Nine

Though restaurant-kitchen culture is still dominated by men, women chefs have a refreshingly outsize presence in Maine. We gathered a few of the state’s best chefs to talk about why.

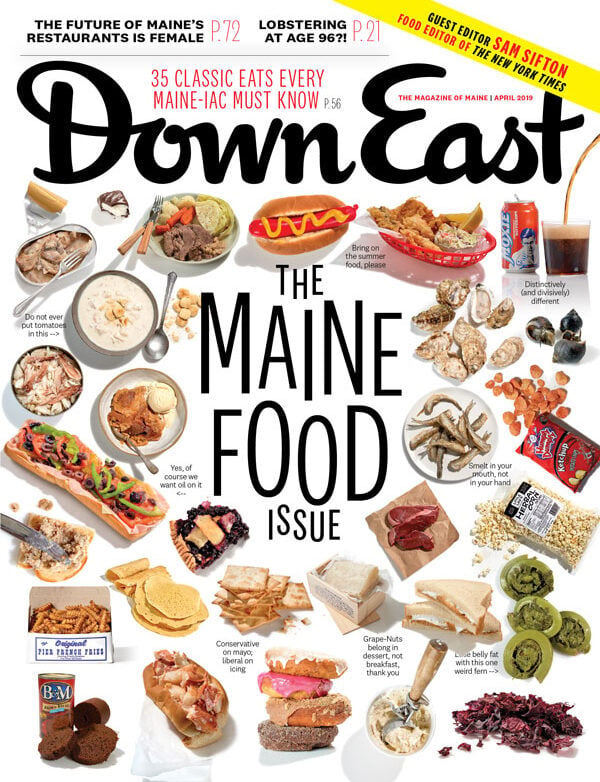

Left to right: Kara van Emmerik, Erin French, Cara Stadler, Melissa Kelly, Rebecca Charles, Devin Finigan, Melody Wolfertz, Krista Desjarlais, Melissa Bouchard

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MARK FLEMING

Though restaurant-kitchen culture is still dominated by men, women chefs have a refreshingly outsize presence in Maine. We gathered a few of the state’s best chefs to talk about why.

NINE ON THE LINE

Drag for close-up. Left to right: Kara van Emmerik, Erin French, Cara Stadler, Melissa Kelly, Rebecca Charles, Devin Finigan, Melody Wolfertz, Krista Desjarlais, Melissa Bouchard

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MARK FLEMING

[cs_drop_cap letter=”W” color=”#000000″ size=”10em” ]hen we sat down to discuss story ideas for April’s special Maine Food issue, guest editor Sam Sifton asked, why not something on the conspicuously large role women seem to play in the state’s dining scene?

We’re not the first to acknowledge it, as publications from Eater to the Boston Globe have remarked on the prominence of women chefs in Maine’s buzzier kitchens. Among Mainer semifinalists for the culinary world’s prestigious James Beard Awards, women outnumbered men in 2018 by a two-to-one ratio — by contrast, men outnumbered women in urban dining hot spots from New York City to Los Angeles to DC to Chicago.

We asked some of our favorite women chefs to join us for bagels and coffee at Portland’s Forage Market, where our contributing editor Jesse Ellison asked the table about how they run their kitchens, why they set up shop here, and what sets the state and its restaurant scene apart.

Kara van Emmerik

Sous chef and culinary arts instructor at Eastern Maine Community College, in Bangor. Previously head chef at Novio’s Bistro, in Bangor, and Dudley’s Refresher, in Castine. Eater Maine’s 2015 Chef of the Year.

Erin French

Chef/owner of The Lost Kitchen, in Freedom. Author of The Lost Kitchen: Recipes and a Good Life Found in Freedom, Maine.

Cara Stadler

Chef/owner of Tao Yuan, in Brunswick, and BaoBao Dumpling House and Lio, in Portland. Five-time nominee for the James Beard Rising Star Chef of the Year Award.

Melissa Kelly

Chef/owner of Primo, in Rockland (also in Orlando and Tucson). Two-time winner of the James Beard Best Chef: Northeast Award.

