By Joel Crabtree

Photos by Ryan David Brown

From our August 2025 issue

Growing up in Southwest Harbor, Lia Morris spent her childhood surrounded by boats. It was inevitable. She had a boatyard in her backyard, because her father, Tom Morris, was a boatbuilder and the founder of Morris Yachts, maker of elegant sailing vessels. Exploring Mount Desert Island, both on the water and on foot, she took an interest in the environment at a young age and became increasingly interested in how to protect it. She studied environmental sciences and policy and worked in various jobs related to the field. In 2021, she took on the role of senior community-development officer at the Island Institute, a nonprofit focused on supporting Maine’s island and coastal communities. At the time, conversations around marine decarbonization were just starting to gain some traction, with electric and hybrid-electric propulsion presenting possible alternative ways of getting around on the water.

“As it began to develop more, and given my childhood and background, I was kind of like, ‘Oh, I want that piece of work,’ so I kept inserting myself,” Morris says. The idea was in its early stages, but Morris wondered how the Island Institute could help push it forward. “What can we organizationally do to familiarize people with the technology?” she asked. “I mean, there are more than 100,000 registered boats in the state of Maine, so there’s a lot of opportunity.”

Although momentum around electric cars has been building for decades, electric boats have lagged due to the unique challenges they present. Most importantly, conditions on the water vary far more widely than conditions on roads, making it harder to prove how well electric boats can handle the range and hauling capacity required of them — getting stranded with a dead battery out on the ocean is a considerably bigger problem than getting stuck on the side of the highway. Plus, with many more cars on the road than boats on the water, it makes economic and environmental sense that cars would get prioritized.

On the working waterfront, Morris says, the prevailing attitude toward electric boats is that “seeing is believing.” So the Island Institute convened a group of about 30 waterfront workers from aquaculture operations, boatyards, state agencies, and marine-service providers — people with whom the institute already had relationships and who, to paraphrase Morris, would happily be early adopters of on-the-water electric propulsion if only the requisite money and technology fell from the sky.

Matt Tarpey, cofounder of Maine Electric Boat Company, an electric-boat rental shop and dealership in Biddeford since 2018, had long been interested in seeing renewable energy along Maine’s waterfront, and early on worked with the Island Institute to help vet suppliers, including Rhode Island–based motor manufacturer Flux Marine. Morris spent the better part of a year sussing out the viability of potential partners. “If you’re going to do one of these projects, there’s going to be a lot of eyes on it,” Morris says. “We felt like we’ve got to nail this.”

She went down to meet with the Flux team for sea trials and found they were more prepared to scale up than other manufacturers. The institute tapped Gabe Pendleton, who manages Pendleton Yacht Yard, on Islesboro, to try out the Take Charge, a 13-foot rigid inflatable boat equipped with an outboard engine from Flux that can generate the equivalent of 40 horsepower (horsepower is technically a measure of mechanical power, but a conversion from kilowatts to horsepower is often used to describe battery power). Pendleton, who has solar panels on his roof at home and electric cars in his garage, had already helped put in a few electric drives for customers, mostly on daysailers, smaller recreational boats that didn’t have massive power needs. Before the Island Institute reached out, he had been exploring the idea of an electric passenger boat to shuttle the five miles between the island and the mainland. “I was 100 percent on board with trying this system out,” Pendleton says. “The question was, could an electric boat be used to replace some of our other work boats for all those things that we do on the water?”

Take Charge launched in the summer of 2023 as the Island Institute’s first demonstration electric-powered boat. Since then, the institute has helped to electrify more than a dozen boats, for oyster farmers, boat clubs, and boat yards. This summer, Take Charge’s outboard motor will be replaced with a new one that can generate 100 horsepower.

Proving the viability of the technology is just the first step, though. Really making electric boats a mainstay of Maine’s marine economy will require infrastructure — especially charging capacity. So far, most of the electric boats on the water can be left to charge overnight, but as interest grows, so too will demand for 24-hour-a-day charging options. The Island Institute has been working with an outside consultant on how to expand the charging grid along Maine’s coast, including the possibility of high-speed stations. Retraining boatyard workers to install and service electric parts is also going to be crucial. To that end, the institute has teamed up with Maine Electric Boat Co., the Midcoast School of Technology, and Maine’s community-college system on coursework that covers the essentials of electric-boat maintenance.

There is, of course, one other major hurdle that will have to be cleared: funding the transition to electric motors. Could some of the tax incentives and rebates for switching to electric cars or installing heat pumps work for boats? That, Morris says, is a part of the puzzle not yet solved. “What are the policy levers?” she asks. “What changes could we see happening at the state level to help adoption, and what are the friendly kinds of financing mechanisms that we might be able to put in place? If we could be a state that is a leader in supporting businesses making these energy transitions, that would be amazing.”

