Introduction by Will Grunewald

From our December 2024 issue

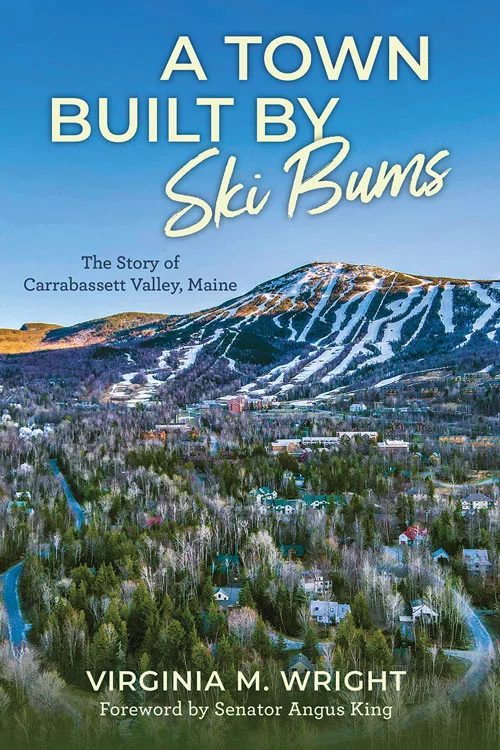

To the untrained eye, the town of Carrabassett Valley might not look like much of a town at all, author Virginia M. Wright points out at the start of A Town Built by Ski Bums: The Story of Carrabassett Valley, Maine. There’s Sugarloaf, of course, the state’s tallest ski mountain and the reason that the local population of fewer than 700 swells to some 10,000 on prime snowy weekends. But beyond the huddle of shops and restaurants built up around the mountain’s base lodge over the past half century or so, there’s not a whole lot else to see for someone just passing through. “On a few occasions, visiting feature writers, confounded in their search for a downtown with white church, historic homes, and brick storefronts, have concluded that Carrabassett Valley isn’t a real town and it’s just another name for Sugarloaf resort,” Wright notes. “They’re wrong.”

What Carrabassett Valley really is, Wright concluded after years of research and writing commissioned by the Carrabassett Valley History Committee, is entirely its own kind of town, conjured into existence relatively recently, in a manner unlike any other municipality in Maine.

Despite a meager population base, the town itself — not Sugarloaf resort — owns a world-class golf course laid out by famed designer Robert Trent Jones Jr., an extensive network of trails for Nordic skiing and mountain biking, a small airport, a fitness center with an indoor climbing wall and a skate park, a large public library and community center, and a public swimming pool. And despite managing an outsize roster of properties, the local tax rate is incredibly low, thanks to creative approaches to local governance. For instance, the police force is a public-private partnership with Sugarloaf — the police chief, a public employee, manages a team of officers whose salaries are paid by the resort. It’s possibly the only such arrangement in the country. “Town leaders set policies and accomplished projects in unconventional ways,” Wright writes, “because they were well educated, skilled in diverse occupations, and young and unfamiliar with notions of How Things Should Be Done.”

To tell the full story of how Carrabassett Valley came to be, though, Wright digs back further — all the way to the geologic forces that would shape the valley and surrounding mountains. She goes on to discuss the arrival of Native peoples, colonial impacts, and 19th- and 20th-century timber harvesting in what were then the unorganized territories of Crockertown and Jerusalem. Then, she arrives at the nation’s postwar ski boom, which drew to Sugarloaf the ski bums who would, in time, bridle at the influence of the state’s Land Use Planning Commission (then called the Land Use Regulation Commission), the body that oversees unorganized territories. In this excerpted chapter, “Whiskey Valley,” Wright recreates the rollicking après-ski scene that helped unite what would become Carrabassett Valley’s motley crew of founding mothers and fathers.

