Stonehouse Farm, Bath

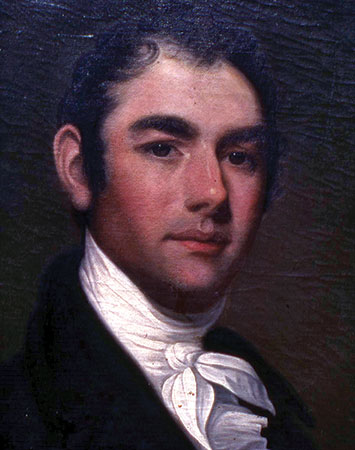

Though we don’t typically turn My Favorite Place over to figures from history, we’ll make a bicentennial exception for William King, the closest thing Maine has to a George Washington figure. Before he became Maine’s first governor, in 1820, King was a leader of Maine’s separatist movement. He’d grown up in Scarborough, in a prosperous family that fell on hard times before they could send him to college. So while his older brother, Rufus, graduated Harvard, then went off to represent Massachusetts in the Confederation Congress and at the U.S. Constitutional Convention, William took a less glamorous path, moving to Topsham in the early 1790s to run a sawmill.

He made money, though, and around the turn of the 19th century, he moved to Bath and started investing in banks, shipbuilding, and overseas trade. He made a bunch more money, and soon, wags around the District of Maine were calling him “the sultan of Bath.” King was elected to serve in the Massachusetts legislature, and he grew frustrated with the Commonwealth’s failure to protect Maine’s interests during the War of 1812, in which he served as a major general in the state militia. After the war, he led a junta of Maine politicians, lawyers, and writers agitating for independence, pushing the 1819 referendum that (after a few failed attempts) found Mainers overwhelmingly favoring separation.

Tall and stentorian and a bit on the haughty side, King had a tendency to take charge of a room, and he headed up Maine’s Constitutional Convention. After the U.S. Congress admitted Maine in March of 1820 (on the condition that slave-holding Missouri also be admitted, to preserve the balance of slave and free states), Maine citizens elected him governor. He served just over a year before President James Monroe offered him a diplomatic post in Washington.

Throughout King’s rise, he and his wife, Ann, often retreated to their summer home of Stonehouse Farm, 100 idyllic acres of fields, pastures, and fruit orchards on Whiskeag Hill in Bath. At the heart of the property was a dramatic Gothic Revival lodge, built of granite blocks, today known as the William King House, a private home listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A biographer described it in 1916 as “a quaint old stone house, with tall cathedral windows and with the gay gardens and spreading trees of olden time . . . just as it was when Governor King and his lady so royally welcomed guests.” Topped with a cupola from which King could admire his merchant ships on the Kennebec, it was a stately retreat fit for a governor — or a sultan.