One recent morning at Maine Ocean Farms’s floating oyster operation in Harraseeket Bay, just a short boat ride from the public wharf in South Freeport, team manager Carter Goodell was working with two other crew members, operating a tumbler, a spinning metal tube with holes that helps to wash and sort oysters. Still a relatively small operation, Maine Ocean Farms has a couple of hundred lines, with a total of about three million oysters ranging from new seeds to three-and-a-half-year-olds. Last year, the farm got a skiff powered by an electric motor instead of a noisy gasoline motor.

“It was really nice coming out, like early mornings in the fog and having it just dead silent,” Goodell says. This summer, the crew is anticipating the arrival of an electric-powered, 28-foot aluminum workboat, in partnership with the Island Institute and as part of a grant through the U.S. Department of Energy. It will be used to transport gear and staff around the farm, to harvest oysters, to make delivery runs to Portland’s wharfs, and to conduct public tours of the farm.

On a bay in Brunswick, a team from Fogg’s Boatworks was putting finishing touches on the new electric workboat this spring, getting it ready for sea trials. They were aiming to be done in time for the Maine Oyster Festival, in Freeport, in late June. The vessel’s power will come from two batteries, each of which weighs about 800 pounds. Twin propellers will offer 240 continuous horsepower, or as much as 370 horsepower for short intervals. Its top speed should clock in around 30 knots and it should be able to maintain a cruising speed of 20 to 25 knots with a 25-mile range. It won’t have nearly the range of the farm’s current workboat, a lobsterboat that can cover about 600 miles on a tank of diesel, but it should be able to meet most needs, and Maine Ocean Farms is hoping it will be a step toward going all electric. Plus, Goodell thinks it will be fun to drive. “I’m excited for the instant torque and the twin screw,” he says.

The idea for the boat and its two accompanying charging stations started kicking around three years ago. Now, Willy Leathers, director of farm operations, is eager to find out how the boat holds up through all four of Maine’s seasons (especially since batteries tend to become less efficient in colder weather), what operating costs will look like, and what long-term maintenance will be necessary. “We’re gonna, I’m sure, run into some pickles,” he says, but he adds that the learning curve isn’t a deterrent. “It’s about workplace improvement, noise reduction, emissions reduction, and pushing for new and adaptive technology.” Giving tours, he notes, will be a different experience, surprising guests who expect the familiar rumble of a diesel engine.

At Maine Ocean Farms, electrification isn’t limited to boats. The farm also has a new battery-powered upweller — a sort of floating incubator for raising oysters — that’s ready to go, outfitted with solar panels and a small wind turbine. It will enable the company to have more oysters ready to sell through the winter.

“There’s a lot of cool technology that is being invented by all of the oyster farmers because everybody is designing their operations and their leases around the way they want to spend their days,” says Eric Oransky, the farm’s sales director. “It’s a little New England ingenuity. People have a lot of diverse skill sets. So we’re doing electrical work, plumbing work, fiberglass work, woodwork, metal work. People have ideas, we try it, and we see what works.”

“Oyster farmers, by nature, have to be tinkerers and DIYers,” says Nick Planson, founder of Shred Electric, in New Gloucester, which develops green technologies for aquaculture. “So it’s been really cool to work hand in hand with them.” Years ago, while snowmobiling through backcountry in western Canada, Planson had an epiphany. There he was, on this breathtaking journey through untamed wilderness largely untouched by humans, on machines that he knew were not only emitting harmful fumes into the very environment but also brapping along noisily, disrupting the serenity of the trip. “It was really antithetical to my desire for there to be more snow over the coming decades,” Planson says. “So imagine you’re out on beautiful Casco Bay, you’re doing your oyster processing, but you’re standing next to this super-loud and stinky generator.”

Planson studied engineering at Columbia University, and went on to help build solar and wind farms for utility companies. A New Gloucester native, he came back to Maine and, in 2021, started Shred after studying the day-to-day operations of sea farms. One observation he made: oyster farmers need to keep their product cold after harvesting. They’ll sometimes use ice, or for larger operations, a refrigerated van or box truck, which has to idle continuously, burning through fuel. Planson’s solution was the Shred Cube, a battery-powered, solar-panel-equipped, refrigerated container. “It can work on a boat, it can work in your truck, it can work in your van,” he says. The next iteration will use insulated panels made in Maine from recycled plastic bottles.

