By Willy Blackmore

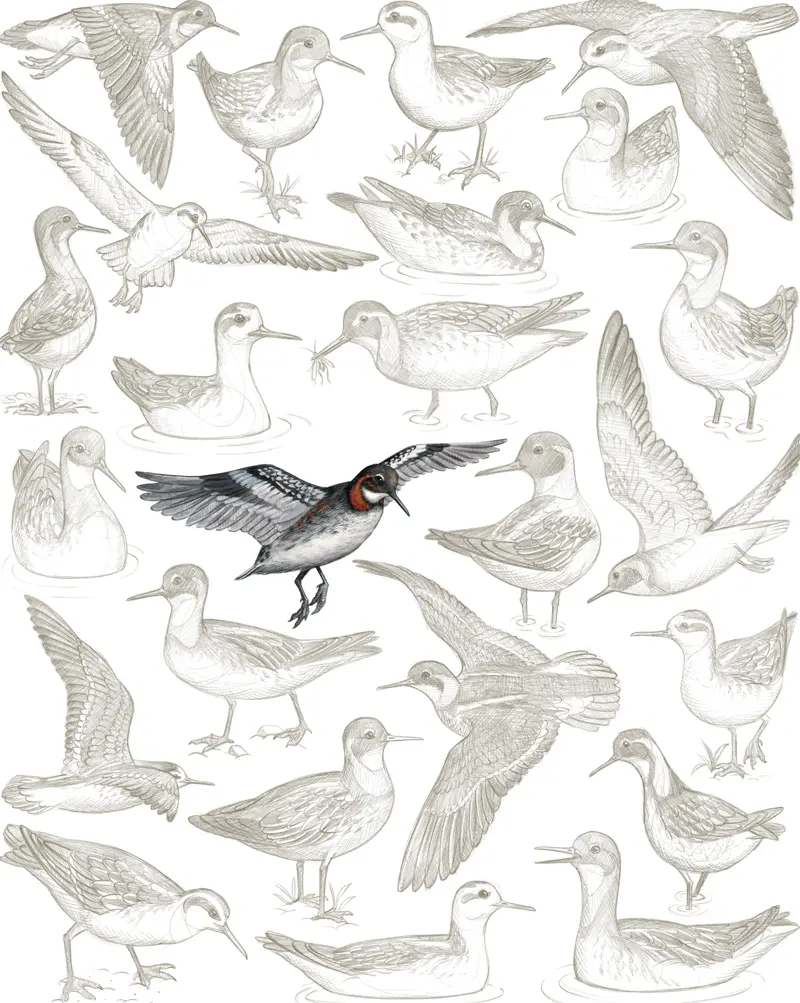

Illustrations by Jada Fitch

From our October 2022 issue

Charles Duncan never exactly planned on coming to Maine. During the summer of 1981, he was off from his job teaching chemistry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and he was renovating his house — a big project that became overwhelming when Duncan found out his contractor was cheating him. “I couldn’t sleep,” he remembered. “I said, ‘I gotta get out of here — I want to go on a bird-watching trip, and I don’t even care where.’” He found an August tour through down east Maine and Canada’s Maritime provinces and booked it immediately.

A few weeks later, he was out on a boat in Passamaquoddy Bay, heading from Lubec toward New Brunswick’s Deer Island. Remodeling woes out of mind, Duncan marveled at the vast tidal flats and the many forested islands dotting the water. “I was used to going to the beach and there would be this big ocean that would continue on to Europe,” he says. And it wasn’t just the tides and wending coastline that impressed him: bobbing around the waves were masses of tiny seabirds — so many that Duncan sometimes thought he was seeing nothing but rippling water until, suddenly, a flock would peel off the surface like a cloud of smoke. “There were flocks of a thousand, two thousand at a time,” Duncan remembers. “I was incapable of estimating — I had never seen numbers like that before.”

In those days, as many as two and a half million of the birds, called red-necked phalaropes, would funnel through a small slice of the bay, around Canada’s Campobello and Deer islands, in the late summer, gorging on tiny plankton, before continuing their journey from their Arctic nesting grounds to the open waters of the Pacific, off the coasts of Ecuador, Peru, and Chile. It was a glimpse of a mass migration on a scale that even career birders and ornithologists say was without comparison. “I remember the most frequently heard question was how many are there?” says Davis Finch, the since-retired birding guide who led Duncan’s trip that summer, plus countless others in Maine and across North and South America. “That was the question that dogged all of us, and there was no answer, really.” It was, Finch said, an “intellectually dizzying” number of birds.