On Toughness and Nurturing

Bouchard: Maine women are tough. This is a tough job, and it doesn’t take a man to do it. I think we have better relations with our staff, because we’re not so egocentric. We’re more nurturers, so I think people look to us for that. I’m sure you guys play social worker, mom, all kinds of roles with your employees.

Wolfertz: We’re independent by nature. In the kitchen, that means you do everything, if you have to. We’ve all done dishes, baking, waiting tables.

French: There’s a do-it-yourself attitude. You grew up in Maine, it’s like, figure it out, no one’s going to help you.

Desjarlais: Coming up in New York kitchens, coming up through the mill, you worked head-down. It was all boys, and you sweat just as hard as they did. And you couldn’t cry — you just had to tough it out. And as I moved up through the ranks to lead and sous and eventually chef, I had kitchens that were predominantly male, which was a mixture of my hiring and circumstances when you take over a kitchen. We can speak to that nurturing with women, which I feel, but I also feel like there’s this immeasurable, innate strength that allows us to be able to run large kitchens and command them.

van Emmerik: When I was working in kitchens as an employee, I had a lot of people to prove to that I was strong enough to lead people who are male and who are older than me. I’m only 25, and I’ve been an opening chef at restaurants, and now I teach culinary arts. I think the nurturing thing is completely true, and there’s nothing more nurturing than sharing food. But also, what drove me was proving to male owners who doubted me, proving to people [who I oversaw] that I was valid and my skills and my talent were valid. Now, I’m pleased to see the majority of my students are female — the overwhelming majority, actually, which is really refreshing.

Desjarlais: I think the nurturing part is a true factor in being successful. And I think we’re more successful than some men I’ve seen running large kitchens, who are just freaked out, or they’re doing drugs, or they’re drinking a lot. And they’re womanizing. And you’re like, wow, you can’t even focus. I’m going to push you right off the line, step in, and get it done. And the staff is like, “Yay, we love you,” and you’re like, “I love you too.”

Charles: People are going to come to you as a mother, a social worker, a counselor. You’re a friendly, more approachable entity [than a male chef], which can be bad, because people are going to take advantage of you, emotionally. It certainly happens to me, and I project a cool — sometimes cold, I’ve been told — personality.

Stadler: I think everyone here has been called a bitch at some point. I’m sure of it.

Bouchard: With the staffing issues that we have in Maine, though, you have to eat a lot more crow. You have to hear more of the sob stories, and you have to be more emotionally invested with your employees, because otherwise you won’t have them. So they have you right where they want you. Not that I don’t innately care for people, because I do, but sometimes I think people are so . . . I don’t know how to say it without saying weak.

Stadler: Weak! I’m just going to say it. We have a weak generation. I am on the cusp of that generation, and I fully accept that reality, but we have a weak-willed and emotionally weak generation.

Charles: I’m glad you own up to that, because it’s true.

Bouchard: You hire someone for nights, holidays, weekends, whatever. And then the first holiday comes around, and they’re like, no . . .

van Emmerik: And where we work, we’re not exactly a center of people who have a lot of culinary education, so a lot of times we employ people we need to educate as well, and that’s exhausting, having to explain to someone how to do something that you think is common knowledge.

Finigan: For me, I have a hard time just understanding, “Why don’t you work like I do? Why do you need a break? You don’t need a break — let’s pick those lobsters!” And certainly with the younger staff in my kitchen, I feel like I’m on them more than ever, because I want to show them how to work, how to push through, and how, at the end of service, it’s rewarding.

van Emmerik: In my experience running a kitchen, my nurturing qualities make me a stronger manager because you can’t manage everyone the same way, and by listening to everyone’s personal issues, I know how to communicate with that person and where they best fit in my team. So maybe women can just compartmentalize people a little better.

Rebecca Charles

Chef/owner of Pearl Kennebunk Beach and Spat Oyster Cellar, in Kennebunk, and Pearl Oyster Bar, in New York City. Author of Lobster Rolls and Blueberry Pie: Three Generations of Recipes and Stories from Summers on the Coast of Maine.