On New Year’s Eve in 1968, a 20-year-old accountant named Larry Warren left his office in Boston and drove north, destination Sugarloaf/USA, in Crockertown, Maine. A novice skier, he’d studied ski-area maps before settling on Sugarloaf for his first big-mountain escapade. It had what he was looking for: adrenaline-pumping slopes and, nearby in Jerusalem, one of New England’s liveliest ski-town nightspots, a converted barn called the Red Stallion Inn, where he’d booked a room for the week.

When Warren pulled into the Stallion’s snow-packed parking lot four hours later, it was dark, snow was falling, and temps were in the low 20s, but the barn’s windows were wide open, blaring rock music and expelling cigarette smoke. (Open windows, Warren would learn, were the Stallion’s ventilation system, no matter the season.) Just inside the entrance, Warren told the young guy collecting cover charges that he had a room reservation. “Let me get my brother,” the kid said, and he disappeared into the crowded bar.

A few minutes later, another young man appeared. Shifting the toothpick balanced on his lip, he introduced himself as Ed Rogers and invited Warren into his office. “We’re looking forward to your stay here this week,” he said, “but tonight we’ve got a little problem.”

“Oh, yeah?” Warren said warily.

“We’re overbooked. We don’t have a room for you.” But if Warren didn’t mind, Rogers quickly continued, he could sleep in the women’s bunk room, free of charge.

Warren didn’t mind (he was 20, remember). Rogers then escorted him into the dining room and introduced him to the bartenders and the waitstaff, who were told to give him all the free drinks he wanted and a free steak dinner too, and to the hat-haired, jeans-clad regulars drinking beer and throwing quarters across the back bar into the tip bucket — a black bedpan affixed to the wall. The room vibrated to the thumping music; the small sunken dance floor bounced under gyrating feet. “I thought, ‘This place is nuts!’” Warren, the visionary behind several Carrabassett-area institutions including the Sugarloaf Golf Club and Maine Huts and Trails, recalled many years later. “Everybody was happy and loose, open and friendly. I couldn’t imagine going into a hotel and being treated like that. I loved it.”

Sugarloafers of the sixties and early seventies had a nickname for their woodsy retreat: Whiskey Valley. It encapsulated their enthusiasm for their favorite activities by day (“we ski”) and night (no explanation needed), as well as the buoyant anarchy that prevailed in their settlement. As unorganized townships, Jerusalem and Crockertown were essentially lawless. There were no select boards to impose ordinances, no codes officers to issue citations, and no local cops to patrol Route 27. Residents remember interacting with two state troopers — one who cruised the beat for many years and the young academy grad who briefly replaced him — before State Trooper Ron Moody arrived. Moody had an avuncular enforcement style, according to former Red Stallion waitress Meg Rogers, who remembered him striding through the bar and pointing to the most inebriated revelers: “You’re not driving . . . you’re not driving . . . you’re not driving.” Moody, who became Carrabassett Valley’s first police chief, in 1988, and created its blended town-resort police force, later told the Daily Bulldog that he’d been more of a guardian than a disciplinarian. “Arrest isn’t my philosophy,” he said. He traced his approach to the advice given him when he was a 19-year-old rookie in Ogunquit: “We’re in the resort business,” the chief had told him on his first day. “We’re here to take care of people.”

