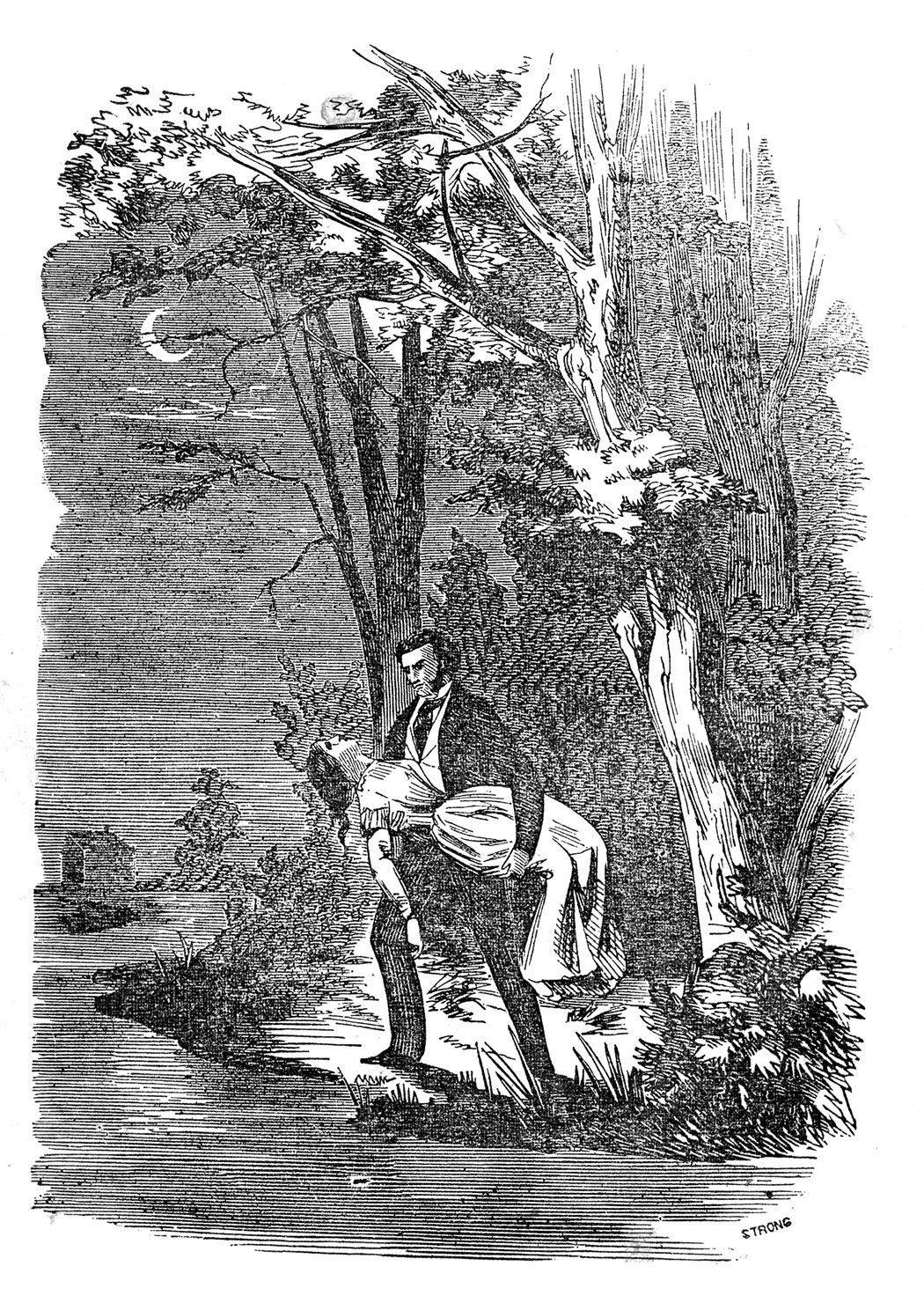

Caroline attracted Henry, a charming older carpenter smitten by the young girl’s persistent attentions. Her parents didn’t approve of their courtship, but the increasingly willful Caroline — intoxicated by her own independence — ignored their reproach. When they threatened to remove her from the mill if she continued her relationship, Caroline saw Henry in secret. On Sunday mornings, she skipped church to join him for dreamy boat rides down the Saco River. When he urged her to elope with him to Boston, she agreed, and when he demanded she demonstrate her love on the night before their supposed wedding, she gave herself over to his carnal desires.

The next morning, Henry was gone — as were Caroline’s money, watch, clothes, and even the rings on her fingers.

Ruined, destitute, and robbed of her honor, Caroline turned to the streets. She descended into prostitution, became wracked with disease, and hobbled the alleys of New York City for the remainder of her short and pitiful life. The moral of Caroline’s tragic story? “Never deceive a fond mother.”