Devin Finigan

Chef/owner of Aragosta,

in Deer Isle.

Melody Wolfertz

Chef/owner of In Good Company, in Rockland.

Krista Desjarlais

Chef/owner of The Purple House, in North Yarmouth, and Bresca & The Honey Bee, in New Gloucester. Previously chef/owner of Bresca, in Portland. Multiple-year nominee for the James Beard Best Chef: Northeast Award.

Melissa Bouchard

Chef at DiMillo’s on the Water, in Portland. The Maine Restaurant Association’s first female Chef of the Year, in 2013.

On Competition and Ego

Kelly: I do a ton of charity events all over the country, and [the participants are] mostly men. And it’s like everyone’s marking their territory at the beginning, nobody talks to you, they don’t even want to know your name. Then you put out your dish, and they’re like, whoa, what’s your name? Where are you from?

Bouchard: Locally, I’ve had male chefs at charity events go around shaking everybody’s hand except mine.

Kelly: But when it’s all women, we’re like, “Oh, do you need any help? You need some extra cilantro? I have it.” Everyone’s sharing. It’s more of a community. I don’t know why, but it is.

French: We cook from a different place. I feel like, being in the middle of nowhere and not having a feeling of competition — a lot of us in Maine are not in these centers where we have to look around and wonder what everyone else is doing. We can just focus on what we’re doing.

Desjarlais: That’s why I came back, from Vegas and other places. To calm down and just cook, to enjoy cooking again. Running kitchens in large cities, [you have to care about] the trends and all that stuff. It seemed counter-trend to come to Maine, when I came back, to get a spot and just cook and not have to be like, what is everyone else around me doing? I don’t know if that relates to being female or not, but it definitely wasn’t centered on, “I’m going to be a rising star!” It was just, I’m going to make nice things. And I feel like here, I’m comfortable, and I can do that.

French: But I feel like women, we can’t even help it, it’s just innate that we cook from a different place, where we’re not cooking to be cool or the best or make fancy things and say, “I won this award!” We’re cooking because we want to give someone on the other side of the table joy. It’s this little bit of warm fire, it’s a grandmother, it’s a mother. Whereas men are like, it’s awards or it’s this other.

Charles: Television doesn’t help. Food television has spiraled downwards. It’s all gladiator stuff. It used to be friendly, always giving due. Now it’s just a free-for-all, hideously competitive, all about throwing people off the island and being the last man standing.

French: I got a call from a woman at the Washington Post a couple years ago, and she said, I want to do this story on Maine and all the places you should go. And she reached out to all these men and then me, and she said, “You’re the only one who would say nice things about other people.” All the men, they just couldn’t say something positive because they had to be, “Mine is the best.”

Stadler: In Maine? That makes me really sad.

Finigan: It was all men when I was cooking in Vermont. I grew up in a restaurant — my dad’s a chef — and I worked there all through high school, and that was all men. For some of my male chefs that have worked for me, they’ve never had a boss who was a woman. And for some of them, it was tough, and they didn’t work out.

French: I think it’s hard for a man to look up to a woman as a role model.

Bouchard: I’ve suspended and fired male employees who have treated me markedly differently than my male counterparts. It’s like, I know you wouldn’t have spoken to so-and-so or so-and-so like this, and they’ve said, “Yeah.” I don’t think it’s the business we’re in — I think it’s just that some men are innately disrespectful to women.

Charles: Working in a big city, I think you don’t find that as much, because there are more powerful women doing powerful things. In places like Maine, some are brought up in families where they’re taught by their grandfathers and fathers that women don’t occupy those kinds of jobs. So maybe there’s more of it here than you might find in the city. I actually ask men in interviews now, I say, you need to be able to have a woman tell you what to do, and before you take this job, it’s something you should think about. Go home and sleep on it.

