On Maine’s Cape Rosier, Scott and Helen Nearing built their own stone houses, grew their own food, and stepped to their own music. Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project’s Thoreau Institute Library.

By Melissa Coleman

From our April 2020 issue

Readers tell similar stories about their first encounters with the book. Many seemed to have found it at health-food stores, and many say they read it in a single sitting. Some were moved to write the authors, expressing their admiration, while others were so inspired that they drove or hitchhiked to Maine, to a plot in Brooksville called Forest Farm, where homesteaders Helen and Scott Nearing welcomed them, fed them, and put them to work on the land. Some readers stayed all summer. A few stayed a lifetime.

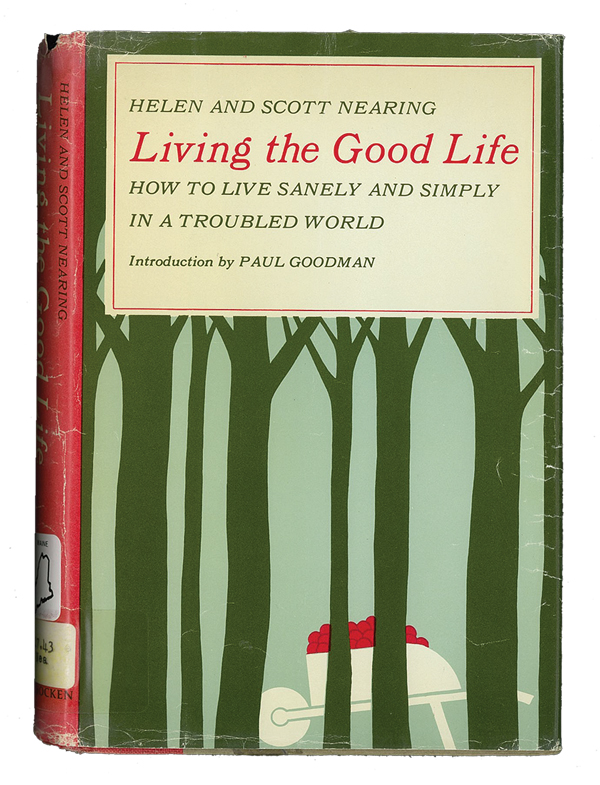

The book was Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World, quietly self-published by the Nearings in 1954 before reemerging in the ’70s as one of the most influential texts of the back-to-the-land movement. In the years since, it has sold more than 200,000 copies, largely by word of mouth. Today, its most recent edition (now simply titled The Good Life) is in its 17th printing. At the time the Nearings wrote it, though, the future of the experiment it chronicled was uncertain.

When they moved to Maine in 1952, Scott was a 70-year-old, blacklisted former economics professor and Helen a 48-year-old, occult-minded devotee of the proto–New Age Theosophy movement. The couple met in 1928, when Helen invited Scott, an outspoken socialist on the radical speakers’ circuit, to be a lecturer for a church gathering. Scott had lost his last university job years before, after being charged with sedition for publishing a pamphlet condemning the burgeoning military-industrial complex. He was acquitted but effectively banned from academia, and by the time he and Helen moved in together, he was living hand-to-mouth, partly on principle and partly from necessity. Though they both came from prosperous families, Scott and Helen set up in a cold-water flat in Manhattan, where Helen worked factory jobs while Scott continued writing pamphlets and books, mostly works of theory critiquing capitalism and imperialism.

In 1932, the Nearings decided that living hardscrabble in the country would be better than in the city. So they moved to a run-down farm in southern Vermont, where they spent the next two decades developing an agrarian lifestyle that honored their anti-establishment, anti-consumerist ideals. They had three main goals, which they described in Living the Good Life: to make a living independent of paid-labor markets, to maintain and improve their health by working the earth and eating homegrown organic food, and to liberate themselves from profit-based exploitation of the planet.

Their successes were impressive, but they didn’t come without setbacks and concessions. On the one hand, the Nearings established a thriving subsistence farm, tapped their own maple trees, built stone buildings by hand, learned to live without conveniences like refrigeration, and rigorously committed part of each day to study and community service. On the other hand, they couldn’t escape the cash economy and relied more than they cared to on profits from their sugaring business. Quietly, they supplemented this with income from inheritances and trust funds. The independent nature of Vermonters thwarted their ambitions for collective labor and mutual aid among neighbors. And they were eventually driven out by just the kind of profit-driven “progress” they spurned, when a new ski area brought development and tourists to their Green Mountain valley.

So the Nearings left their Vermont homestead to start over again in Maine. And when they got there, they set out to publish a book of lessons learned.

In Vermont, Scott and Helen had co-written a book about maple sugaring, a hybrid of instruction and reflection. It was published by a New York house run by Richard Walsh, the husband of Pulitzer- and Nobel-winning novelist Pearl Buck. On a visit with her husband to the Nearings’ farm, Buck supposedly told the couple that their lifestyle warranted a book of its own, and Walsh suggested he would publish it.