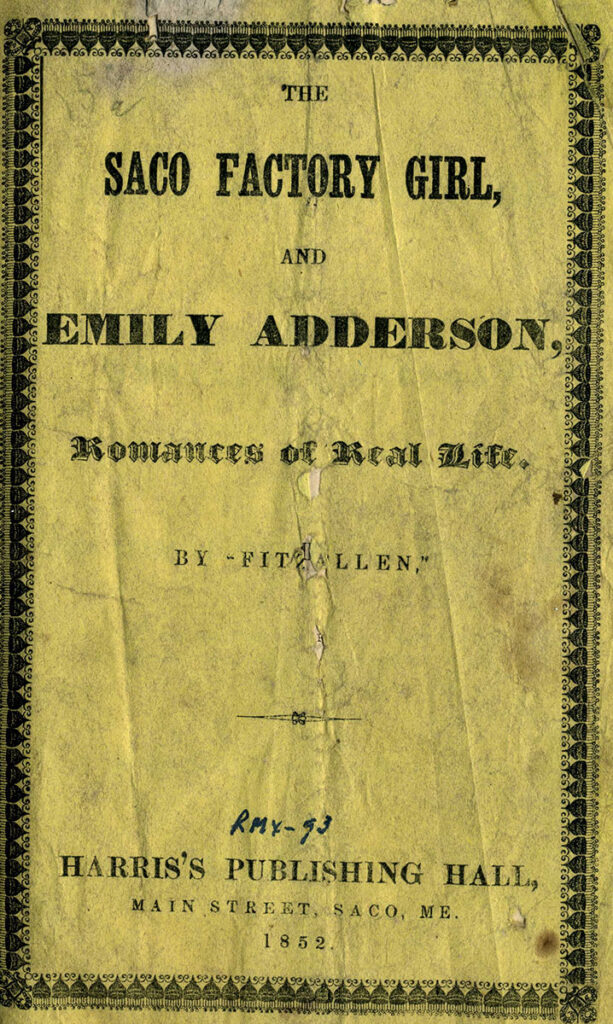

So wrote a mysterious author known only as Fitzallen in The Saco Factory Girl, a titillating novella published in Maine in 1852. For a short stretch of the mid-1800s, the factory girls of Saco-Biddeford played starring roles in their own popular sub-genre of pulp fiction, birthed by the twin cities’ overnight economic success. The tales gave eager 19th-century readers a peek into a forbidden world of sex, sadism, and sin — but, ahem, only to warn against such behavior, of course. And though they’re all but forgotten today, the stories exposed a discomfort with women in the workforce that we have yet to fully shake.

“Progress is the order of the day,” declared the inaugural edition of the Saco-Biddeford city directory in 1849. Since the textile mills had arrived in 1833, the metro’s population had doubled to nearly 12,000, hundreds of new businesses had opened, and some 23 new streets had been laid out across the rapidly developing twin cities. Nestled on the shores and islands of the Saco River, the textile factories had turned a rural agricultural backwater into a bustling urban center — so large, by Maine standards, that it suddenly required its own directory, listing all of its citizens’ residences and occupations. For more than 2,700 young women in that first edition, that occupation was “textile operative” — or factory girl.

The Saco-Biddeford factory girls were the daughters of New England farmers: Protestant, white, and looking for work in the years between childhood and marriage. A generation before, they’d have stayed home, spinning thread and making candles, but factory-made goods had rendered such domestic tasks obsolete, and for a farming family, an unwed daughter in her teens or twenties was an economic drain. Millwork was an opportunity for these future wives and mothers to build a nest egg, and in 1850, they made up some 80 percent of Saco-Biddeford’s factory workforce. In some ways, they were ideal employees: managing looms took attention to detail rather than physical strength, and farm girls were nothing if not diligent. Raised to be dutiful and submissive, they took orders well. And of course, the mill owners profited by paying them far less than their male counterparts.

In self-congratulatory tones, Saco-Biddeford’s tycoons, newspaper editors, and city fathers lauded these young women, whose fleet fingers turned 6 million pounds of cotton each year into more than 25 million yards of fabric. For the women, the payoff for tiring, 12-hour workdays was a rare taste of independence, an opportunity to earn and spend one’s own money. Even after paying $1.25 for weekly room and board (at company-owned boardinghouses), the factory girls had cash in their pockets, and Saco-Biddeford’s booming stores eagerly catered to them: Hamilton & Company offered the latest bonnets, silks, and shawls; George W. Shannon & Company advertised ladies’ dresses in every fabric. Factory girls bought hair ribbons, cheap jewelry, candy, and magazines. They posed for daguerreotype portraits and attended plays and lectures. Saco-Biddeford was on the cutting edge of a national experiment in women’s economic freedom.

