By Virginia M. Wright

From our June 2020 issue

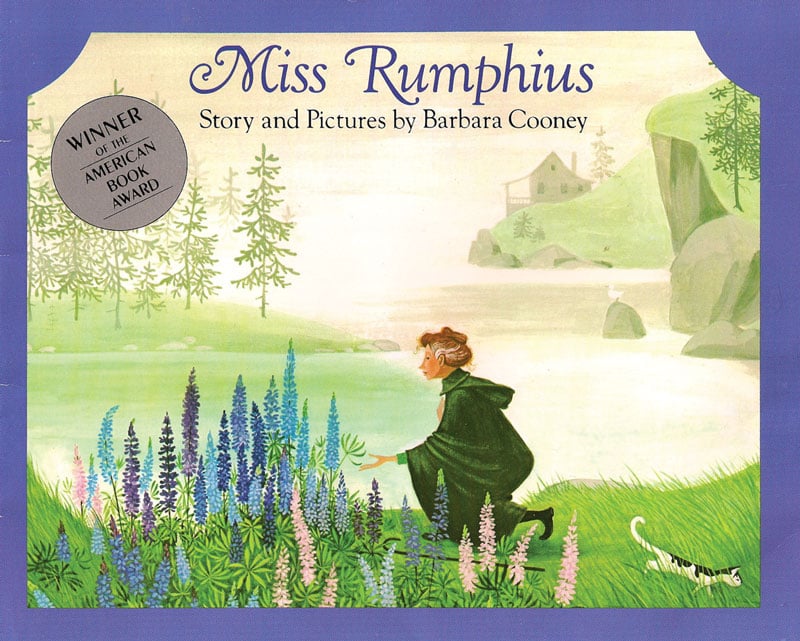

What we remember are the lupines, but if Miss Rumphius were just a sweet origin story about the blue, pink, and purple blooms blanketing Maine roadsides in spring, we probably wouldn’t be thinking about it at all, 38 years after it was written.

Barbara Cooney didn’t care for sugary tales. “It does not hurt [children] to read about good and evil, love and hate, life and death,” the author and illustrator said in her 1959 Caldecott Award acceptance speech. “Nor do I think they should read only about things that they understand. … A man’s reach should exceed his grasp. So should a child’s. I will never talk down to — or draw down to — children.”

And so, in the story narrated by her great-niece, Alice Rumphius is an unconventional heroine. She travels alone to faraway places. She never marries or has children. She grows old, and for a time, she’s bedridden in her house by the sea. Neighbors label her “That Crazy Old Lady” when, to fulfill her childhood promise to “do something to make the world more beautiful,” she scatters lupine seeds as she walks over fields and headlands near her home.

Cooney doesn’t explain Miss Rumphius’s solitary life, nor does she pass judgment on how people see her. Her softly colored folk-art illustrations reveal what isn’t explicitly written: We know the townspeople come to love Miss Rumphius’s eccentric pastime because we see them gathering lupine bouquets. We know Miss Rumphius’s home is on the Maine coast because the rugged landscape and cottage architecture could be nowhere else.

Cooney called Miss Rumphius (1982) and Island Boy (1988) her “hymns to Maine.” Of the more than 100 books she wrote and illustrated, she said those two, along with Hattie and the Wild Waves (1990), “are as near as I ever will come to an autobiography.”

Her love for Maine was lifelong, though she didn’t move here until she was 64. The daughter of a stockbroker and a painter, she grew up on Long Island and summered in Maine as a young girl. She married twice and raised her four children in Massachusetts. When she was in her 40s, she embarked on travels that opened her eyes to sense of place. She settled in Damariscotta in 1983, the year Miss Rumphius won a National Book Award.

Maine returned her embrace. In 1996, then-Governor Angus King declared Cooney a “living treasure of the state of Maine” and designated December 12 Barbara Cooney Day. “I consider Miss Rumphius one of the best five children’s books ever written,” King, a father of five, said.

Only at the end of Miss Rumphius, when she promises her great aunt that she too will do something to make the world more beautiful, do we learn the young narrator’s name: Alice. In her spare style, without a shred of didacticism, Cooney gives us a story of living with intention, of seasons, and of the circle of life.