By Peter Andrey Smith

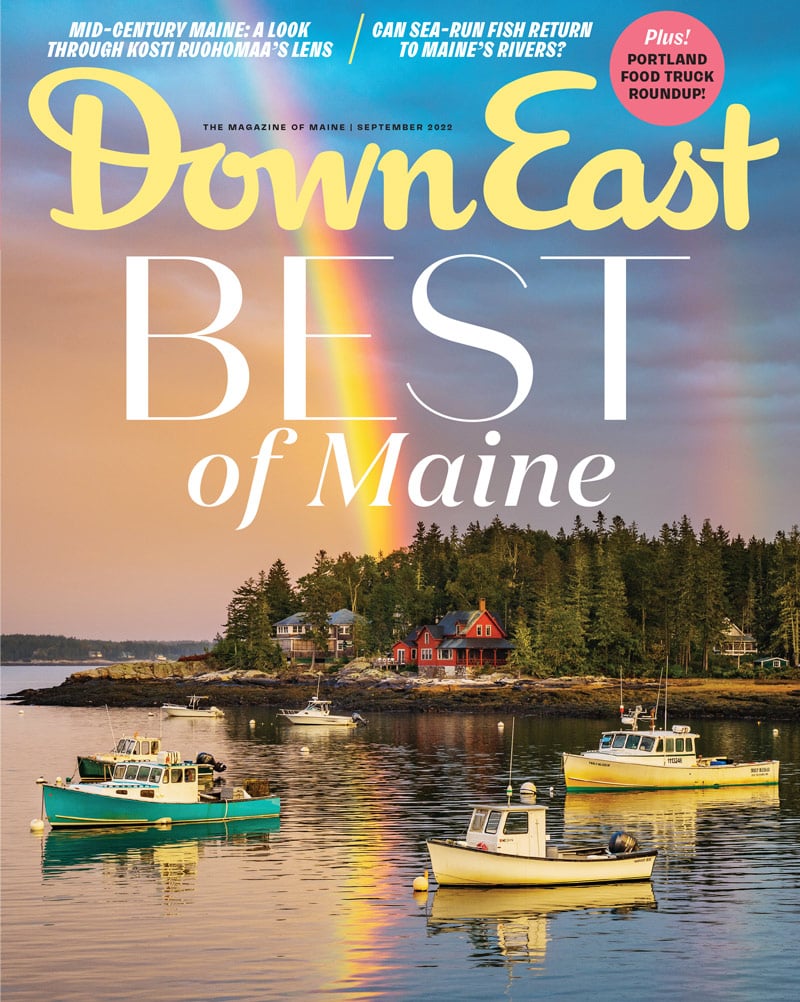

Photographed by Dave Waddell

From our September 2022 issue

On an overcast morning, in the midcoast town of Arrowsic, a group of researchers walked along an old Jeep trail in the Holt Research Forest, wearing hard hats that didn’t much protect against the clouds of mosquitoes. In a fenced-off enclosure, one researcher placed a wooden stick on the ground, measuring out from a flag marker.

“Red maple, class 1,” she said. A seedling.

She moved the stick counterclockwise.

“Three more class 1 red maple.”

“Class 4 red spruce.”

Another recorded each observation on a clipboard, as part of a study on forest regeneration and white-tailed deer. The fence kept deer out entirely, while 280 saplings planted outside it had been treated with a deer repellent. Another set of nearby trees, the control group, was neither fenced nor treated.

That study represents one small piece of the long-term ecological research that’s been playing out across 100 acres of the Holt forest for the past 40 years. In 1980, the Holt family, which kept a rustic summer getaway on the property for several decades, created a foundation to support University of Maine research there. Since an initial survey, in 1982, every tree more than 9.5 centimeters in diameter has been tagged and, at regular intervals, measured — some 32,000 trees in all, providing the highest-resolution data of its kind in the state.

Jack Witham, a scientist with UMaine’s Center for Research on Sustainable Forests, came to know nearly every square inch of the site. He lived in a cabin on the Holt property for 35 years and, with his wife, raised two daughters there. The research forest’s mission was as wide-ranging as his interests: studying forest ecology means observing plants, mammals, birds, and all their complex interplay.

Last year, though, Witham retired, and the nonprofit Maine Timber Research and Environmental Education Foundation (or Maine TREE) took over management of the property. The group plans to build upon Witham’s exhaustive data sets, but they’re shifting focus to research that’s more explicitly useful to woodlands owners — 90 percent of Maine’s woods are privately held. “Being able to zoom in on 100 acres where you intensely study things is not common,” Maine TREE executive director Logan Johnson says. “I don’t know of any other forests that have done 100 percent inventory.”

Witham still keeps tabs on the goings-on, and as he walked with Johnson through the woods to the Back River, they passed a trail camera that monitors for deer and small mammals, then passed orange flagging tape marking a seed trap that collects a representative sample of acorns, pine cones, maple whirligigs, and the like — both of those projects began during Witham’s tenure. The two men stopped in a clearing. Portions of the forest have been cut in the course of the decades, for the sake of seeing how trees grow back. The first cut, in 1988, used a traditional skidder. The second, last year, used a high-tech harvester. Since that most recent harvest, many maples resprouted, as did witch hazels, but oaks appeared to be suffering from the impact of deer as well as a species of small, red, foliage-eating beetle, the oak leaf-rolling weevil. Witham plucked a leaf with a distinctive black cylinder on it — a weevil’s nest, he said.

Witham talked about what else researchers had observed over the years. The effects of agriculture, for instance, persist long after farmland is abandoned. The northern half of the forest, which had been farmed, still has different plants — more weeds from Europe, less native huckleberry — than the southern section, which had been used as a woodlot. Witham also meticulously logged bird calls: white-throated sparrows tended to gather in recently harvested areas, while ovenbirds preferred intact canopy. At the riverbank, he picked a tick off his hand. Over 30 years, he had collected 3,000 ticks off trapped mice and other small mammals. In that span, he saw deer ticks, the primary vector of Lyme disease, replace nearly every other tick species. All in all, research in the forest resulted in more than 50 published studies during Witham’s time there.

Johnson said Maine TREE plans to do a complete inventory again this year. Going forward, the organization would like to get a handle on what climate change will mean for Maine’s forest economy. Johnson also wants to explore the impacts of selective cuts and controlled burns on the regrowth of salable timber. The mission marks something of a departure from Witham’s broad, academic approach to studying Holt. Still, Witham says he’s glad the forest is being put to continued use — that “people do value the long-term ecological research that’s taking place here.”

On the walk back, near a waist-high stand of huckleberry in brightly lit understory, he called out to Johnson that he’d spotted a hopeful sign. It was something they hadn’t seen elsewhere: a patch of oak seedlings. More trees for the future.