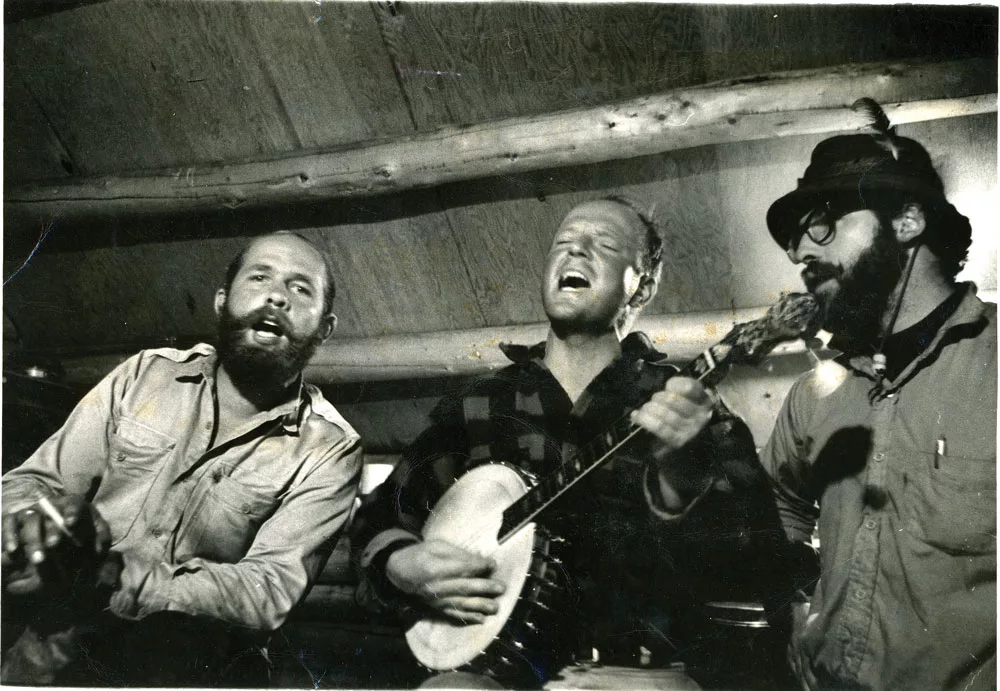

Despite all the construction that had taken place over the 20 years since the Bigelow Boys cut their first trail on Sugarloaf Mountain, Carrabassett Valley still felt like the middle of nowhere, particularly to city dwellers like New York Daily News reporter Jerry Kenney. When he visited in 1969, Kenney felt he’d stumbled upon a ski-country Brigadoon with mysterious magnetic charms. “Skiers have been known to come here for a season finale and never be heard from again by the outside world,” he said. “The lure of Sugarloaf alone is powerful enough, but coupled with life in the valley, its inhabitants and their mores, it’s almost overpowering. . . . After dark, that’s when the lure of Carrabassett Valley really gets to the visitor. Following dinner, there never was much to do except listen to the local people talk fishing or hunting. Or if one could find where Jud Strunk was plinking his banjo and reciting Carrabassett verse, they’d flock around.”

The après-ski scene may have been small, but the young clientele’s enthusiasm for partying was huge and unabashed — the inspiration, in fact, behind the name of The Bag restaurant and bar (everyone was “half in the bag” — get it?). The Bag’s proprietors, Billy Jones and Icky Webber, even gave their friends keys to the back door so they could grab beers on Sundays when Maine’s Blue Laws prohibited stores from selling alcohol.

Jones, who’d grown up in Eustis and had been working at or around Sugarloaf since he was a 15-year-old flipping burgers in the base lodge, played bass fiddle in Jud Strunk’s popular folk ensemble, the Sugarloafers, aka the Carrabassett Grange Hall Talent Contest–Winning Band. That made him an especially valuable member of the Bad Actors comedy troupe. The group’s instigator was Philip “Brud” Folger, a University of Maine ski-team coach, who said he and his friends would come off the mountain after a day of skiing and say to each other, “What are we gonna do?” followed by “I don’t know,” followed by drinking at one of the local bars. One night in 1967, over beers at the Capricorn Lodge, Folger told his friends about his junior year abroad in Austria and how everyone would gather in a hotel bar to watch the ski instructors put on shows with yodeling, guitar playing, singing, and dancing. Inspired, the party retreated to Bigelow Station, the Folger family’s camp, and concocted several skits to perform as an opening act for the Sugarloafers, thus guaranteeing they’d have an audience. Exactly which of the newly founded Bad Actors was there that first night varies with the storyteller, but the cast ultimately came to include Bud Folger, Icky Webber, Parker Hall, Dave Hutchinson, Ted Jones, Carl “Dutch” Demshar, Billy Jones, Jud Strunk,

and Al Scheeren.

