By Lois Lowry

From our November 1977 issue

The kid grew up in Maine, in the kind of town that didn’t have its picture on a postcard. He grew up in the kind of house that had a heritage of For Rent signs and Sears Special-This-Week paint daubed over deep flaws. There was the memory of a father who had fled when the boy was very small, and the tired and determined presence of a mother who worked in a bakery, in a laundry, in whatever there was, to keep two little boys clothed and fed. There was an outhouse, painted blue, and a well that sometimes went dry, so that they had to carry water from a distant spring.

He called his mother Ma. She brought him broken cookies from the bakery where she worked at night while he was sleeping; and she told him, with a fervor that came from a combination of resolute fundamentalism and the staunch New England belief that grit and stubbornness bear fruit like apple trees in rocky soil, that he would someday be a success.

To his mother, success meant that he would go to college, find a steady job, marry, own his own home, that it would have indoor plumbing and paid-for furniture, and that his own children would never be cold, hungry, or ridiculed.

And the kid believed her. He believed her even though he was the kind of kid who seemed to have two left feet, both with their shoelaces untied. The one chosen last for teams, he was the kid who’d never had a trip to Disneyland, the one who didn’t have a brand-new set of clothes on the first day of school.

What he did have was an introspective and perceptive mind, a mind that from early childhood had been cataloging the nuances of life in a small, unsophisticated town. Durham, Maine, was a town where a young boy knew everyone: the gas-station attendants, garbage collectors, spinsters, drunks, farmers, local eccentrics, and mongrel dogs. He saw and filed away in his brain all their frustrations, their fears, their hopes, and the ways they faced both life and death.

Later as a young man, he began to write those things down. And to the things he wrote, he added the things that had been working in his own abundant imagination, nourished there by his reading that had encompassed Superman, Salinger, Shelley, and Shakespeare. He mixed the Maine town with magic, mixed creatures with long, curved teeth and nocturnal secrets into the prosaic populace of his boyhood, mixed the dreams and disguises he had sensed and guessed at with metaphors of stalking evil at war with the intrepid forces of good.

He was still a kid, really — 25 — when success came. Young enough to take a kid’s delight in thumbing his nose at the past, at the guys who had laughed when he showed up in too-short jeans to try out for the ball team. Young enough to call up his mother and say, “Guess what, Ma?” as if it were a sixth-grade report card with all As.

But old enough to know that when the headlines said “Stephen King is a success,” it didn’t mean life was going to be easy. Not any easier than it had been to lug water over the field from the spring. Just different, and more fun, most of the time.

