By Will Grunewald

From our May 2022 issue

Novelist Deborah Joy Corey has resided in the fishing town of Castine — population 1,300 — for more than a quarter century. Still, she was caught off guard several years ago when she started looking into the matter of hunger, talking with the people who run food pantries, homeless shelters, and other community groups in the area, and she began to realize the scope of the problem in her own backyard. “I was shocked,” she recalls. “In my own county, Hancock County, so many children go without enough food.” She was struck by the lack of fresh products available through food banks, and that, she figured, was a matter she could impact.

In 2019, Corey founded the nonprofit Blue Angel. First, she recruited local farmers, home gardeners, restaurants, and markets to donate food, and she started a flagship garden for the organization on the grounds of Castine’s Episcopal church. Presently, Blue Angel can help to feed up to 30 families at a time, delivering weekly supplies straight to their doors. When the group has a surplus, it donates to nearby food banks, and in the summer, at a shelter in Orland, it stocks a free vegetable stand. “We’re primarily serving the working poor,” Corey notes, “many of whom are already working multiple jobs.”

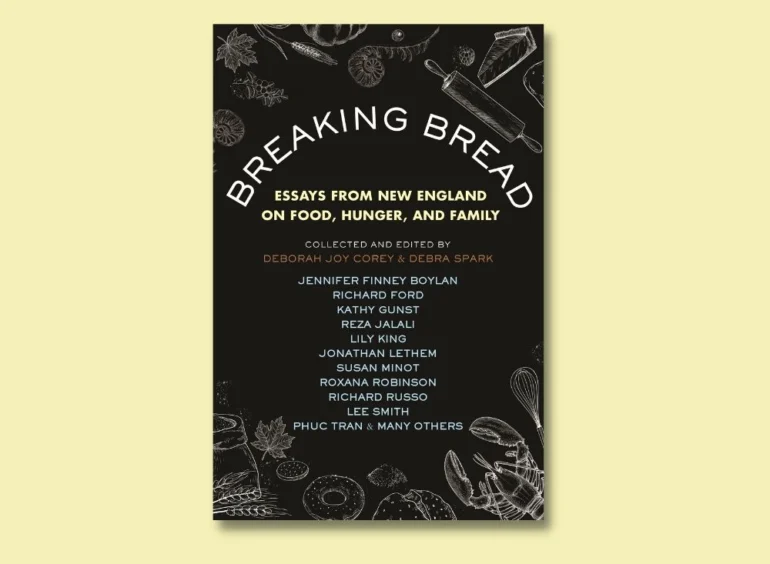

Instinctively, Corey viewed the matter of hunger through a writerly lens. In particular, she thought about her own happy memories of food relative to the stress and anxiety around food felt by others in her community. “We all have food stories,” she says. “We all have a relationship to food, and it’s so varied for everyone.” And so she had the idea for a collection of food essays from many points of view, proceeds from which would fund Blue Angel. As the scope of the project grew, she teamed up with her friend and fellow novelist Debra Spark, a creative-writing professor at Colby College. Together, they recruited writers and edited what has become Breaking Bread: Essays from New England on Food, Hunger, and Family, out this month from the nonprofit Beacon Press. In all, nearly 70 authors pitched in. Many of them are national figures (some with Pulitzers to their names), others are well-known in these parts, and still others are relative up-and-comers. All of them contributed for free. “For these writers, it’s their way of giving,” Corey says.

Among the literary types, there’s Richard Russo reminiscing about beans — from Portland’s B&M baked beans in childhood to pasta fagioli from Venice as an adult. Ron Currie plumbs the shame he feels at the shame he felt when his mother took a job at his junior-high cafeteria. Lily King reflects bittersweetly on a lifetime of baking chocolate-chip cookies. Among food specialists is NPR’s Here and Now cooking guru Kathy Gunst, detailing her love affair with pickles. Portland Press Herald food editor Peggy Grodinsky recalls a lifelong ritual of making pancakes, dating to the heyday of fake maple syrup. And elsewhere throughout the book, Portland Immigrant Welcome Center executive director Reza Jalali remembers his mother’s kofta back in Iran. Tattoo artist and high-school Latin teacher Phuc Tran considers pizza then and now, from his immigrant mother’s combination of white bread, ketchup, and American cheese to the Italian-style margherita he forces upon his Domino’s-loving daughters.

The pieces run the gamut from sad to sweet. Food stories are simply another way of telling life stories. For their parts, Spark writes about hunting for Europe’s chocolate Kinder Eggs in Maine, while Corey contemplates her family’s intergenerational love affair with cooking. It becomes quite clear how Corey could come to worry over what other families are doing for dinner too. “My mother used to tell me you had to pick a place and stay there,” she says. “I didn’t necessarily recognize it at the time, but there was a lot of wisdom in that. In your community, that’s where you can do the most good.”