By David L. Graham

Photos by Glenn Richmond

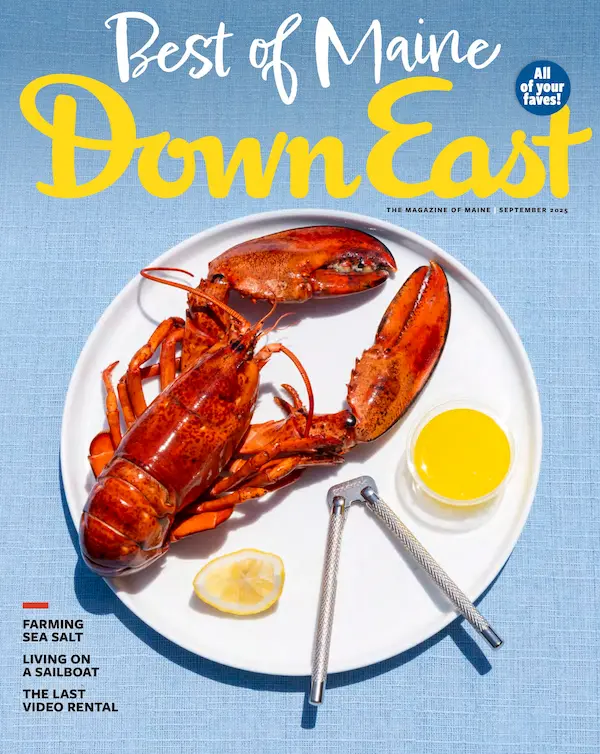

From our November 1970 issue

Suppose you were a farmer and found a porcupine in one of your best apple trees. Would you shoot the beast, or club it to death? I was with Scott Nearing on his Harborside farm when this happened to him. Instead of resorting to violence, Nearing exorcised the pest by tapping it gently with a stick and saying, “Go away and don’t come back.”

Extreme as some of Nearing’s views are — for instance, he believes that our competitive, acquisitive society is on the march to self-destruction — in nothing is he more extreme than in his non-violence. He does not kill either for sport, for food, or to rid his garden of pests. The nearest he comes to using insecticides is to apply a repellent consisting of a finely sifted mixture of earth, lime, and tobacco dust. “The less I interfere with nature,” Nearing told me, “the better citizen I am.”

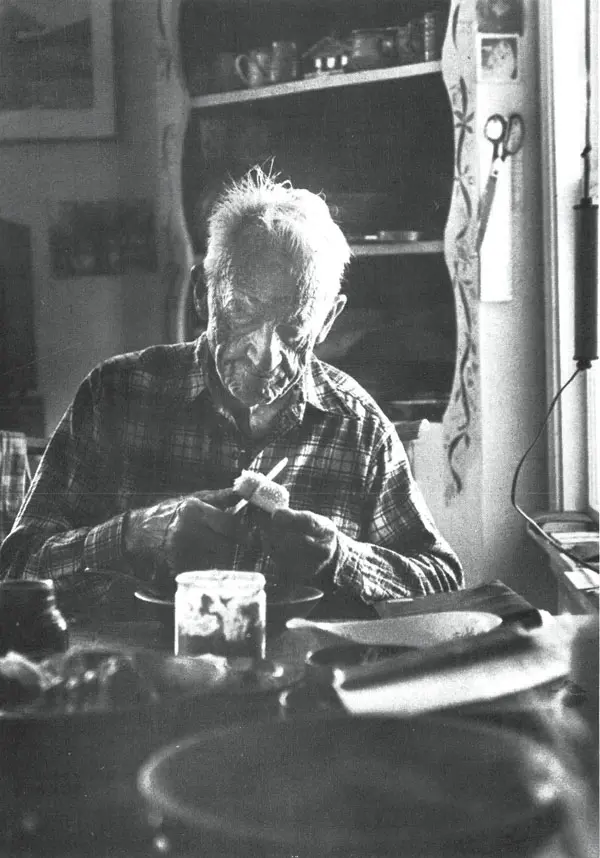

Writer, lecturer, organic gardener, and last of the Old Left, Nearing at 87 is still going strong on an intake that excludes not only hard liquor, but also tea, coffee, and soda pop, as well as meat, fish, and pastries. Scott and his wife, Helen, consume honey and peanut butter by the bucketful; and Helen, as though admitting a weakness for pot, confesses a craving for ice cream.

Rising at about 5 a.m., Nearing remains at his desk until it is light enough to work outside. All his intellectual labors, his gardening, and care of the farm are meticulously prepared for, usually a year in advance. “Our card index for activities has a place for ‘jobs to be done,’ for ‘construction planned,’ and for ‘finished projects.’ Each project has its cost cards with records of materials used and money outlay for specific purposes. Separate loose-leaf books for gardening and maple sugaring contain the plans, current activity reports, and records for previous years.”

