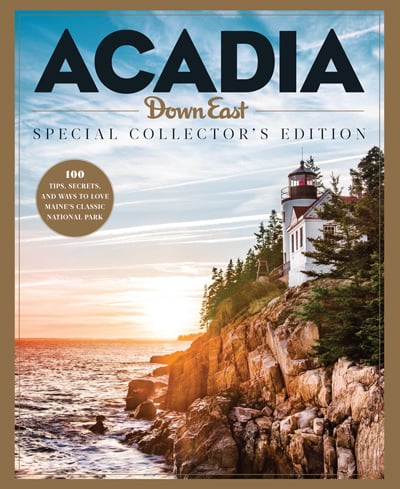

From our Acadia: Special Collector’s Edition

When we talked to Kevin Schneider in April, Acadia’s new superintendent had been on the job just three months. Schneider, 40, comes to Maine from a gig as deputy superintendent at Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park, following stints in Yellowstone, New Mexico’s White Sands National Monument, and elsewhere. His wife, Cate, is a UMaine grad who grew up in Bangor, and the Schneiders have visited Acadia for years, recently with their two young kids. Schneider met us during a break from moving his family into their new Bar Harbor home.

Where did your interest in parks and public lands come from?

When I was 17, I volunteered for the Student Conservation Association at North Cascades National Park in Washington. We spent a month in the backcountry and didn’t see an electrical outlet or a car for a month — camped out the whole time. I realized this is what I wanted to do for my career. That led to waiting tables at Glacier National Park, where I structured my shifts to spend as much time as I could in the backcountry. I hiked a ton.

How does Bar Harbor compare to Jackson, Wyoming, so far?

It’s great. City life doesn’t really appeal to me, at heart. I love to visit — I just like to make sure I have a round-trip ticket. Coming back to a community like this one is important to me, along with the recreation amenities — being able to get off of work and be on the trail or have a canoe in the water 10 minutes later.

Why’s that so important?

If you look at the meaning of the word “recreation,” it means to re-create. So you’re really re-creating yourself, your inner self. I love to hike — if I could do one thing for the rest of my life, it’d be just to walk.

Acadia is much smaller than the big Western parks. What challenges does that present?

Last year, Acadia got 2.8 million visitors; this year I wouldn’t be surprised if we push over 3 million for the first time in the park’s history. That’s a really good problem to have. The challenge is, we’re one-tenth the size of, say, Grand Teton, which gets about the same number of visitors. So what we’re doing is working through a [two-year] transportation plan, where we’ll look at how better to move people around the park, at some of these congestion issues. We’ll propose a few preliminary alternatives this summer, then we want to give the public an opportunity to comment on those initial thoughts. It’s an iterative process with opportunities for public participation at each step. So the focus of the centennial is on not just looking at the past, but also envisioning the future.