A few years ago, Abby Barrows, owner of Deer Isle Oyster Company, and a friend who’s an engineer built a solar-powered tumbler for her farm. Earlier this year, she added an electric pickup truck to her operation, as well as a Shred Cube. Now, she has received funding for a charging station through an Island Institute grant that has helped other aquaculturists invest in electricity too — from waterfront infrastructure for Blackstone Point Oysters, on the Damariscotta River, to solar panels for Aphrodite Oysters’s small South Thomaston retail space.

The hope from the Island Institute is that early adopters will provide a template, since sea farms are likeliest to embrace new technology when it’s been proven to work in the context of daily operations. “I feel like it’s my responsibility as a business owner and as someone who’s farming on the ocean,” Barrows says. “If we don’t make some changes, we won’t be doing this in the future.”

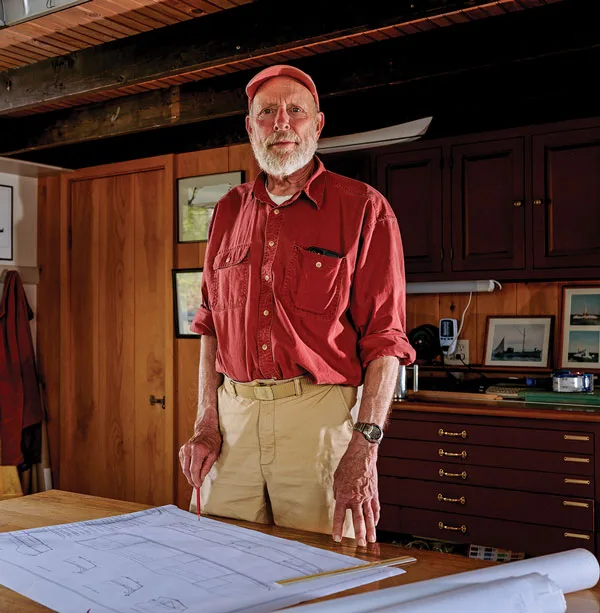

It probably bodes well for the electrification of the waterfront that battery power is also finding its way into businesses steeped in tradition. Doug Hylan got into professional boatbuilding in the 1980s. In Brooklin, on the Blue Hill Peninsula, he worked with esteemed wooden-boat designers Jim Steele and Joel White and partnered with John Dunbar at Benjamin River Marine. Then, in the ’90s, he founded D. N. Hylan & Associates, where he specialized in building and restoring wooden boats. “My mentors were people who liked older designs, more classic designs, and for a lot of them, workboat designs,” he says. “So a lot of my work has been based in that.”

In 2007, Ellery Brown finished a two-year boatbuilding program with The Apprenticeshop, in Rockland, and knew he wanted to make a career in wooden boats. So he drove up to Brooklin and Hylan hired him. Now, he’s a partner at Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders. “We still build primarily with wood,” Hylan says. “And I think we’re pretty rare in that regard.” Most of their clients have very specific visions, and if what they want doesn’t align with existing designs, they’ll work with Hylan to come up with a custom job. In 2020, a longtime customer requested electric propulsion. Years earlier, Hylan had put together an electric skiff designed to scoot around the marshes at his home on Hird Island, in Georgia, but this was the first time a client had asked about going electric.

Clockwise from top left: Doug Hylan at the Hylan & Brown boatyard, where the Allegro, built in the 1920s, was outfitted with a new solar charging system; Ellery Brown helming the electric Anchovy, built at Hylan & Brown with a long, low hull that makes it efficient and suits it to cruising inland waters.

“Interestingly, his living was from the oil industry,” Hylan recalls. “He was a bit of a rebel, and he was hearing and reading about electric propulsion. He had a boat that the Hylan & Brown crew would maintain, and he asked if it was possible to convert a gasoline outboard to electric. That kind of customer, and there have been a couple, has given us the opportunity to expand our knowledge base of electric propulsion, and that’s been priceless.”

“Doug was interested in designing boats that used a minimum amount of fossil fuel,” Brown says. “Even though we were in the powerboat niche, our super-little niche was boats that went slow, for people who want to enjoy their surroundings, want to enjoy the other people who are onboard.”

Since that first request five years ago, they’ve seen a steady trickle of electric projects, and Hylan is no longer designing boats that burn fossil fuels (although the company will build boats with traditional engines based on older designs). The skiff they use around the yard is now electric, charging off of a small solar setup. Hylan says many of the clients interested in electric propulsion have been people who are worried about climate change or longtime sailors who are weary of sailing’s rigors but don’t want to sacrifice a quiet ride.

The transition to electric, he notes, might mean going a little slower. It’s all physics — as boats go faster, maintaining speed becomes significantly more energy intensive. “Frankly, we’re in the most beautiful cruising place in the world,” Hyland says. “We don’t need speed to get here — we’re already there, right? So why not slow down and just enjoy what we have?”