The Bad Actors were a top après-ski attraction for six or seven years, most often performing at the Capricorn Lodge, which had the best space for their antics, not to mention a bartender who rewarded them with a better-quality bourbon than what they received at other venues. Exuberantly unrefined, the Bad Actors had no ambitions beyond the valley; they were content to be silly in front of an audience of friends. Their signature routine featured four barflies puzzling over a minute object that they passed amongst themselves fingertip to fingertip, until one of them revealed he’d found it in his nose. “We started every performance, if you want to call it that, with bourbon and a couple cases of beer,” said Demshar, a former Brunswick Naval Air Station pilot who settled in the valley in 1968 and eventually became one of the area’s most prolific building contractors. “Most of the time, I was the light man. Each person who was participating in a skit would go on stage, and when he was ready, I’d turn on the light. They’d do their monologue or joke or whatever it was, and then I’d turn the light off. It was very quick. The average show had about 25 jokes, some of them relatively risqué, most not.”

By far the rowdiest bar in the valley, the Red Stallion served its first cocktail at 12:01 a.m. on January 1, 1962, according to a written remembrance by Dave Rollins, who converted the former Dead River horse barn into a restaurant and hostelry with his business partner, Wes Sanborn. Staff members Florence Hall and Laura Dunham designed the renovation: Just inside the front door was a small lobby with an office to the left and a bunk room to the right (some years later, the bunk room was refashioned into “the little bar”). A staircase led to pine-paneled guest rooms in the former hayloft. Straight ahead was the super-rustic dining room, with booths around the edges and a bar against the back wall. The dance area sat a few inches below the tile-red softwood floor; local legend holds its notorious springiness was due to its resting on a bed of horse manure, but more likely the dance floor bounced because it was built on beams instead of a solid foundation, according to Ed Rogers. Rogers didn’t deny, however, that the dining room sometimes had an eau de barnyard, particularly during heavy rain.

On stage that New Year’s morning in ’62 was Jud Strunk, Billy Jones, and pianist Ed Krause. Strunk, then 26 and a recent transplant to the area from upstate New York, went on to form what was for a time the Stallion’s de facto house band with trombonist Bob Marden, clarinetist Dick Dubord, and trumpeter Fred Petra. “Often impromptu, Dick Dubord and Jud Strunk brought the house down with their stand-up comedy routines,” Rollins writes. “The Stallion was a wild and woolly place, but usually under control because Florence Hall and Laura Dunham commanded great respect from the regulars — a combination of local Jud Strunk fans, Sugarloaf staff, and skiers.”

[CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE]

Clockwise from top left: Bartender Peter Roy, Austrian ski racer Karl Schranz, and Red Stallion owners Ed and Wendy Rogers in 1971; Sugarloaf trailblazer Amos Winter in 1962; before skiers came to the valley, boardinghouses catered to sportsmen; Sugarloaf Motel ad; Amos and Alice Winter selling tickets in 1956; Sugarloaf employees in 1955; the Red Stallion in the 1960s — the old barn made way for housing development a couple of decades ago.

It became wilder and woollier when the Rogers family took over 1966. The business was in foreclosure after its second owner, John Love, had been unable to make the mortgage payments, and Ed convinced his father to take out a bank loan to acquire it. Ed was determined to turn the Stallion into a nightspot on par with Killington’s Wobbly Barn and Sugarbush’s Blue Tooth. Dinner hour at the Stallion was wholesome, especially Thursdays when two-for-one specials were a big draw, but as the evening progressed, the families cleared out and the ski bums moved in, transforming the dining room into a nightclub that had a New England–wide reputation for hosting great bands. “I kept trying to push the limit of making the Red Stallion the place to go — getting bands and the whole works,” Rogers said. “And it worked. We had monster crowds right from the start. I always was jealous if we didn’t have the most people staying at our hotel and the most people at my bar at night.” Overbooking rooms was so common that staff joked that when guests arrived, they’d find Ed so he could introduce them to the couple they’d be sleeping with.

