By Michael Colbert

From our October 2022 issue

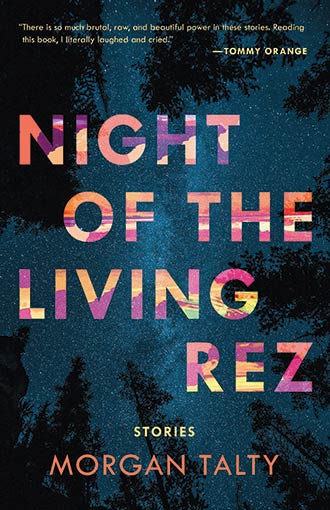

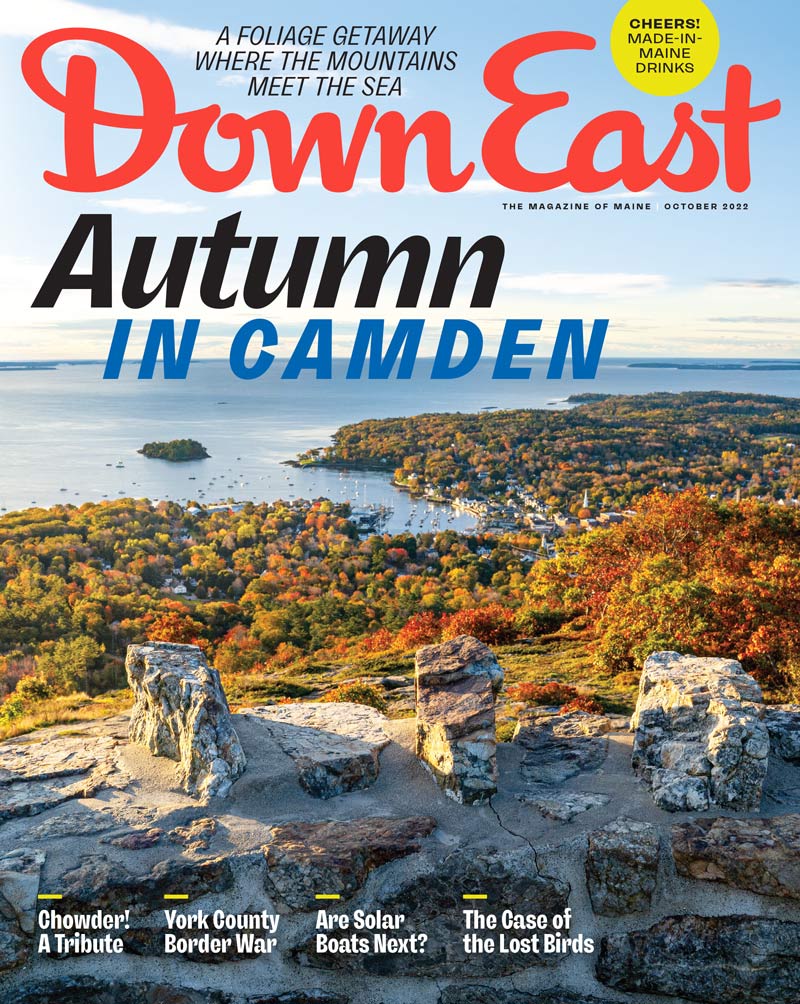

Morgan Talty, the 31-year-old author and Penobscot Nation citizen, didn’t anticipate his debut story collection, Night of the Living Rez ($16.95; Tin House), landing on major booklists. Neither did he expect that the New York Times would call his voice “electric” and commend his channeling of “grief, trauma, boyhood, and brutality in their totality.” But Talty’s crystalline prose — he cites Denis Johnson and Anton Chekhov as major influences — warrants all the praise it gets, with its beautiful rendering of family relationships and the natural world in versions of where he grew up, around the Penobscot Nation’s Indian Island reservation (“The Island,” in fictional form) and neighboring Old Town (“Overtown”). An undercurrent of dark humor ripples through the pages too: in one story, the narrator comes home from buying weed and finds his friend stuck with his hair frozen in the snow, while in another, he’s charged with looking after his newborn nephew but finds himself debilitatingly afraid of the sun swallowing the earth. Recently, as Talty started a new job as an English professor at the University of Maine, he took some time to reflect on the power of place, writing process, and telling indigenous stories.

How are you feeling about all this acclaim?

It feels good. My approach is always that I’m not going to expect much from something, especially publishing a book. I thought this book would be a stepping stone, but it’s been more of a larger bridge. There was that element of luck too that I think also played a role. You can do the work, but will the world receive the work in the way that the work deserves to be received?

What did you import from the real world into this imagined one?

Everything that I recognize as being part of the landscape of Indian Island, Old Town, and the Penobscot River is in the book, plus things I imagined: The tribal lumberyard, which is mentioned as being at the heart of the reservation, is not a thing. Ralph Nelson’s land full of junk with the sweat lodge in the middle is not there. But the place where the boys have their battle [a version of hide-and-seek they play with sticks] is a real place. The only thing I avoided doing was giving any size proportions of the place because I wanted to write more and build on this place. I treat places as I would a character. I feel as if they’re very much alive. Place affects character in a lot of ways. Growing up, I was always outside, I was always in the woods, and so I could not imagine writing characters who are not in a landscape like this.

How did you arrive at a structure of interwoven short stories?

By pure accident, and maybe intuition, and I think respect for the idea of story. If there were no human beings on this planet, story would still exist, there would still be the ability for stories to be told and seen and witnessed, but by whom is the question — the animals and the earth. I don’t think story is something human beings invented; it was there, and we found it. At a certain point when I’m drafting something — this sounds New Age-y or whatnot — I really feel like I’m communicating with this other thing. I don’t like to plot or plan anything because I feel like I need to figure out what the story wants. It’s sort of like this collaboration. I’m collaborating with art, in a sense. I feel like every writing project requires its own approach. I don’t think I would be a writer if it was the same thing over and over and over again. I like to be surprised by the process.

The title story is about storytelling, with an unwanted documentary-film crew out to record life on The Island. What’s the bigger picture of how Native stories get told?

I’ve spoken about this idea of the performing Indian a couple of times with Chelsea T. Hicks [of the Wazhazhe nation, from the Great Plains], whose debut book, A Calm and Normal Heart, just came out. Readers or viewers expect there to be this indigenous image that matches what they think indigeneity is and what they’ve been told it is. You go to Google Images and you type in Native American, and 80 percent of the photos are Plains people with full head regalia, not someone who looks like me, and so I tried to make [that title story] the thing I was detesting. I was trying to make it performative but in a way have it critique itself. Ultimately, this book is a small fragment of the stories I hope come out of the Penobscot Indian Nation — just a sliver of a larger narrative that hopefully will emerge.