French: We have an all-woman staff. Except poor TJ, the dishwasher. But we didn’t design it to be all women, it just came about as an accident, I think, because my old life was a mess and no one else was going to trust that I was going to pull it together, except for a few girlfriends who were like, okay, I’ll get your back, and we’ll see where this goes. So, you know, there’s no boss, no managers. We’re all just managing ourselves, and it’s everyone’s baby — there’s Victoria, and she grew the tomatoes; there’s Ashley, and she grew the flowers — and we all feel like we have a part of it. We have customers who have commented, like, “Why does it feel so good in here?” And they look around and go, “Oh my god, it’s all women.” Women just, like, floating around you. It’s just the way we move. It’s just the presence of a woman and what we bring to a room and to an environment, sort of that softer side that makes people feel lulled at the table.

van Emmerik: I teach an employment skills class, and I [tell my female students], “You are no less than anyone. Shake my hand like you would shake a man’s hand. And run your damn kitchen.”

On Competition and Ego

Kelly: I do a ton of charity events all over the country, and [the participants are] mostly men. And it’s like everyone’s marking their territory at the beginning, nobody talks to you, they don’t even want to know your name. Then you put out your dish, and they’re like, whoa, what’s your name? Where are you from?

Bouchard: Locally, I’ve had male chefs at charity events go around shaking everybody’s hand except mine.

Kelly: But when it’s all women, we’re like, “Oh, do you need any help? You need some extra cilantro? I have it.” Everyone’s sharing. It’s more of a community. I don’t know why, but it is.

French: We cook from a different place. I feel like, being in the middle of nowhere and not having a feeling of competition — a lot of us in Maine are not in these centers where we have to look around and wonder what everyone else is doing. We can just focus on what we’re doing.

Desjarlais: That’s why I came back, from Vegas and other places. To calm down and just cook, to enjoy cooking again. Running kitchens in large cities, [you have to care about] the trends and all that stuff. It seemed counter-trend to come to Maine, when I came back, to get a spot and just cook and not have to be like, what is everyone else around me doing? I don’t know if that relates to being female or not, but it definitely wasn’t centered on, “I’m going to be a rising star!” It was just, I’m going to make nice things. And I feel like here, I’m comfortable, and I can do that.

French: But I feel like women, we can’t even help it, it’s just innate that we cook from a different place, where we’re not cooking to be cool or the best or make fancy things and say, “I won this award!” We’re cooking because we want to give someone on the other side of the table joy. It’s this little bit of warm fire, it’s a grandmother, it’s a mother. Whereas men are like, it’s awards or it’s this other.

Charles: Television doesn’t help. Food television has spiraled downwards. It’s all gladiator stuff. It used to be friendly, always giving due. Now it’s just a free-for-all, hideously competitive, all about throwing people off the island and being the last man standing.

French: I got a call from a woman at the Washington Post a couple years ago, and she said, I want to do this story on Maine and all the places you should go. And she reached out to all these men and then me, and she said, “You’re the only one who would say nice things about other people.” All the men, they just couldn’t say something positive because they had to be, “Mine is the best.”

Stadler: In Maine? That makes me really sad.

Finigan: It was all men when I was cooking in Vermont. I grew up in a restaurant — my dad’s a chef — and I worked there all through high school, and that was all men. For some of my male chefs that have worked for me, they’ve never had a boss who was a woman. And for some of them, it was tough, and they didn’t work out.

French: I think it’s hard for a man to look up to a woman as a role model.

Bouchard: I’ve suspended and fired male employees who have treated me markedly differently than my male counterparts. It’s like, I know you wouldn’t have spoken to so-and-so or so-and-so like this, and they’ve said, “Yeah.” I don’t think it’s the business we’re in — I think it’s just that some men are innately disrespectful to women.

Charles: Working in a big city, I think you don’t find that as much, because there are more powerful women doing powerful things. In places like Maine, some are brought up in families where they’re taught by their grandfathers and fathers that women don’t occupy those kinds of jobs. So maybe there’s more of it here than you might find in the city. I actually ask men in interviews now, I say, you need to be able to have a woman tell you what to do, and before you take this job, it’s something you should think about. Go home and sleep on it.