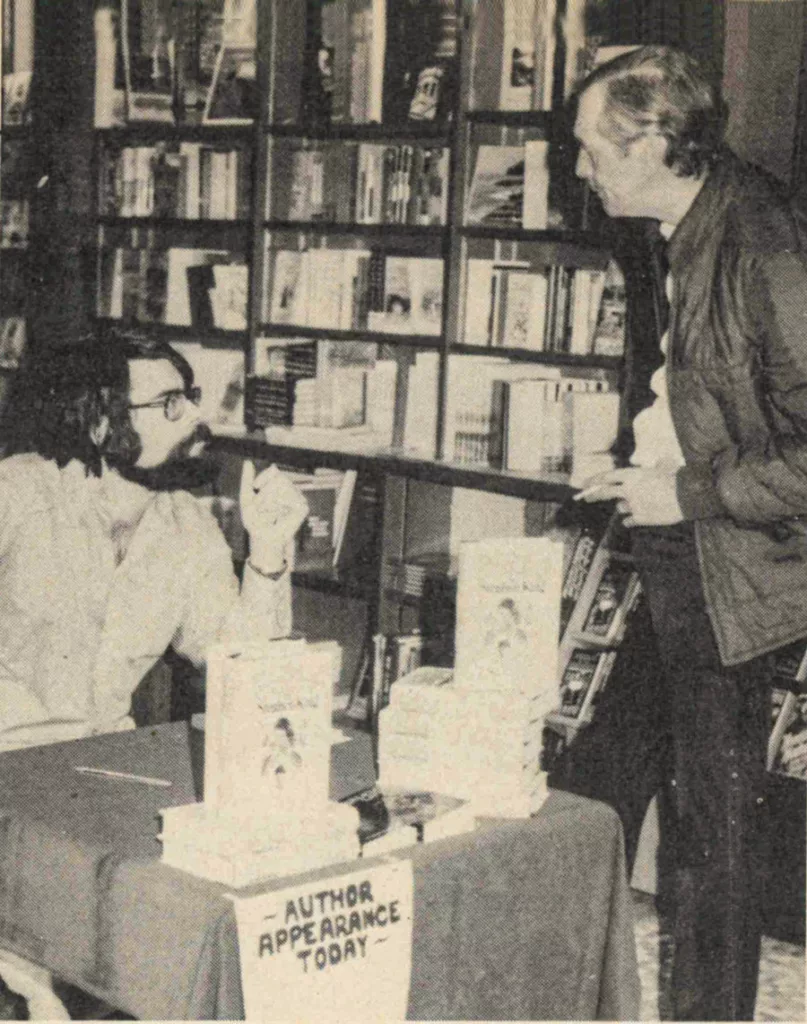

“So you’re Stephen King?” asks the man in the double-knit suit as he presents his book to be autographed. “I thought you’d have three heads.”

“Nope,” grins the young author, as he signs his name with a flourish on the inside cover of The Shining, “only one. It all comes out of one head.”

King is sitting in the front section of a Maine bookstore for the autographing session, surrounded by copies of his best sellers: Carrie, ’Salem’s Lot, and The Shining. The books are balanced in stacks, their covers familiar now to the public. There isn’t a chiller-lover anywhere in the country who doesn’t recognize the blood-drenched, shrieking face of Carrie, or that single ominous scarlet drop that decorates the all-black cover of ’Salem’s Lot.

Maine natives are not effusive people; nor are they likely to look kindly on a blue-jeaned upstart who has written of their home territory in allegories heavy with evil and permeated with the violent, bizarre, and occult. Nevertheless, they come, clutching their books, to get a glimpse and the signature of the man who has prodded at the perimeters of their lives with his perceptions and his pen.

“You’re super,” say the young, handing over their dog-eared paperbacks for the autograph.

“You’re crazy,” say others, belligerently holding out their books for the talismanic signature.

“There’s almost always one old lady at an autographing session,” says King, looking over his shoulder as if she might be waiting behind him today, “who comes and says, ‘You’re writing godless things, young man.’ I just humor her along, and hope she doesn’t have a sharpened nail file.”

Sharpened nail file. King always speaks in quick, facile allusions and unexpected bursts of metaphor. Now, his eyebrows come together for a second at the midpoint of his dark-rimmed glasses, and you can feel him tucking the thought of a sharpened nail file away in his mind for future use. Beginning with “s,” it would go into the mental catalog somewhere between the throbbingly cryptic refrain, REDRUM, that represents supernatural evil in The Shining, and telekinesis, the diabolical force in Carrie.

Steve King looks up, smiles, and the hard, shiny glints of fictional weaponry are all out of sight, submerged, indexed in the brain until he calls them forth next at the typewriter. His is the easy, open, self-confident smile of a young man who knows his craft well and doesn’t wear it like a costume. No malevolent, spooky, sidelong glances from Stephen King, despite the magazine photographer who once caught him in reflected light so that his eyes were obscured and he appeared to be directing hostile psychic beams at the reading public. That was part of the price he pays for the successful writing of horror fiction. That, and the practical jokes, like the journalist who arrived for an interview wearing plastic vampire fangs.

It’s a strange, unsettling kind of success. Perhaps not the kind his mother, now dead, wished for him, mingled as it is now with so much money that he no longer knows what he has earned; entangled now with the complicated concerns of public appearances, television interviews, promotion tours, autographs, accountants, agents, and the ubiquitous IRS.

Sitting, dungareed and chain-smoking, in his Cadillac, King hums along, slightly off-key, to a country-and-western station on his radio. “Buy a little house,” the nasal radio voice sings. “Plant a little garden. Eat a bowl of peaches.” Steve King knows all the words. The house in the country, the family, the garden, were the things he wanted. And to write. He had them; he has them still. But on Saturday, he has to be in North Carolina to appear at the premiere of a movie made from one of his books. Then, he must go to New York and have lunch with a publisher. Or was it a producer? The push-button windows on the Cadillac aren’t working properly. He’s smoking too much, taking too many Bufferin. He’s just 30 years old.