Rogers hired a Pittsfield band, the Missing Links, to play most weekends, and its trumpeter and pianist, Leon Southard, sometimes performed through the week. The most popular band, at least among the Stallion’s female patrons, was Molly McGregor, according to Meg Rogers. The long-haired lead singer, Hank Castonguay, started each set writhing under a blanket on the floor of the darkened stage. When the music kicked up and the lights flashed on, he’d leap to his feet, wearing less clothing than he’d had during the previous set. By evening’s end, he’d be clad in only a leather jockstrap.

The Stallion’s management team included Ed’s wife, Wendy, and his brothers, Frank and Bob (it was Bob who was collecting covers on the night of Larry Warren’s first visit). Each of the male staff members was known to regulars by his nickname — Captain America (Peter Roy), the Rooster (John Corcoran), the General (Terry Snow), White Trash (Mike Sheridan), and Groovy Garbage (Jim Nickerson), to name a few. The crew continually cooked up causes to party around, like the Miss Ayotte Country Store Pageant and, during one snow-poor winter, Beach Week, when a load of sand was piled in the dining room.

The Red Stallion’s reputation for barely contained chaos belied its role as an incubator for on-mountain and valley-wide projects. It’s where Ed Rogers, David Rolfe, and Harry Baxter dreamed up Sugarloaf competitions like Horror Week, during which the Stallion staff proudly skied in white coveralls emblazoned with the words Red Stallion Horror Team. Rogers launched the Irregular newspaper in 1967 out of the Red Stallion dining room, with Liz Hall as its first editor and, a year or two later, Rolfe as its first full-time publisher. Rogers also led the Sugarloaf Area Association as it created a central phone number for booking lodging and organized events like White White World, a weeklong costume party across several venues that culminated with the crowning of a Sugarloaf king and queen. His most significant accomplishment was the founding of the North America Pro Ski Tour, which evolved into the World Pro Ski Tour.

The morning after his stay in the women’s bunk room, Larry Warren took a lesson with Sugarloaf ski-school instructor Dick Allison. “His approach to teaching was to take me to the top of the mountain and go down the Narrow Gauge and over the head wall, then just stay on the number three T-bar and the hardest part of the mountain all day long,” Warren said. “I crashed and burned and tumbled. By the end of the day, I made one run over the head wall without falling. He said, ‘There! If you can do that, you can do anything!’” Warren went back to the Stallion for more steaks and beer and dancing. That was his routine for the rest of the week.

After that, he spent weekend after weekend at the Stallion. He became friends with the Rogerses, the bartenders, and the regulars, including businesspeople from around Maine who had camps in the valley. In January 1970, one of them, Portland-based accountant (and future Carrabassett Valley selectman) Alden Macdonald, offered him a job working with one of his biggest clients — Sugarloaf. Warren accepted, but within a few months, Sugarloaf general manager Charlie Skinner hired him, with Macdonald’s blessing, to replace Ted Jones as controller (Jones left to start a woodworking business).

After work, Warren often went to the Red Stallion to drink beer and play cribbage. “It was like the local gossip center, like going to the hairdresser,” he said. One afternoon in 1971, he and his friends — Ed Rogers, David Rolfe, Ted Jones, and the soon-to-be founders of Tufulio’s Restaurant, Joe Williamson and Larry Sullivan — got into an animated conversation about [Dead River timber company executive] Chris Hutchins’s crazy idea for getting out from under Land Use Regulation Commission’s jurisdiction. Warren remembered their excitement building as they considered the benefits of creating their own town: “We’d keep our tax money instead of sending it to the state . . . the world will be our oyster . . . we can do some wild and crazy things . . . hey, this is going to be fun!”

Ready to read more? Order an author-signed copy of A Town Built by Ski Bums online here.