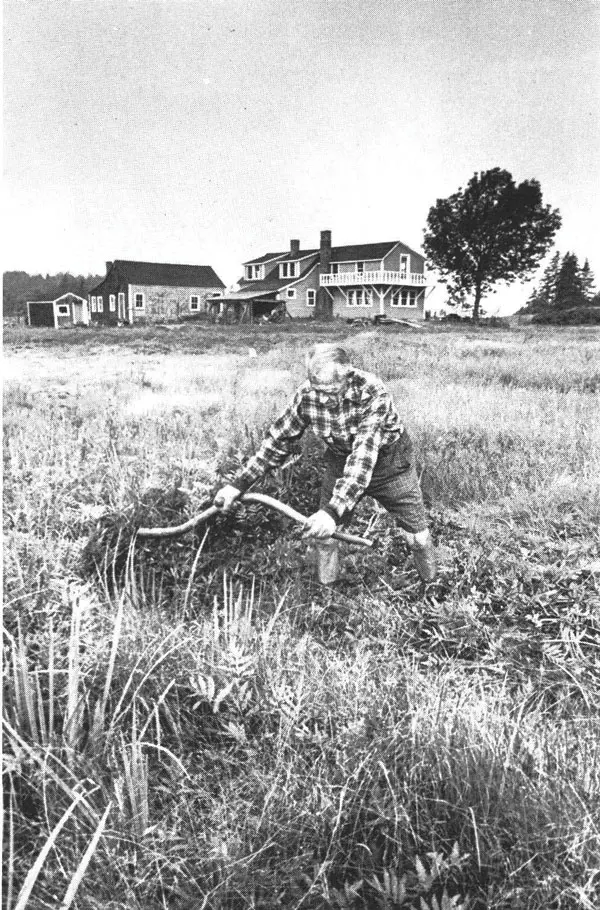

On a breakfast of herbal tea, Nearing goes about his manual labors. Herbal tea? “Nothing like it,” Nearing maintains, “to build stone walls on.” In the last 15 years, he and his wife have built about 100 yards of stone walls to protect their garden from the wild creatures that roam at will over this isolated farm. Nearing also cuts all the wood they heat their home with, about eight cords a year, in winter sallying forth on snowshoes to drag the wood back to the house on a toboggan.

And so Nearing passes the day: reading and writing, cultivating his garden, cutting wood, building stone walls and outbuildings, digging a pond by hand. He wouldn’t have a bulldozer on the place. “Doing things by hand is more fun.” A Churchillian nap after lunch is Nearing’s only concession to advancing years.

Nearing considers himself above all a teacher, even though his radical views exploded him out of the University of Pennsylvania and other teaching jobs more than 50 years ago. He lectures wherever he is invited and has written some 50 books, five of them in collaboration with his wife, publishing most of them himself.

Weatherbeaten and wrinkled but unbowed by the years, Nearing has a firm, sinewy figure and a presence that makes one proud to shake his hand. For Nearing has not only written books and lectured to thousands of people in his time, but he has also built several stone houses, raised two sons, traveled over much of the world, and made a garden spot of a remote, run-out farm on the eastern shore of Penobscot Bay.

Anyone who visits the Nearing farm at Harborside, on Cape Rosier, is almost inevitably drawn into some project. Only at mealtimes and seminars do the Nearings sit around talking. On a recent visit, saving my questions for the meal hour, I chivalrously held the wheelbarrow while my octogenarian host pitched it full of compost for his blueberry bushes.

Luncheon consisted of vegetable soup, a mixed salad, homemade bread, johnnycake made of carrots from which the juice had been extracted, and rose-hip jam. The Nearings ate their salad with chopsticks, convinced that metal utensils impair the taste of things. I was mercifully furnished a fork, but managed the soup with a wooden spoon.

Although it was late May, for dessert we had russet apples which, along with various root vegetables, had been stored since the previous autumn in boxes of leaves in the cellar. The Nearings produce about 80 percent of their food, buying only oranges, lemons, raisins, margarine, peanut butter, brown sugar, honey, and little else. I tried a rose-hip drink which my taste buds, calloused by years of addiction to coffee and tea, found rather insipid.

“Why so much manual labor?” I asked, thinking of all the hand-sawed wood, handlaid masonry, and the hand-dug pond. “Well,” Nearing answered, “if I’d just sat here with my feet up, by now I’d have gout or be dead.”

