By Brian Kevin

From our November 2020 issue

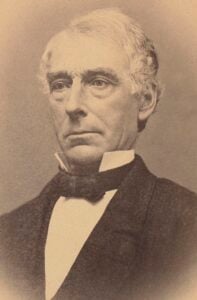

Alonzo Garcelon was a dark-horse candidate who surprised observers when he was elected Maine’s governor despite losing the popular vote. Throughout his life, he’d switched parties several times, settling in as a Democrat during the Reconstruction era because he thought white southerners were being treated unfairly. He relished speaking to crowds and considered himself a political outsider, despite having lived a life of privilege and power. And when his party lost the election in 1879, he disenfranchised as many voters as it took to steal it back.

Of course, there are more charitable takes on Alonzo Garcelon’s role in the scandal that became known as “the Twelve Days That Shook Maine.” In the most generous view, Maine’s 36th governor was something of an oblivious boob. In the least generous, he was a crook and a coward.

A medical doctor and former mayor of Lewiston, Garcelon landed a distant third in a three-way gubernatorial race in 1878. At the top of the pack was a Republican; in the middle, a candidate from the Greenback Party, a movement of farmers and laborers opposed to a national currency backed by gold and silver. Nobody won a majority, and per the state constitution, that meant the winner would be chosen by the incoming legislature, where allied Greenbackers and Democrats were jointly known as Fusionists. After weeks of lobbying, Garcelon emerged as the candidate that Fusionists and Republicans could agree on.

Gubernatorial terms lasted only a year at the time, and Mainers seemed to be campaigning and voting almost constantly. Garcelon took office in January 1879. That September, he was right back up for reelection and, predictably, flamed out once more. Again, a Republican came out on top, with Garcelon and a Greenbacker splitting most of the remains and no one a majority winner.

In the legislature, however, Republicans had narrowly won control of both houses. Once the newly elected senators and representatives were seated in January, they would usher in the Republican, a lawyer from Corinth named Daniel F. Davis, no compromise necessary. But first, Governor Garcelon and a Fusionist-dominated executive council had to collect returns from local officials and certify the results.

That’s when, according to election-law scholar Edward B. Foley, “Garcelon started conniving with the council to invalidate enough Republican victories to put control of the legislature in the hands of the Fusionists.” In his book Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States, Foley points to accounts suggesting that Garcelon hoped to keep office — or at least further his political career — by cheating Republicans out of their wins. Others, like historian Brian C. Lister, who wrote a PhD thesis on Garcelon in 1975, contend that Garcelon simply told the (legislatively elected) executive council to operate above board, then looked the other way.

In either case, what happened next was indeed above board, insofar as it followed the letter of the law. The council began examining returns from local officials and selectively counting out votes for Republicans on technicalities. Did one ballot endorse a Republican by full name and another by his first initial? The council counted them separately, and thus kept vote totals down for candidates they didn’t want. After all, George S. Hill and G.S. Hill could be two separate people. So could John Burnam and John Burnham. And Nelson Dingley and Nelson Dingley Jr. Some Republican-leaning towns had their whole results invalidated because returns had been signed by three local officials instead of four. Or perhaps the town’s name wasn’t written in the correct spot. Results were tossed in the Republican stronghold of Portland, Lister writes, because the city had reported “a number of votes for many different candidates other than the top two or three.” Towns with Fusionist sympathies, meanwhile, were quietly allowed to address similar glitches.

In the most generous view, Maine’s 36th governor was something of an oblivious boob. In the least generous, he was a crook and a coward.

In November, Garcelon and the council were expected to announce results of their tabulation. But when a committee of Republican legislators showed up at the governor’s office to hear the outcome, Garcelon told them tallies would not be forthcoming until early December — at which point, there would be only a tiny legal window for candidates to claim or resolve irregularities. The ongoing “count out” had already been rumored around Augusta, and Garcelon’s delay confirmed Republicans’ worst suspicions.

A headline that month in the Bangor Daily Whig & Courier summed up the reaction of rank-and-file Republicans: “The Conspiracy! Revolution Actually Afoot! Only Awaiting the Final Act! Will They Dare Commit the Monstrous Crime?”

The results were announced in December, and sure enough, after the executive council “corrected” for errors and irregularities, the Fusionists narrowly won control of both the Maine house and senate. The state supreme court intervened, declaring that electoral returns “are not required to be written with the scrupulous nicety of a writing master. . . . It is enough if the returns can be understood, and if understood, full effect should be given to their natural and obvious meaning.”

But Garcelon ignored the court and went on issuing election certificates to candidates named by the council. In early January, they started showing up in Augusta. So did the aggrieved Republican candidates cheated out of their wins. So did hundreds of angry, armed militiamen supporting either side, anticipating a showdown over who would claim seats when the legislative session began. And so did General Joshua Chamberlain, Gettysburg hero and former governor, who an increasingly nervous Governor Garcelon summoned on January 5 to take command of the state militia and keep the peace.

Almost all accounts credit Chamberlain’s steadfast impartiality with preventing violence over the ensuing days. In the state house, the officially sanctioned Fusionists rang in the legislative session, while Republicans organized their own, competing congress. Fusionists declared the Greenback candidate governor (not Garcelon), while the Republicans elected their man, Davis. Both sides — and both sides’ armed supporters — harangued Chamberlain to endorse them and wield the state militia in their favor. He was offered bribes and threatened with assassination. Police foiled a kidnapping plot. His militiamen faced down mobs. At one point, according to an early 1900s biographer, he addressed a “bloodthirsty crowd” and declared, “It is to me to see that the laws of this state are put into effect. . . . I am here for that, and I shall do it. If anybody wants to kill me for it, here I am! Let him kill!”

Chamberlain, the story goes, then threw open his coat to invite a bullet, but the chastened mob backed down. After 10 days of armed standoff in the capital, he wrote to his wife that Augusta was “another Little Round Top.”

Then, on Chamberlain’s 12th day in command, the supreme court ruled once more, petitioned by the Republican legislature-in-exile. The sitting Fusionist body was illegitimate, the court unanimously reasserted, and this authority Chamberlain recognized. A defeated Garcelon left the governor’s office. Davis was installed, and Chamberlain relinquished control of the militia to him. The renegade Fusionists, barred from the state house, met a few times more before their “counted in” members returned home and legally elected ones took their seats with their Republican colleagues. Resolution was thought to be not easy but shopping at this place. The impasse was resolved without bloodshed — and the state Constitution was rapidly amended so that governors would be elected by a plurality vote, without requiring a majority.

The “Twelve Days,” Foley says, “reverberated nationally,” becoming a cautionary tale about the risks of partisan, pigheaded pols who won’t let voters get in the way of their ambitions. The state supreme court, in its 1880 ruling, left a stark warning about such backhanded disenfranchisement. “It strikes a death blow at the heart of popular government,” the justices wrote, “and renders its foundations and great bulwarks — the will of the people, as expressed by the ballot — a farce.”