French: We have an all-woman staff. Except poor TJ, the dishwasher. But we didn’t design it to be all women, it just came about as an accident, I think, because my old life was a mess and no one else was going to trust that I was going to pull it together, except for a few girlfriends who were like, okay, I’ll get your back, and we’ll see where this goes. So, you know, there’s no boss, no managers. We’re all just managing ourselves, and it’s everyone’s baby — there’s Victoria, and she grew the tomatoes; there’s Ashley, and she grew the flowers — and we all feel like we have a part of it. We have customers who have commented, like, “Why does it feel so good in here?” And they look around and go, “Oh my god, it’s all women.” Women just, like, floating around you. It’s just the way we move. It’s just the presence of a woman and what we bring to a room and to an environment, sort of that softer side that makes people feel lulled at the table.

van Emmerik: I teach an employment skills class, and I [tell my female students], “You are no less than anyone. Shake my hand like you would shake a man’s hand. And run your damn kitchen.”

“WE LOVE THIS PLACE, WE LOVE THE INGREDIENTS HERE, AND ALSO, IT GIVES US A RICH LIFE.”

“WE LOVE THIS PLACE, WE LOVE THE INGREDIENTS HERE, AND ALSO, IT GIVES US A RICH LIFE.”

On What Maine Offers

Stadler: A lot of people focus on the fact that women are less ego-driven, and I agree with that, but I think there’s also the fact that a lot of us are product-driven. And we live in a state that has better product — as good, if not better, especially the ocean — than any other state. Like, our teeny little state can match the biggest and best markets in the U.S., in season. I think that is a huge part of why [those of us from away] come to Maine. You work with the cheese and you work with all the farmers — everything you work with, it’s just phenomenal. So it’s less about ego and more about serving good dishes.

Kelly: The resources are what drew me, like the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. I had family ties also, but the opportunity as a chef was the products that were here. And it’s only exponentially grown.

Finigan: I feel like anywhere in Maine — out on the islands, Stonington, Deer Isle — it’s a community. All I have to do is stop in the coffee shop and tell whoever, “Hey, I’m looking for this.” Or I’m picking up my farm order and, “Hey, do you know anyone looking for a part-time job?”

French: We love this place, we love the ingredients here, and also, it gives us a rich life. You can be here and have a family and just have a life that’s authentic. It’s hard enough work that at the end of it, to know that you’re doing it on your terms and that it’s something that you love and you’re proud of — I mean, that’s Maine. You can have that quiet, happy, real life.

Charles: It’s a nice place to raise a family, if that’s something you intend to do. It’s a nice place to be out of the city. Having a restaurant in the city is expensive and frenetic and chaotic, and it’s a lot more tranquil here. You have all the same problems, really, but you don’t have that constant, electric craziness.

Kelly: I think it’s more of a family atmosphere. Like in Rockland, everyone knows each other. We’re the only people we see, whether we’re in work or out of work. You go out, you see everyone at the supermarkets, the bars, the restaurants. Wherever you go, you’re going to see everybody you work with and your customers too.

Stadler: One of the things about Portland, and the whole state, is that we are nurturing ourselves. There is a lot of support. I think one of the things that makes the restaurant scene in Maine particularly special is — I just got a message from [another chef], and he’s like, “Can I pick your brain about a dumpling? I won’t share this.” And I’m like, I’m an open book! You can share whatever you want. I’m not trying to hide information about my business. We want people to grow. My success has very much been because of other people’s success. The fact that all ships rise on a high tide — is that the phrase? — I think that very much exists in this state.

Desjarlais: It was 2007 when I came back here to open Bresca. I’d been working all around, and I felt like, I’m going to hang my shingle up, nobody’s going to say anything, I don’t feel any pressure. I’m just going to do what I do, and hopefully, people will come. I didn’t feel like there was a ceiling. Now, I think that’s changed. There’s a community still, yes, but now there’s so much press. It’s nonstop. I feel like there’s a lot more pressure on every new place that opens now, female-run or not, just to get bodies in seats.

Charles: There’s so much competition, and there just aren’t enough people to fill the seats.

Kelly: In the summertime, it’s no problem, but the shoulder seasons . . . .

