Rachel Schattman has never encountered a crop quite like wild blueberries. “They’re perennial bi-annuals,” says the University of Maine agroecologist and former vegetable farmer. “They’re endemic to the environment. They’re genetically diverse — a single field might have hundreds of genotypes. They have a special nutritional profile. They have a rich history with indigenous tribes. That’s a beautiful thing.”

Wild blueberry research at the University of Maine dates back to at least 1898 and has continually responded to growers’ needs. Schattman is leading a new wild blueberry research project, a rainfall experiment to gauge climate change’s effect on berry quality and yield. She and graduate assistant Ali Bello designed the study after brainstorming with Wyman’s agronomist Bruce Hall. “It’s been a joy to hear about the industry’s very real and grounded needs, and to apply my training and resources to answer their questions,” Schattman says.

The benefits are reciprocal, says Diane Rowland, dean of UMaine’s College of Natural Sciences, Forestry, and Agriculture, and director of the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station. Partnerships with industry leaders like Wyman’s “ensure our work is grounded in what farmers encounter every day.”

Wyman’s is deeply invested in proactively understanding how wild blueberries may respond to climate change. As a further show of its commitment to academic research, the company has partnered with UMaine to establish the Wyman’s Wild Blueberry Research and Innovation Center in the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station on the Orono campus. “As an industry leader in this crop,” Hall says, “it’s rewarding to be partners with smart scientists who call us and say, ‘Hey, I have an idea…’”

Below, three ways Wyman’s blueberry crop is helping facilitate scientific research.

Say “Cheese,” Bees

Without bees there would be no wild blueberries, so Wyman’s supports academic research into pollinator health, including providing seed funding for the Center for Pollinator Research at Penn State University. Wyman’s fields are a lab for Penn State entomologist Christina Grozinger and University of Pittsburgh graduate student Mason Unger, who are developing a precision-agriculture approach to managing and conserving bees. “The challenge to wild blueberry fields is the very natural habitat,” Grozinger says. “There are lots of dips and hills in the topography and in the surrounding habitat. Our question: How do microlandscapes and microclimates influence bee presence and their pollination rates?” To find out, Unger and his grad assistants transect the field daily during pollination season, meticulously identifying and counting bees and recording conditions like sunlight, rainfall, and temperature. Another team is now developing still and video cameras so the bees can be monitored when people aren’t present. “We’re trying to see how precise we can go to get an idea of where it’s most beneficial to place bee colonies and how to manage plants so bees come to them.”

Future Farming

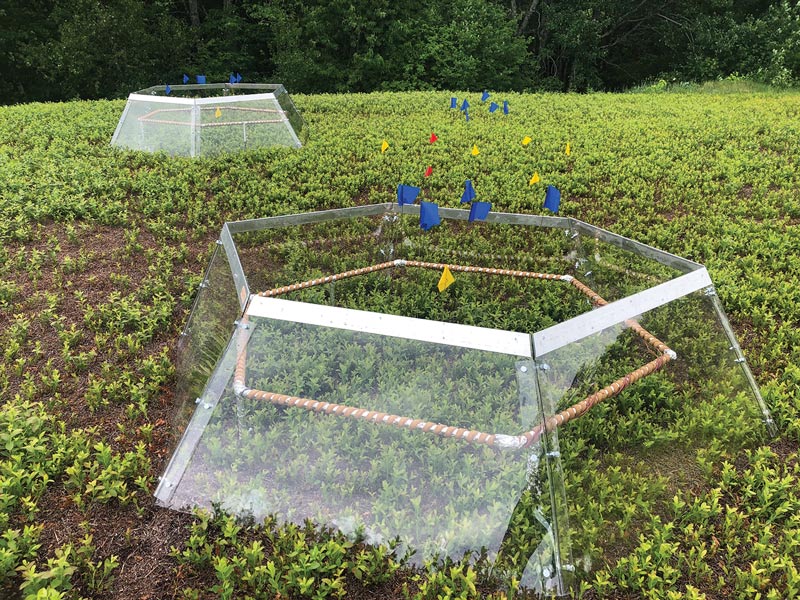

Down East Maine’s starkly beautiful wild blueberry barrens have been looking even more otherworldly of late. Two dozen domes resembling small spacecraft have arisen in Wyman’s fields and at UMaine’s research farm in Jonesboro. Designed by UMaine School of Biology and Ecology professor YongJiang “John” Zhang and doctoral candidate Rafa Tasnim, the six-sided, clear-plexiglass structures have a decidedly earthly mission: to mimic the global warming predicted over the next several decades. Each climate chamber creates an environment that’s 3 to 9 degrees above ambient temperature, depending on whether it’s passively heated (like a greenhouse) or outfitted with heat tape (the same sticky cables Mainers use to prevent frozen pipes). “We’re not just studying the problems,” Zhang says. “We’re testing techniques to mitigate them.” The good news: it appears that a longer growing season will yield more and bigger berries. The bad news: prolonged droughts and dryer soils will stress plants — but researchers are already on it, testing ways to deliver nutrients and moisture to wild blueberries in a warmer world.

Waste Not

Can lumber waste help Maine growers yield robust wild blueberry crops? For nearly 2,000 years, farmers have used biochar, a carbon-rich charcoal derived from the thermal decomposition of sawdust, bark, and other wood and agricultural byproducts, to retain water and fertilizer in soils. Today, scientists are touting biochar’s ability to absorb carbon emissions from the atmosphere — and potentially mitigate climate change. At UMaine’s School of Forest Resources, professor Ling Li and grad student Abby Novak hope to get an added benefit from biochar. In collaboration with Hall and Zhang, they’re testing fertilizer-infused biochar mulches to deliver nutrients directly to plants. “Wild blueberry soils are sandy, which is not good for holding water, but water is important for yield,” Zhang says. “Biochar’s ability to increase water retention is really significant.” Still in its infancy, this project is shooting for a hat trick: less wood in the waste stream, bountiful wild blueberries, and a healthier atmosphere.