Country life suits Stephen King. He looks at home in Bridgton, Maine. To meet him there, in a spacious, toy-strewn house filled with the high voices of children and the sunshine that reflects brilliantly from Long Lake, it is hard to believe that murderous creatures are brewing in his brain like newts in a cauldron. It’s a placid, unostentatious kind of country living that reveals nothing of the lurking horrors of the mind that made it possible.

It’s a hard house to find. A visitor must know the landmarks, the right turn to make in the narrow, winding road that runs along the lake. Metaphorically speaking, the journey to the Bridgton house has not been an easy one, either.

When he was still an undergraduate scholarship student at the University of Maine, King began selling short fiction. He sold to magazines with titles heavy on machismo and their back pages filled with ads that he hoped his mother wouldn’t see. But those things don’t matter much to a would-be writer; what matters is the letter that says, “We are accepting . . .”; what also matters is the check that accompanies it. They weren’t sales that would support an expanding family. Steve had married Tabitha before she finished college. They were living in a cheap apartment, and he worked in a commercial laundry, writing at night when the first baby wasn’t crying. Fate, in its mysterious way, moved into the laundry where he worked, in the form of a slightly loony lady carrying a bag of dirty clothes. What was she like, he wondered, under that bizarre facade of rigid femininity. Why was she spouting Biblical quotations as she folded towels? What kind of children would she have?

The child he envisioned was the adolescent Carrie White, who has now affected countless young people across the country with her combination of fragile vulnerability and violent, unexplainable powers. He wrote a few pages of Carrie. Hated them, crumpled and threw them away.

His wife, Tabby, emptied the wastebasket. Uncrumpled Carrie. And said, “Steve. Hey. Go on with this.”

Three years ago, the paperback rights to Carrie sold for almost half a million dollars. It was dedicated to Tabby. When Doubleday accepted Carrie in 1973, Steve King realized for the first time, as he puts it, “that I wouldn’t have to work for a living anymore.”

So writing isn’t work? Writing successful novels is as gut-wrenching as heavy lifting, and no one knows it better than this young man who has turned out three best sellers in as many years and who has the flattened, strewn Bufferin boxes and cigarette packs on the floor of his Cadillac to show for it. It’s an ambivalent kind of success. The money surges in; book clubs compete for the next novel; one film is nominated for an Oscar, and Stanley Kubrick has bought the rights for another. A review from the Midwest is lavish with praise; a pinched-mouth review from New York gives its verdict: “Clichés.” Smile. Wince. Reach for a cigarette.

An aspirin. Turn on some country music and hum. Tease Tabby. Scold little Joe for riding his plastic Batmobile around the living room too noisily. Stroke the yellow cat named Carrie. Diaper the new baby who smiles in the sunny bedroom. Downstairs, the typewriter waits. The terrors and spooks and nameless, faceless creatures are all down there in the study, waiting to be written. And the public waits, the critics wait, to see if he can do it again.

Do what? Jump out and say “Boo” at them. That’s how King described it. That’s what the public wants, what they’ve wanted ever since Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818, since Bram Stoker came up with Dracula in 1897. Since long before either of those.

Shelley and Stoker wrote successful horror. So does King. But what is it that distinguishes “good” horror from the old Tales from the Crypt that you read with a kind of gleeful fear when you were a kid?

It seems to lie in the realm of possible veracity, of metaphor, of the well-crafted unspoken. When you were nine years old, with wide eyes and your tongue tucked between your teeth, you could curl up on the front porch and read about oozing purple creatures who emerged from graveyards at night. It scared the wits out of you, while you were reading it; but when you put it down, you could laugh, and go in and eat supper, and the purple creatures stayed in the comic-book pages where they lived. Because you knew they weren’t real, even at nine.

You can raise an urbane eyebrow when you read ’Salem’s Lot because the vampires King has created in the book aren’t real either. You know that, and King knew it when he dreamed them up. But what they represent is real. That’s why, even when the eyebrow is raised, the forehead remains furrowed. Good and evil do exist uneasily side by side in small New England towns, in towns and cities everywhere, and sometimes it’s impossible to tell them apart. In ’Salem’s Lot, it is very hard to separate the vampires from those who have not been tainted; that’s why, when you put the book down, you don’t laugh and put it out of your mind.