But on a hot day this August, as the growls and fuzzed-out guitars of a local metal band rang out from a park overlooking the Lubec Narrows, I spotted exactly as many red-necked phalaropes feeding on the rush of the rising tide as I expected: none at all. It was the same looking out toward the fog bank hanging over Canada’s Grand Manan island from beneath Lubec’s candy-cane–striped West Quoddy Head Light, the same in the water that courses between the pine-peaked islands dotting the bay between Lubec and Eastport, to the north. That’s because the massive flocks of phalaropes, documented in Passamaquoddy Bay since at least the 1830s, all but disappeared more than 30 years ago. What the late Peter Vickery, author of the definitive Birds of Maine, called “one of the most remarkable avian events” in eastern North America has been reduced to just a few stray phalaropes showing up here or there during the southern-migration months, as if they were wayward birds flown off course. To this day, no one is sure what happened to those millions of birds.

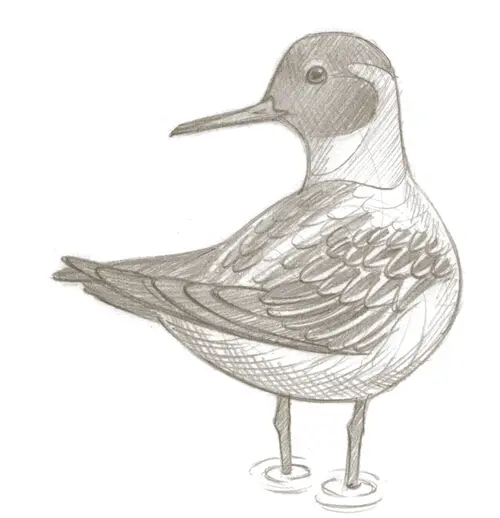

The red-necked phalarope is an odd little bird. Its name comes from its breeding plumage, which features a rust-red patch that wraps around the throat and up to the ears, like a flipped-up collar, of the larger and more brightly colored females (male birds have the patch too but less vibrant). A phalarope spotted in Maine, however, would likely have already molted, adopting the more drab gray-and-white coloring the birds wear during migration and wintering. With their dainty oval shape and slender beaks, phalaropes draw comparisons to other shorebirds, like sanderlings and piping plovers, but you’ll never spot one wading through the surf and pecking at the sand. Rather, phalaropes spend nearly all of their lives at sea, bobbing high on the open water thanks to their breast and belly feathers, which are so dense that they trap air and act like a buoy.

Phalaropes are an anomaly on the open ocean because they cannot dive. Instead, they excel at finding ways to bring their preferred prey, a type of plankton called Calanus finmarchicus, up from the deep to where their slender beaks can reach them. Plenty of other animals also feed on these particular plankton; the Gulf of Maine is at the southern end of the species’ range, and all throughout the North Atlantic and up into the North Sea, the drifting copepods are among the primary building blocks of aquatic life. Endangered North Atlantic right whales, cod, haddock, and herring are all heavily reliant on C. finmarchicus at various life stages.

Individual phalaropes swim in tight circles when feeding, drawing up plankton in the tiny whirlpools they trace in the water. Similar swirling currents, but on a larger scale, are what attracted the birds to the Quoddy region — shorthand for the border-straddling southernmost reaches of Passamaquoddy Bay, itself an inlet of the massive Bay of Fundy, and the islands and peninsulas of Maine and New Brunswick that interrupt it. Those waters are home to Old Sow, the Western Hemisphere’s largest whirlpool, along with some of the world’s most dramatic tidal variations. All that water rushing in with the tide — transforming areas around Lubec, over the course of six hours, from muddy clam flats to seas 28 feet deep — creates a significant upwelling. And the deep seawater drawn to the surface is rich with C. finmarchicus. At least, it was back when the phalaropes still came around.

Much as his first trip brought him to Maine arbitrarily, Duncan found himself living here seemingly by chance. After the birding tour, he was back in Alabama for the fall semester when he came across a job posting for a faculty position at the University of Maine at Machias. He applied, got hired, and quickly found himself down east again, this time to stay.

At the same time, his fondness for birding was deepening into an obsession. “I had started watching birds just like anyone else, as a hobby — and then that hobby got pretty badly out of control,” he says. The move to Machias made it even easier to indulge his passion: not only was he a short drive from the destination birding area of Passamaquoddy Bay, he was also introduced to Butch Huntley, captain of the M.V. Seafarer, a 48-foot whale-watching charter that docked in Lubec. “I had summers off at my academic job at the time, and Butch was kind enough to let me hitchhike for free with him,” says Duncan, now 73 and living in Portland. Their friendship enabled Duncan to go birding on the water about as often as he wanted.