Frugal in habits and frugal of speech — chitchat is not his forte — Nearing is also frugal of dress. It is a matter of principle with him to “keep his personal expenses to the minimum.” There is more than a little of the puritan in Nearing, doubtless one of the factors that drew him to New England. “Satan finds mischief for idle hands,” he noted in The Conscience of a Radical. The advice he gave to his last class at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught for nine years, was in a similar vein: “Boys, get a real job this summer. Don’t go to a summer resort and waste your time hanging around women.”

Yet, for all the austerity of his ideals, Nearing is soft-spoken, mild-mannered, friendly, hospitable. And although he believes that only “a cooperative, socialist world community” can save mankind from self-annihilation, no life has been more intensely individualistic than his. Chided by an admirer for this inconsistency, he smilingly quoted Emerson: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

No party or sect has been able to hold him. In his youth, he broke with organized religion, but he still sees “a magnificently planned, ordered, and expanding universe.” Just as he was forced to resign from the University of Toledo for opposing America’s entry into World War I, so a few years later he was expelled from the Communist Party for opposing the party line. He has admirers by the hundreds all over the country, but even the small, esoteric readership of the Monthly Review, for which he writes a regular column, cannot count on him for conformity. While a lead article was lambasting the “Establishment” for the moon shot, in the back of the magazine Nearing was sturdily hailing it as “a turning point in human history.”

Fed up with civilization, which he calls “cityism,” and seeking the independence and contentment that comes from living close to nature, the Nearings quit New York City in 1932. For $300 down and an $800 mortgage, they bought a played-out farm in the vicinity of Stratton Mountain, Vermont. They had intended to market timber to supply the wherewithal for the things they couldn’t produce themselves. But later, having bought additional acreage containing large stands of maples, they eased themselves into the maple-sugar business and developed it into a profitable sideline. This they did without violating their principle of devoting but four hours a day on the average to “bread labor,” or subsistence farming, while reserving the rest of their day for study, writing, social intercourse, music, and travel. How they attained this good life is described in their two books, The Maple Sugar Book and Living the Good Life.

The good life was their goal, not affluence, which they consider corrupting. Consequently, partly out of distaste for too much financial success and partly from dread of the land boom they saw headed their way, the Nearings sold their Vermont holdings in 1951. Financially, they could have made a killing. Later, the same property changed hands for close to $100,000. All they wanted was $15,000 which, they reckoned, was what they had put into the place in capital and labor. Although their woodlot had appreciated 800 percent, they gave it to the town. It is easy to disagree with Scott Nearing, but impossible to deny that he has been faithful to his principles.

Nearing was approaching 70 when he and Helen began all over again on a remote, abandoned farm in Maine. They welcomed the quiet and seclusion for study, but what especially pleased them about their 140-acre homestead on Cape Rosier was that it overlooked the sea. The land hadn’t been farmed for 28 years, but the house was in good condition and the Nearings brought a ton and a half of their precious organic compost from Vermont. As organic gardeners, the Nearings are purists — no chemicals, no animal manures.

In 1958, when I first saw the Nearings’ garden, it was a miracle of husbandry, with pea vines 10 feet tall and jumbo-size raspberries. Already they had built a stone, solar-heated greenhouse in which throughout the winter they grew lettuce, parsley, cabbage, and other hardy greens. But the stone wall with which they intended to surround the garden was barely started. Today, that five-foot wall is almost finished.

Some years, the Nearings spend all four seasons on the farm. In fact, it was the seasonal changes that brought them to northern New England in the first place. “A year of all summer is as deadening as a year of all winter would be,” they wrote in The Maple Sugar Book, and they theorize that “soft climates probably produce soft people and certainly produce parasitic people.”

Yet Scott Nearing is no recluse. Travel is not merely part of the good life; travel is essential to him as a teacher and expounder of a lifestyle. One day last fall, for example, he dug the remainder of his carrots and stored them in the cellar, drove 150 miles to lecture at Bowdoin College, and the following morning continued on to Boston for more lectures prior to a trip to Israel.

Some winters, Scott and Helen have crisscrossed America by car, teaching and learning. Describing these travels in USA Today with characteristic attention to detail, Scott recorded: “During the 488 winter days we were away from home . . . we traveled over 50,000 miles, through 47 states, and held around 600 meetings and get-togethers, which were attended by some 30,000 people.” In other winters, they have visited Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

So this 87-year-old man, belonging to no party and no sect, goes about the world in person and in his books, condemning violence and preaching the gospel of “the least harm to the least number and the greatest good to the greatest number.” But recognition is overtaking Nearing at last. This summer, ironically enough, the University of Pennsylvania, which fired Nearing in 1915, jumped at the privilege of publishing his autobiography.