Similarly, in The Shining, King’s most ambitious work thus far, the horror does not lie solely in the supernatural power of a very small boy who can call into being both the past and the future. It lies in the more real, complex problems with which King has intertwined the metaphor of the occult: the specter of alcoholism, which haunts the book’s characters; and of child abuse, which is far more frightening than monsters.

It is King’s talent for combining the real and the imaginary, in a way that makes the imaginary seem possible, that has made him a millionaire at 30. He’s a little embarrassed by it, tries to explain it, speaks articulately and with introspection about it.

“People are always asking me if I’m strange, writing about stuff like this,” Steve says. “But I don’t think a taste for horror is strange at all.

“When you’re a kid, your appetite is for things like Grimm’s Fairy Tales. You know what happens to the Little Tin Soldier? He melts at the end. Alright, that’s allegory. But kids don’t look at it that way. All they see is that guy melting.

“People grow up, and their need for fantasy remains. You’re made a child again, through fear, and that’s a normal desire.”

“Carrie, for example, lives out a nightmare that all teenagers go through. Not being accepted by peers. And all high-school kids are full of suppressed violence. Remember how you used to

go home and throw your books across a room if you’d flunked a quiz? Carrie lets people relive that violent urge of adolescence.” (In Carrie, his first published book, the teenaged heroine — or antiheroine — destroys not only all the high-school classmates who victimized her, but the entire town as well, with her terrifying telekinetic powers.)

“And ’Salem’s Lot. It’s simply a fairy tale for adults.” (By the conclusion of ’Salem’s Lot, his second book, only two characters, a man and a young boy, remain alive, though not unscathed by the fearsome wrath of the netherworld that creeps out at night in a rural Maine town.)

“You know what I am, really? All I am is the phosphorescent ghost at the funhouse. I’m the guy who jumps out and yells ‘Boo!’”

So Stephen King jumps out again and again and yells “Boo!” a little better each time, to a public that clutches its collective stomach, gasps, and draws the curtains tightly closed before curling up with his newest book. It makes him feel justifiably competent, in control of his craft. It gives him the means to live the way he always wanted to: a quiet life, sharing a closeness to the land with his wife, and to raise their three children with honor, intelligence, and a love of language.

King appreciates his fans, answers the letters they write him, and carries in his wallet a photograph of a young girl from the Southwest because she sent a note that touched him. But he’s had his phone number changed, and the local operator tells countless people every day, “No, I’m sorry, we are not permitted to disclose that number,” because strangers call from all parts of the country to ask for money, interviews, help in finding a publisher for the 800-page novel they’ve written about werewolves, or advice on how to do away with the demonic neighbor who has caused their vegetables to succumb to root rot.

Sometimes, he opens his eyes wide behind the horn-rimmed glasses and realizes that Tabby is at home on the edge of the lake with the kids, listening to music, and he is on a plane to a town whose name he has temporarily forgotten, to sign his name for people he’s never met, and to be interviewed for a magazine that will make him sound glamorous and oracular and start the stream of phone calls and unwanted guests all over again.

So now the house on the Bridgton lake, the house where six-year-old Naomi King has crayoned “Love” on the living-room wall, is for sale. Next year, in a different house, on a different Maine lake, Steve King will sit at his typewriter again. This winter, he, Tabby, and their children will live in England, where the filming of The Shining, starring Jack Nicholson, will be done. From England, he’ll be watching to see if his new book will climb, like the first three, to the prestigious bestseller list of the New York Times and pronounce him, once again, a success.

King sighs, lights another cigarette, promises himself yet again that he will quit smoking, and wonders about the whole thing. Wonders if, when he reached for the gold ring and grasped it firmly, he should have thought a little more about whether he wanted to ride a nonstop merry-go-round.

But the calliope plays and it sounds pretty good, makes you feel exuberant so that you don’t notice the stomachache, and the horses go smoothly up and down, and when you were a kid you always dreamed of riding the biggest one, the white one, and not falling off, ever. So you hang on tight as the world revolves in blurry circles, and you yell, “Hey! Lookit me! I’m the King!” And you love

it — at least most of the time.