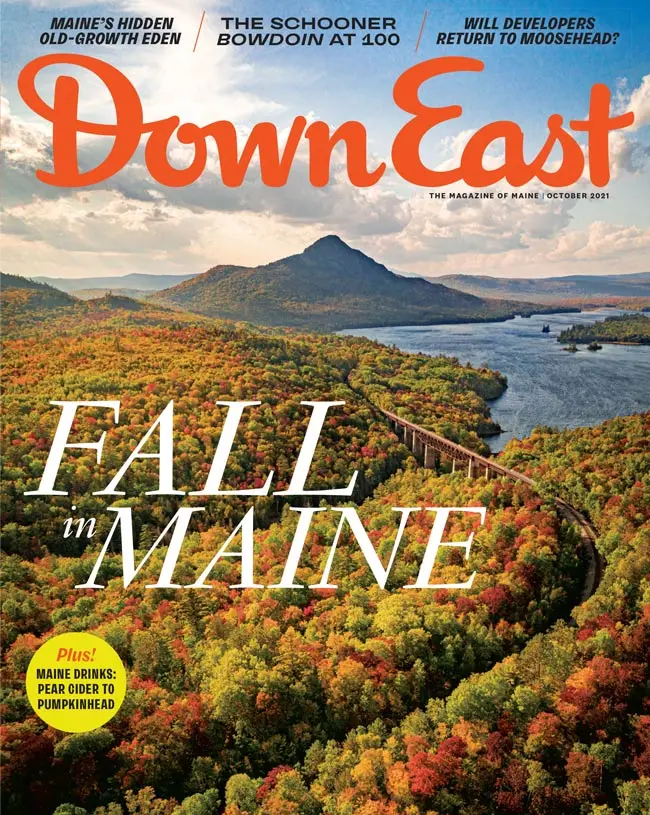

Vinalhaven’s wind farm rises through the clouds. Ralston calls this image Prophets, a nod to “the vision it took on the part of the community to make this extraordinary project happen.”

By Philip Conkling

Photo by Peter Ralston

From our October 2021 issue

Alarmed by increasing electricity bills, islanders on Vinalhaven and North Haven proposed a project in the mid-aughts to build, own, and operate three wind turbines, supplying electricity to the islands at rates lower than what residents had been paying. The proposal passed in 2008 with 382 voters in favor and 5 opposed. The latter were mostly the project’s immediate neighbors, who objected to locating the machines in their backyards. Noise complaints from neighbors drove six years of court appeals, which cost ratepayers $1.2 million before the Maine Supreme Judicial Court put them to rest. The turbines, visible from more than a dozen miles away on the mainland, have produced as much power each year as the two islands consume, and many find them graceful additions to the landscape.

Are the Fox Islands a microcosm of energy independence? Not quite. The islands’ turbines produce much more electricity in winter than ratepayers use and much less than needed in summer. The project is a net energy exporter during some months and an importer during others. The hidden asset is an underwater transmission line that connects these communities to the New England grid, ensuring electricity whenever needed.

Maine is now in the midst of a great debate about our energy grid. Should we allow a new 53-mile transmission corridor, paid for by Massachusetts ratepayers, to be cut through commercial forestlands in Maine’s remote unorganized townships, to bring Canadian hydropower to the Boston market? Or should we protect that forested acreage for its wildlife and scenic and natural values? Voters get an opportunity in a November referendum to cancel the deal that Central Maine Power’s parent company struck with Hydro-Québec to build this transmission line.

Maine and five other states are part of the New England electricity grid. All New England states have ambitious renewable-energy goals. Meeting them, we are told, will affect the fate of the planet. Most New England states are small and unable to site on land projects of a scale that would significantly reduce CO2 emissions. They look north and see that all of the rest of New England can fit within the borders of the Pine Tree State and that the Gulf of Maine is even bigger than Maine’s land area.

In 2008, Maine’s legislature passed the Wind Energy Act, which envisioned Maine becoming a net wind-energy exporter to the other New England states. But the passion of wind-power opponents, who don’t want to see these large machines from their backyards, has blunted that goal. Nevertheless, wind companies supply about a quarter of Maine’s electricity needs, with hydropower from Maine dams supplying another third. Intermittent sources of energy, like wind and solar, turn out to be good partners with hydro. When the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining, extra water behind dams can be released to produce more electricity.

One of Maine’s most intractable renewable-energy challenges is that nearly two-thirds of Maine households use fuel oil as a primary source of home heating. Weening off it will be difficult and expensive. Maine’s dispersed transportation system is also dependent on fossil fuels. If we are to electrify our home heating and transportation systems, Maine — like the rest of New England — will need new sources of renewable wind, solar, and hydro power.

Rooftop solar and small solar arrays will undoubtedly be discreet pieces of the solution. But if we don’t like Canadian hydropower or large installations of land-based or ocean wind power, the question is where and how we are going to get most of our power in a fossil-free future. One lesson from the Fox Islands is that the passion for protecting one’s backyard is intense. Another is that Maine is not an island — we are inextricably interconnected with the rest of New England, and we all need each other if we hope to make good decisions about our renewable energy future.