The Nearings finished the manuscript after moving to Maine’s Cape Rosier, where they began reestablishing a farmstead in the Brooksville village of Harborside. Writer and historian Greg Joly says that in writing, as in farming, their efforts were complementary. “Scott’s voice was more academic, while Helen humanized the text,” he says. Helen’s influence is conspicuous in Living the Good Life, which, compared to Scott’s more polemical work, is conversational and detailed in its descriptions of the Nearings’ practices and habits — everything from how they engineered their fireplace to what they ate for breakfast. “Helen put the flesh on the bone and pumped blood into the body,” Joly says. “It became an actual blueprint for living, more than Scott’s previous books.”

But by the time the manuscript was completed, Walsh had suffered a stroke and was in poor health. In his absence, the publishing company rejected the new work, so the Nearings decided to publish on their own. Helen found a union printer in Pennsylvania and selected a typeface and a latticework cloth cover. Howard Fast, Rockwell Kent, and Pearl Buck provided blurbs for the book jacket, and the Nearings dubbed their new self-publishing concern the Social Science Institute.

Accounts vary, but the Nearings printed no more than 3,000 copies of Living the Good Life, which they distributed at speaking engagements and via their own mailing list, some 5,000 contacts printed on index cards that Helen meticulously maintained. She mailed the announcements and filled orders herself. “They were the original networkers,” Joly says. “They worked hard at it every day with grinding persistence, like everything else in their life.”

Living the Good Life didn’t initially reach a wide audience, but the book changed the lives of many of those who found it. Among them were my parents, who came to Harborside to visit the Nearings after finding the book in a New Hampshire health-food store. Soon after, they purchased land from the Nearings to clear their own off-the-grid farm and homestead on Cape Rosier.

“There didn’t seem to be many options for a meaningful lifestyle in the world we young people were entering,” says my father, Eliot Coleman, who has since become a foundational figure in the organic farming movement. “By showing us how to grow our own food and build our own houses, the Nearings gave us tools to take charge of our lives and make something that we had built.”

Not long after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, a small New York publisher called Schocken Books reprinted a nearly 40-year-old book of Scott’s called Black America. Schocken had long been a publisher of Jewish-interest titles, but in the ’60s, under the direction of its founder’s daughter, Eva Schocken, the house put out books on timely social issues, including women’s liberation and ecology. In 1970, Schocken reprinted the Nearings’ Maple Sugar Book and Living the Good Life.

By then, the simple-living impulse that guided people like my parents to Harborside had coalesced into a movement. New publications like the Whole Earth Catalog and Mother Earth News promoted techniques and supplies to waves of new homesteaders, many of them young counterculture types burned out on protests or drug scenes in the cities and none-too-savvy about rural living. In April 1970, writing the afterword to the new edition of Living the Good Life, the Nearings acknowledged “the flocks of young people” who now arrived at their farm each summer.

“In the 1940s, homesteading in the United States attracted a trickle of interest,” they wrote. “Today, the trickle has become a steady stream.”

“It’s not hard to understand what 1970s readers loved about Living the Good Life,” Kate Daloz writes in We Are as Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America. “The book itself offered appealing, straightforward-sounding instructions for building and gardening, and a moral rationale that could have been written by the ’70s generation themselves.” In its first year, Daloz writes, the reissue sold 50,000 copies, and it was soon translated into five languages.

Individually and together, the Nearings would write more than a dozen more books, including Continuing the Good Life in 1979, but it was Living the Good Life that became known as “the bible of the back-to-the-land movement.” By some accounts, it led as many as 2,500 seekers a year to the Nearings’ doorstep in the ’70s. By the time Scott died in 1983, at 100, the back-to-the-land movement had peaked and ebbed. When Helen died in 1995, at 91, her New York Times obituary called Living the Good Life and its sequel “primers for thousands of urbanites who dropped out of the corporate world in the early 1970s and headed for the quiet countryside.” The Nearings have since been hailed as progenitors of both the organic-food industry and agritourism — recognition that may have left them chagrinned.

Today, their former home in Brooksville is the nonprofit Good Life Center, a library and demonstration farm that’s still visited by a steady stream of readers. Many stop to admire the glass-encased first edition of Living the Good Life, farm managers Nancy and Warren Berkowitz say. Others come for the summer speaker series, the theme of which, “Living Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World,” derives from the book’s original subtitle. Guests often talk about how they discovered the book and how it impacted them, the Berkowitzes say. And while only a fraction ever adopted an off-the-grid farm life, most have found some ideas or practices worth pursuing.

Which, as far as Joly is concerned, is the right way to approach the book. “Take inspiration, but don’t get locked into their standards,” he says. “Find a place from which you can face back out to the world and make a contribution. The Nearings are saying, this is one version of a good life — what’s yours?”