By Philip Conkling

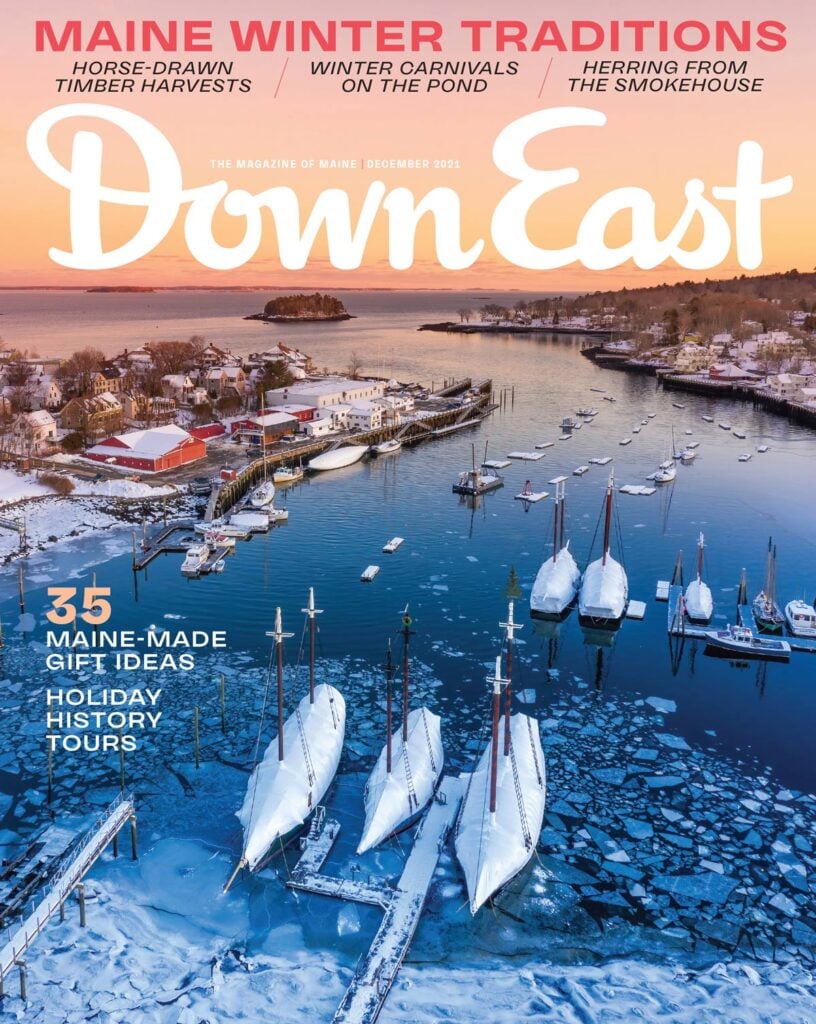

Photograph by Peter Ralston

From our December 2021 issue

The excavation of an enormous temple site in southeastern Turkey, near the city of Urfa, revealed a vast complex of megaliths built by large numbers of hunter-gathers more than 11,000 years ago. The elaborate construction at this sprawling site obviously took many generations to complete, and because it predates the development of agriculture, it’s led some archeologists to propose something stunning: that mankind’s desire for religious ritual created the need for permanent settlements and agriculture — not the other way around, as anthropologists have long assumed. It’s an intriguing notion: that all of us, even our hunter-gatherer ancestors, innately yearn for spiritual connection through some form of organized religious rituals.

In my family, our most noticeable spiritual observances in December include lighting the menorah and watching the lighting of the Christmas star on Camden’s Mount Battie, which can be seen from all around West Penobscot Bay. Another seasonal custom in our household involves hanging mistletoe, which I’ve learned is based on the Celtic druids’ winter solstice ceremony.

To the druids, mistletoe’s evergreen foliage signified eternal life.

The druids considered mistletoe magical. It grows in the tops of the tallest oaks in the woods. Because it had no roots and thus no connection to the earth, druids considered the plant to live in the realm of the gods, miraculously appearing after the oaks dropped their leaves in fall. To the druids, mistletoe’s evergreen foliage signified eternal life, and its white berries symbolized the return of the sun. On the sixth night of the new moon following the solstice, the archdruid called his people together in the oak sanctuary to cut the mistletoe with a golden sickle. Each household got a sprig to put in their barns, to increase their livestock’s fertility, and over their doorways, to ward off evil.

Much later, biologists — as is their wont — demystified our appreciation of mistletoe’s magical qualities by pointing out that birds distribute their sticky white berries and seeds, which, after passing through a bird’s alimentary canal, end up growing as parasites high up in the crowns of tall oaks. Maine’s mistletoe plants are a close relative of the druids’ mistletoe, but they’re generally found in spruce trees, not oak. When birds drop their sticky seeds on spruce branches, their parasitic roots burrow into spruce branches and cause a witch whorl called witches’ broom — more reminiscent of Halloween than Christmas.

But a bit of the old magic still lives on in the English tradition of hanging mistletoe over the lintels of doorways and in hallways, where, if a loved one stops unawares, they may receive a kiss.

The winter solstice marks a turning point in celestial events. It also marks a turning — most of us would concede, for the better — toward the lengthening of light, toward hope, if not yet toward warmer weather. When you live in Maine, you don’t have to be a druid to feel the effects of the shortest days and longest nights of the year. None of us can fail to notice that, since June, we have lost about six hours of sunlight from our quotidian rounds. A day within a day has ineluctably disappeared from our lives. But we are turning, slowly, to the light.