Those first summers out on the Seafarer, Duncan and Huntley weren’t looking for phalaropes — during the migration season, from July through September, you’d have had to try very hard not to see them. But Duncan always takes notes while birding, including estimated totals for every species he sees in a day, whether herring gulls, ospreys, or red-necked phalaropes. “One of the early years, maybe 1984 or so, my highest total for one day was 20,000,” he says. The next year, however, it was more like 2,000. He and Huntley wondered how they’d managed to miss the birds: maybe they hit the tide wrong, or the flocks were in a different part of the bay? But come the next summer, Duncan’s top one-day total was just 200 red-necked phalaropes. Clearly, it wasn’t a question of missing the birds. The birds were gone.

In 1989, Duncan and Huntley saw no more than 20 phalaropes in a day. “And we sort of looked at each other and said, ‘Do you think we should tell somebody?’” Duncan remembers. (Huntley died in 2012.) And then, another thought: “Here’s this guy who’s a whale-watch captain and me, a professor of chemistry — who is going to listen to us?”

But Duncan did spread word of the phalaropes’ disappearance, slowly, writing bulletins in birding newsletters and articles in ornithological journals, and updates trickled back from elsewhere along the phalaropes’ hemisphere-spanning migration route. Phalaropes’ Arctic nesting grounds aren’t like those of some other shorebirds that nest further south, like plovers’, which are tightly packed among dunes. Female phalaropes instead seem to prefer solitude for nesting sites, which there’s plenty of across the open tundra of the eastern Canadian Arctic, Greenland, and Iceland. (Red-necked phalaropes also nest in western Canada and Alaska, but they follow a western migratory route, and a separate European population has altogether different wintering areas.) As far as any of Duncan’s correspondents could say, nothing looked out of sorts up in the Arctic, and phalaropes were being seen in their usual numbers along western migratory routes. There was no evidence that the millions of red-necked phalaropes from Passamaquoddy Bay had died — but they were unquestionably missing.

“Anyone who has had a car stolen will recognize the desperate feeling,” begins Duncan’s 1989 paper on the disappearance (pdf), first published in a journal called the Bird Observer. “You know you left it right here, RIGHT HERE, but it’s certainly not here now.” Passamaquoddy Bay, Duncan wrote, “looks normal to most of the summer tourists, but to those who have seen it when the birds were here, it is apparent that something is terribly wrong.”

The paper, later republished by the American Birding Association’s journal, laid out what might have happened to the birds. Their population crash could have been caused by a collapse of the local C. finmarchicus population, Duncan wrote. Or maybe by some disruption elsewhere in their vast migratory habitat. Or there may have been no population crash, the birds having simply moved to some other area in the Bay of Fundy — or the broader Gulf of Maine — where humans weren’t around to spot them.

In the years since, studies have shed more light on potential causes for the disappearance: One, from 2002, found that the amount of C. finmarchicus in surface waters around Lubec has indeed declined, by a factor of 10, since the early 1980s. Another, from 2015, suggested that a harsh El Niño winter in 1982–83 put a dent in the breeding population while in the Pacific — although its authors acknowledge the decline doesn’t match the scale of the disappearance in the Quoddy region, “so that a local explanation (specific to the Bay of Fundy) is probably required as well.” While the body of research on red-necked phalaropes isn’t vast, a small but obsessive group of ornithologists have continued to try and solve the mystery.

“That’s what gripped me: How could this possibly be? Where did they go?” says Robin Hunnewell, who performed Bay of Fundy population surveys of red-necked phalaropes and closely related red phalaropes between 2008 and 2010, while a PhD candidate at the University of New Brunswick. Her count, conducted from an airplane, looked at a wider area than where Duncan and Huntley were boating in the 1980s, encompassing the waters around Canada’s Grand Manan and Brier islands, at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy. Red-necked phalaropes were found in both spots back in the ’80s, but in far smaller numbers than in the Quoddy region, and their numbers were dwarfed by large flocks of red phalaropes. What Hunnewell and her colleagues found was unexpected: big flocks of both species — around 290,000 total birds in 2010 — around half of them red-necked phalaropes. That survey (and another, conducted by the Canadian Wildlife Service a few years later) suggested that some of the lost birds had found new staging areas nearby — but still only a fraction of the historical multitudes, leaving the mystery of the missing phalaropes unsolved.

“There is an aura of mystique around this bird because of this,” says Hunnewell, more recently an educator for Mass Audubon. “I was completely beguiled by it — like, I have got to figure this out.” But among those who have tried, she says, “everyone comes away sort of broken.”