But not everyone saw the changing social roles of the factory girls as a reason to celebrate. Local ministers chastised young women for their vanity and spendthrift ways. In sermons and newspaper editorials, the pious took factory girls to task for indulging in self-centered pleasures. Weekly advice columns “For the Ladies” cautioned girls against transient male workers and “dandy-jacks” with gold chains, recommending farmers and mechanics as more suitable future mates. To many in the conservative middle class, the notion of women delaying or even foregoing marriage for work or higher education represented a threat to society’s very stability.

Such disapproval found a voice in a dozen or so novellas, short stories, and poems published between 1849 and 1854, which made tragic protagonists out of the Saco-Biddeford factory girls. The books weren’t much longer than glorified pamphlets; they were cheap, hurriedly produced, and designed to grab a reader’s eye with bright-yellow paper covers (at the time, a common means of signaling a lurid read). They had absurdly long subtitles with buzzy adjectives, a bit like today’s Internet clickbait: “Giving a Thrilling History of Four Years of the Life of a Factory Girl, From the Time She Left Her Father’s House at the Age of Thirteen, Until the Age of Seventeen Found Her a Ruined Female in New York City.” Some were murder mysteries and others romances, but none were destined to be great works of literature. Centered on naïve young women and the cads who sought to deflower them, these melodramatic tales of courtships gone wrong were one part trashy romance, one part moralizing sermon on factory girls’ behavior.

The tales gave eager 19th-century readers a peek into a forbidden world of sex, sadism, and sin — but, ahem, only to warn against such behavior, of course.

Such stories were part of a broader 19th-century trend of “sensation fiction” about single girls in the workforce, women who paid the price for breaking with social and sexual norms. But they were decidedly local tales too, filled with references to Saco-Biddeford’s mean streets and well-known Maine landmarks. In one, a pair of lovers meets for trysts at Wells Beach. In another, Biddeford Pool provides the setting for an overnight rendezvous. Their authors were typically “hack” writers, paid cheaply by publishers to dash out thrilling sagas ripped from the headlines. Pen names with an aristocratic ring (like “Fitzallen”) or fake titles (like “the Reverend Mr. Miller”) gave a sheen of moral authority.

And while the cotton factories gave the books their social backdrop, the factory-girl tales rarely said much about life in the mills. Textile production was dangerous work, with fast-moving machinery that could entrap a worker’s limbs, fiber-filled air that caused respiratory ailments, and the threat of flash fires that turned workrooms into infernos. But to sensational authors like Fitzallen, the bigger threat was outside the factory walls, when young female workers strolled about town after hours. There were men out there, men who might take advantage of an independent woman, away from her parents’ and neighbors’ protective eyes. The real danger was misguided love, and the moral of the Saco-Biddeford tales was clear: young women and self-reliance were a bad mix. Girls who left their parents’ care risked their purity and their marital possibilities — even their lives.

If there’d been an Oprah’s Book Club in 1850, Mary Bean: The Factory Girl would have been on it. The story was loosely based on the life and death of one Berengera Caswell, a New Hampshire factory girl who followed a former lover to Saco in 1849. Caswell was pregnant and unmarried to the father, a Biddeford native and millworker named William Long. After finding him in Maine, Caswell sought an abortion — legal at the time — but she died from complications, and the resulting trial of the doctor who’d administered the procedure scandalized the state.

During the trial, Caswell was described alternately as a friendless victim and a self-indulgent wastrel, bouncing from mill job to mill job, wasting her money on leisure and comforts — her very independence was appalling to some 19th-century bluenoses. Long was painted as a cad. The abortion doctor was convicted, but his sentence was eventually reduced to manslaughter, and he served just two years.

In Mary Bean, an author known only as “Miss JAB of Manchester” put a fictionalized, tabloid spin on the story, playing on the anxiety of parents and the tawdry interests of the masses. The book was published even before the case came to trial, sold at train depots and newsstands for twelve-and-a-half cents. It was a “domestic story of thrilling interest,” promised an ad in a Saco newspaper, and it “should be read by every young lady and gentleman.”

Such ladies and gentlemen would learn of the beautiful Mary Bean, the “nearest approach to perfection . . . at whose shrine of beauty and loveliness many an amorous swain ardently desired to offer up his heartfelt devotions.” Mary is a stable young woman with a fiancé and a bright future — until the handsome George Hamilton returns to their village, entrancing her with glamorous tales of business success amid the mills of Manchester, New Hampshire. She leaves home with the debonair George, trusting his assurance that they will wed. In Manchester, Mary takes to factory work. When she presses her beau for a wedding, however, he coaxes her to sleep with him first. She is seduced — and then, of course, abandoned.