I feel like 80 percent of the résumés I get are people moving to Maine from other locations to open a restaurant, and they want to work for me for a year or two, then they want to do their own thing. I’m like mmmmm . . . what are you doing here?

French: It’s because we’re living the dream.

Wolfertz: We have a lot of great restaurants in Rockland and Camden, but I feel like, because we’re a smaller market, more is better. Because if they can’t get into one, they can get into one next door, and so they still come.

Kelly: We’re also a tight community. All of our staff goes to her restaurant on their days off, and hers all come to mine on their day off. All of us are friends.

Wolfertz: We love each other.

On What Maine Offers

Stadler: A lot of people focus on the fact that women are less ego-driven, and I agree with that, but I think there’s also the fact that a lot of us are product-driven. And we live in a state that has better product — as good, if not better, especially the ocean — than any other state. Like, our teeny little state can match the biggest and best markets in the U.S., in season. I think that is a huge part of why [those of us from away] come to Maine. You work with the cheese and you work with all the farmers — everything you work with, it’s just phenomenal. So it’s less about ego and more about serving good dishes.

Kelly: The resources are what drew me, like the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. I had family ties also, but the opportunity as a chef was the products that were here. And it’s only exponentially grown.

Finigan: I feel like anywhere in Maine — out on the islands, Stonington, Deer Isle — it’s a community. All I have to do is stop in the coffee shop and tell whoever, “Hey, I’m looking for this.” Or I’m picking up my farm order and, “Hey, do you know anyone looking for a part-time job?”

French: We love this place, we love the ingredients here, and also, it gives us a rich life. You can be here and have a family and just have a life that’s authentic. It’s hard enough work that at the end of it, to know that you’re doing it on your terms and that it’s something that you love and you’re proud of — I mean, that’s Maine. You can have that quiet, happy, real life.

Charles: It’s a nice place to raise a family, if that’s something you intend to do. It’s a nice place to be out of the city. Having a restaurant in the city is expensive and frenetic and chaotic, and it’s a lot more tranquil here. You have all the same problems, really, but you don’t have that constant, electric craziness.

Kelly: I think it’s more of a family atmosphere. Like in Rockland, everyone knows each other. We’re the only people we see, whether we’re in work or out of work. You go out, you see everyone at the supermarkets, the bars, the restaurants. Wherever you go, you’re going to see everybody you work with and your customers too.

Stadler: One of the things about Portland, and the whole state, is that we are nurturing ourselves. There is a lot of support. I think one of the things that makes the restaurant scene in Maine particularly special is — I just got a message from [another chef], and he’s like, “Can I pick your brain about a dumpling? I won’t share this.” And I’m like, I’m an open book! You can share whatever you want. I’m not trying to hide information about my business. We want people to grow. My success has very much been because of other people’s success. The fact that all ships rise on a high tide — is that the phrase? — I think that very much exists in this state.

Desjarlais: It was 2007 when I came back here to open Bresca. I’d been working all around, and I felt like, I’m going to hang my shingle up, nobody’s going to say anything, I don’t feel any pressure. I’m just going to do what I do, and hopefully, people will come. I didn’t feel like there was a ceiling. Now, I think that’s changed. There’s a community still, yes, but now there’s so much press. It’s nonstop. I feel like there’s a lot more pressure on every new place that opens now, female-run or not, just to get bodies in seats.

Charles: There’s so much competition, and there just aren’t enough people to fill the seats.

Kelly: In the summertime, it’s no problem, but the shoulder seasons . . . .

I feel like 80 percent of the résumés I get are people moving to Maine from other locations to open a restaurant, and they want to work for me for a year or two, then they want to do their own thing. I’m like mmmmm . . . what are you doing here?

French: It’s because we’re living the dream.

Wolfertz: We have a lot of great restaurants in Rockland and Camden, but I feel like, because we’re a smaller market, more is better. Because if they can’t get into one, they can get into one next door, and so they still come.

Kelly: We’re also a tight community. All of our staff goes to her restaurant on their days off, and hers all come to mine on their day off. All of us are friends.

Wolfertz: We love each other.