At the beginning of Catherine Armsden’s debut novel, Gina Gilbert and her sister, Cassie, sort through things in the attic of their childhood home one week after their elderly parents have been killed in a car crash. Cassie laments that Gina no longer has a reason to come east. “What’re you saying?” Gina responds. “You’ve always griped about coming to Maine. And anyway, we were miserable here. Admit it. You’re as finished with the house as I am.”

But Gina, an architect, is nowhere near finished with the house. It triggers emotions so intense that they follow her home to California, infecting her relationships with her husband and children and impinging on her ability to respond to a wealthy client’s desire for a luxury house. Unsettled and anxious, Gina returns to her hometown, fictional Whit’s Point in southern coastal Maine, to reckon with the family history that has been exhumed by the house’s pending sale.

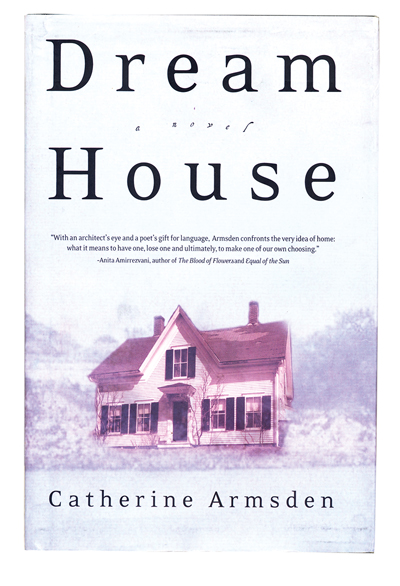

Like her main character, Armsden is a Maine native now practicing architecture in San Francisco. In this contemplative novel, she investigates the complex nature of houses — how they can embody happiness and warmth or how, tomblike, they conceal secrets whose invisible poison seeps into the generations who live within.

Gina is haunted by two houses in Whit’s Point: the architecturally unremarkable and slightly neglected rental that she and Cassie grew up in, and Lily House, an 18th-century landmark built for a famous ancestor (he was George Washington’s private secretary) and a perpetual source of resentment for Gina’s mentally unstable mother, Eleanor, whose sister inherited it. Lily House also comes with a mystery: family lore holds that somewhere within its nooks and crannies hides a priceless trove of the first president’s letters.

Armsden investigates the complex nature of houses — how they can embody happiness and warmth or how they conceal secrets.

Dream House is not a page-turner. There’s only a sliver of suspense: the whereabouts of the Washington letters pop up frequently in Gina and Cassie’s reminiscences, but they’re not the motivation for Gina’s Maine sabbatical. Instead, Dream House is more of an amble over a terrain that many readers will recognize: Gina is an ordinary woman experiencing an ordinary midlife crisis around a commonplace event — letting go of a childhood home. The story lacks heft, but its familiarity is engaging.

Drifting between the present day and Gina’s childhood, Armsden’s narrative pokes and twists at conventional notions of home: Lily House is now a museum, its rooms secured by velvet ropes — even the live-in caretakers who dust the antiques daily are not allowed to lounge inside them. Meanwhile, the house that Gina’s family never owned — a place they scurried to tidy whenever the landlord stopped by — overflows with powerful memories, bitter at first, but sweetened ever so slightly as Eleanor’s character comes into sharper focus, revealing her strength, independence, and even capacity for joy.

Armsden’s domestic explorations don’t extend to place and culture. She describes Whit’s Point, which is modeled after Kittery, with the ease and authenticity of the Maine native that she is, but the town serves largely as backdrop and has little influence on plot and character. Her domain is interiors, both physical and psychological.