When she discovers she’s pregnant, Mary tracks George to Saco, but the scoundrel brings her to a shady abortion doctor, and she’s never heard from again. Meanwhile, Mary’s “not so attractive” sister, Ellen, stays at home and marries her sister’s original fiancé. Mary, says Miss JAB, “should have paused-reflected-and decided according to the dictates of her better judgment. But no; she was rash and precipitate, and now she reaps the bitter fruit.” Ellen keeps a portrait of her dead sister in her parlor, draped with a black cotton crape of mourning. Oh, the touch, the feel, the tragic irony of cotton.

Some antiheroines came to slightly better ends. The title character of “Emily Rollins, or, the Factory Girl of Saco: A Tale of Romance,” serialized in 1849 and 1850 in the Biddeford Mercantile Advertiser, is a beautiful orphan who works in the York Manufacturing Company mills. After work, Emily retreats to her rented room to care for her ill grandmother. But she has also stolen the heart of the wealthy and dashing Abraham Fellows. He is conveniently on hand to rescue her when a terrible fire consumes Emily’s lodging — and alas, her grandma, whose charred arm bone is retrieved from the rubble, shown to Abraham, and later, in a rather macabre twist, encased in a glass coffin as a memorial. Emily faints and loses her reason, but she regains it and marries her suitor. Her dutiful attention to family earns Emily a happier ending — all except for that arm bone.

Some Saco-Biddeford tales’ plot twists would put Days of Our Lives to shame. Fitzallen’s 1852 follow-up to The Saco Factory Girl (called The Biddeford Factory Girl and subtitled, “Being the Most Thrilling Narrative Ever Published”) begins with — wait for it! — a young girl ignoring her parents’ advice. Ada Richardson leaves her boarding school for a job in the Biddeford cotton mills, meets a handsome man, and elopes. This one doesn’t abandon her! Instead, he dies, and soon Ada is alone, alienated from her parents, and vulnerable.

Ellen keeps a portrait of her dead sister in her parlor, draped with a black cotton crape of mourning. Oh, the touch, the feel, the tragic irony of cotton.

When she is — wait for it! — seduced and robbed by a con man, Ada swears revenge. In a weird and certainly dated twist, she puts on blackface, pretends to be a man, and becomes a servant to her swindler — all while teaching herself to gamble at cards. She eventually out-cons the con man, winning back her money, but not before learning that her sister has been kidnapped by the con man’s associates. She rescues her sister, who was about to be — wait for it! — seduced by her kidnappers, then returns, triumphant, to be reunited with her parents. Except that Ada is still disguised as a black man, and when she reveals herself, her parents drop dead from shock.

The moral of this absurd and juicy tale is the same as all the others: Nothing good ever comes from disobeying your parents and moving to Saco-Biddeford.

[I]ronically, the Saco-Biddeford factory-girl tales were eventually condemned by the same moral authorities whose disapproval of the factory girls had spawned them in the first place. In 1850, the editor of the Portland Transcript objected to this “depraved taste for murderous reading” and called out local publishers who pandered to their patrons’ “daily stimulus.” The same year, in the Saco paper The Maine Democrat, the Reverend E.P. Rogers spoke for many when he denounced “the miserable trash which is inundating every community and enervating and dissipating the minds of our youth.” Reading such works, the reverend concluded, would lead only to an “aimless, frivolous life.”Some speculated that the books caused the very behaviors they were (ostensibly) meant to condemn. When a former Biddeford worker with the suspiciously perfect name of Catherine Cotton leapt into a mill canal to drown in 1853, friends speculated that she “must have been reading some romantic or melancholy book” — this, meta-ironically, according to a romantic and melancholy book about Cotton that came out a few months later.

In the end, the factory girls’ growing independence and grit helped bring an end to the era. By 1855, the first generation of textile mill operatives, those formerly meek New England farmers’ daughters, were organizing and agitating for shorter days and better pay. In the face of their female employees’ increasingly forceful demands, Saco-Biddeford mill owners looked elsewhere for labor and found it in immigrants. Greeks, Irish, and French Canadians took those jobs, a new pool of young women destined for working-class lives. With their own daughters safely returning to hearth and home — and not nearly as concerned about the new workers’ fates — middle-class moralists soon lost interest in factory-girl fiction.

For the easily titillated, there were plenty of other yellow-wrapped stories to peruse. The factory girls gave way to imperiled shop girls in even bigger, more dangerous cities; to naïve country girls kidnapped by white slavers; to college women cruelly deceived by lecherous classmates — right up to today’s tales of Facebook frauds and Internet predators. Saco-Biddeford may no longer be the bogeyman, but in a sense, the moral for young girls remains the same: there’s no place like home.