Interview by Sarah Stebbins

From our July 2025 issue

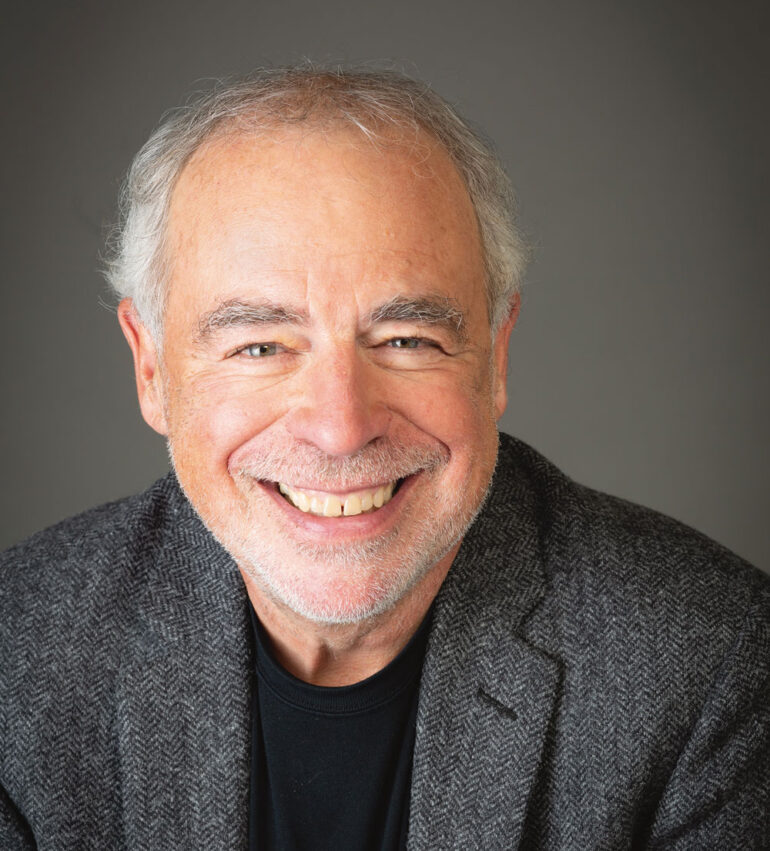

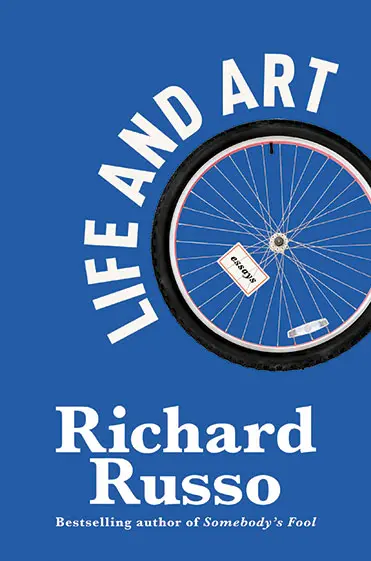

A few years ago, Portland author Richard Russo returned to the street he grew up on in the former mill town of Gloversville, New York, and found it decimated. As he describes in the essay “Ghosts,” in his new anthology Life and Art (Knopf; hardcover; $28), many of the modest, one- and two-family dwellings his factory-worker grandfather and neighbors took great pride in maintaining are crumbling or abandoned, and the once-bustling block is all but deserted. “That essay absolutely wrecked me to write,” Russo says. “Remembering what those houses meant to those men, most of whom had never owned a house before.”

Russo has wrestled with issues of place and class in 10 novels, a memoir, two short-story collections, and now, two books of essays. Most of his novels, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Empire Falls, about a fictional Maine mill town, are set in spots like Gloversville. His latest work offers a profoundly personal take on the societal tensions he has been grappling with for decades. “I don’t think I’ve gotten to the bottom of any of it,” Russo says. “And that’s the good news because, as an artist, what you want is a subject you’ll never figure out.”

How did this essay collection come about?

A lot of the essays were written during the pandemic, when I wrote much more nonfiction than I typically do. Normally, I divide my time between writing novels, writing short stories, and writing for the screen. Yet, at some point, I thought what I really needed to do was write an essay about disruption through the eyes of the movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Why? I really don’t know, but the need revealed itself with a kind of urgency. One thing the pandemic did was make us very aware of our mortality. And the older you get, the more necessary it seems to be to look to the past and try to make sense of things.

Were there any big revelations?

Essays like “Marriage Story” really forced me to understand the gift I have been given in terms of having parents who had come to radically different conclusions about America. My father, the decorated World War II hero, did not believe, as my mother did, that at the end of the war all the doors that had been closed to people like them were suddenly going to be thrown open. My mother saw me as vindication that she was right. But my father, who did road construction, understood that while America certainly worked for people like me, it was not committed to people like him. What I came to terms with in the book is that this is the greatest gift for an artist, a problem that has no solution, a conflict you can return to again and again, in novel after novel.

How does that play out in your work?

With every novel I’ve written, I’ve realized about halfway through that there’s something I couldn’t get at because of the way I’ve chosen to tell the story. The Risk Pool is a father-and-son story told through the eyes of the son. So the next book, Nobody’s Fool, is a father-and-son story told through the eyes of the father. But the point of view is omniscient and I realized there’s something else I wanted to tell about this place and these people through a third person, so Everybody’s Fool was born. What keeps you coming back is the knowledge that you’ll never figure this out.

What appeals to you about the essay format?

It allows me to look at issues more directly and use a soapbox I wouldn’t dream of using in my novels. In an essay like “The Lives of Others,” I’m able to talk about cultural appropriation and people who say artists shouldn’t write about things with which they have little firsthand experience. I think if you were to take that advice, you might as well hang it up. I talk about one of my favorite characters, Sister Ursula, from the short story “The Whore’s Child.” You couldn’t find someone with less to go on than me writing about an octogenarian Belgian nun. And yet, I don’t think I’ve ever created a character I felt more attuned to. If you have that deep emotional connection with a character and you match it with the humility art requires, you will find out something about her that you didn’t know. And, more importantly, you will find out something about yourself that you didn’t know.