If a handful of people care deeply about what happened to the phalaropes, the great majority have never even heard of them. Even around the Quoddy region, locals told me, they are little remembered or mourned. Eastport artist Richard Klyver, who fished out of Eastport in the ’70s and ’80s, remembers seeing phalaropes by the thousands, but he says most other fishermen didn’t seem to take notice. Years later, Klyver recalls, he led a mural project for local schoolkids, with Passamaquoddy Bay marine life as its theme. “One of the things I had them paint was these flocks of phalaropes — hundreds of little birds,” he says. “These kids had never heard of phalaropes.”

Meredith Huntley, whose late father hosted Duncan on the Seafarer, spent plenty of time on the water with her dad. She remembers marveling at the strange migratory birds — “flocks of them as far as the eye could see, like a brown carpet going on for miles” — and at their murmurations, the way they would all rise up off the water together and “somehow knew to turn at the same time.” More recently, she asked another whale-watching captain, a peer of her dad’s who spent nearly 60 years on the bay, what he recalled of the great rafts of phalaropes. His response, she says: “Nope, don’t remember that.”

“The analogy to the tree falling in the forest probably isn’t off by much for the little phalarope,” says Steve Kress, former executive director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program, which famously brought the Atlantic puffin back from the brink of extirpation in the 1970s, reestablishing a colony on Muscongus Bay’s Eastern Egg Rock. “But when a species disappears so dramatically, I think the message is that something has changed, and that’s not just affecting the phalaropes, that’s affecting other things too.”

There’s no question that the Gulf of Maine, which is warming more quickly than any other stretch of ocean in the world, is today changing in dramatic ways. C. finmarchicus is in what biologists call a polar retreat, the southern edge of its range receding away from the gulf. Another of its predators, North Atlantic right whales, down to just 450 individuals worldwide, are shifting their range northward too, moving away from their historic grounds in the Bay of Fundy and instead showing up in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (with more whales dying in the process, due to boat strikes). Meanwhile, the collapse of Atlantic cod populations, which cratered in the early ’90s after decades of overfishing, continues to have ripple effects across the ecosystem. So does the abundance of newly successful species, whether introduced, like green crabs, or migrant, like longfin squid.

We don’t know whether or how the phalaropes’ disappearance is connected to the many subsequent disruptions to Gulf of Maine ecology — in part because so much remains unknown about the species. Advancements in transmitter technology could help shed light on where they went. Today’s trackers are light enough to be carried by monarch butterflies, and affixing them to phalaropes could reveal plenty about their little-understood migration routes. Maybe, as some have suggested, there’s another upwelling out there, far from the shore, where the birds still gather in flocks so thick that they look like smoke when taking flight.

But Duncan, who eventually left academia to work in conservation (first at The Nature Conservancy, then with the Manomet Shorebird Recovery Program, before retiring in 2013), admits that knowing the flight patterns of today’s phalaropes still wouldn’t bring them back to the Quoddy region. “The conservationist in me would say, Charles, even if I gave you that information, what would you do with it? How would you change the conservation status of these birds if you knew that?” For the red-necked phalaropes, there is no equivalent intervention to the reintroduction of puffins to Eastern Egg Rock. As Duncan put it, “You can’t go out in a boat and sprinkle plankton.” Puffins may make better plush toys than phalaropes, but phalaropes — lost quietly and irreversibly and barely even missed — might be the better poster species for an increasingly tumultuous era in the Gulf of Maine.

For Kress, the uncertainty and ambivalence surrounding the phalaropes’ disappearance from Maine waters don’t diminish the loss. “It’s like a great work of art: when it’s gone, it won’t ever be restored,” he says. “Every animal is like a treasure, and when we lose it, when we lose the great mass of its numbers, we all lose something that’s important. And that’s what the phalarope is — it’s a spectacle that we’ve lost forever.”

A few years ago, a friend of Duncan’s, who works for the Canadian Wildlife Service in the Maritimes, sent him some thrilling photos: tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of red-necked phalaropes, amassed off Nova Scotia’s Brier Island, at the southeastern edge of the Bay of Fundy, some 50 miles from Lubec. It’s an area that Hunnewell had surveyed in the late 2000s and where, Duncan says, frequent whale-watch tours have never prompted reports of huge red-necked phalarope flocks. It was the first time since the early ’80s, out on the M.V. Seafarer, that he’d seen evidence of anything close to that many phalaropes in one place at one time.

“One could argue, gee, maybe they just moved over there — maybe the plankton is better over there, and they moved over there as opposed to population collapse,” Duncan says, still turning over the same questions he first raised some 35 years ago. “But that’s just a hypothesis.”

While the mystery remains to be solved, seeing that many phalaropes still made Duncan want to hop in the car and head for Nova Scotia. Maybe he could somehow get out on the water? “I would love to see those kinds of numbers again,” he says. “Seeing any one phalarope is a kick for me. Seeing those kinds of numbers would be like, whoa, look at this!”