By Will Grunewald

From our November 2022 issue

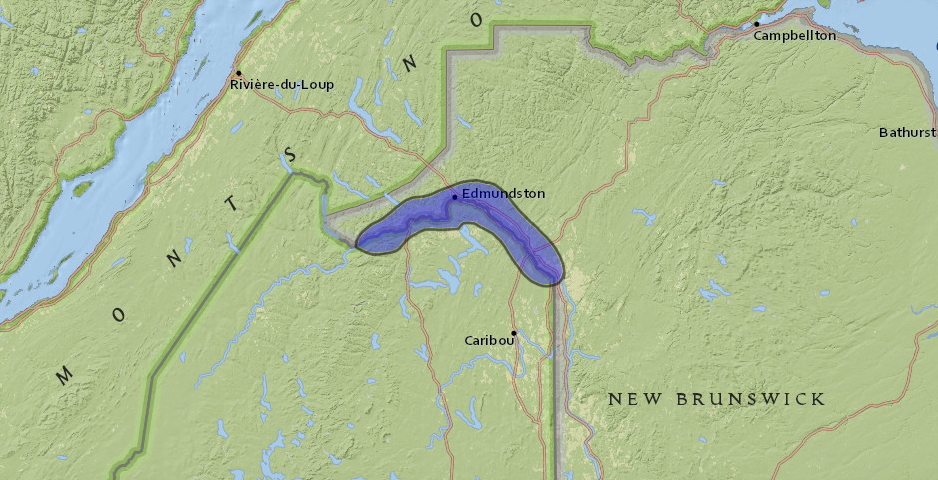

One unverifiable story has it that, before the international boundary was settled, a man from the St. John Valley grew tired of being asked whether he lived in the U.S. or Canada and one time answered, with Roman conviction, “I am a citizen of the Republic of Madawaska!” In another story — a verifiable one — a natural-born rabble-rouser from Maine, John Baker, settled north of the St. John River and, hopeful that the U.S. would someday annex the area, decided to declare an independent Republic of Madawaska in the meantime. The plot fizzled after New Brunswick authorities arrested him, but the notion has lived on that those who dwell along the St. John are a united people. “For a long time,” current president of the Republic of Madawaska Eric Marquis says, “that river was simply a river, not a border.”

The imaginary republic over which Marquis presides spans both sides of the St. John across the top of Maine. He assumed the honorary head-of-state role last year, after being elected mayor of Edmundston, the Canadian city across from the Maine town of Madawaska. Edmundston’s mayor has held the additional title of president of the republic since the mid-20th century, when there was renewed interest in the Republic of Madawaska as a symbolic assertion of identity. Its flag flies about Edmundston’s city hall: an eagle surrounded by six stars, for the Maliseet, Acadian, French Canadian, English, Scottish, and Irish who have called the St. John Valley home.

Today, distinctive elements of the culture range from fiddling technique to forest economies to the locally accented French language to ployes, griddled buckwheat flatbreads traditionally schmeared with pork pâté. Marquis, who’s 47, was born and raised in Edmundston, where most people still parle français. In Maine, French has faded over the years, although “you still have a lot of people who don’t necessarily talk in French every day but can understand it and have a discussion with us,” Marquis says.

People transit back and forth across the border constantly. Families are spread across it. Someone might live on one side but work on the other (Twin Rivers Paper is a big employer — a mill in Edmundston produces pulp and pumps it through a pipeline to Madawaska, where another mill makes paper). Local fire departments have long come to each other’s aid. Edmundston’s nearby ski hill draws Americans, while Madawaska’s drive-in theater draws Canadians. Edmundston’s junior hockey team, the Blizzards, has avid fans across the border, and the same goes for the Madawaska High School football squad — until the pandemic, high schoolers from Edmundston would play for the team. “That really brought the two communities together,” Marquis says, “watching our Canadian and American kids trying to win those games all together.”

Madawaska’s annual Acadian Festival, a celebration of regional culture, draws an international crowd, as did Edmundston’s long-running Foire Brayonne, unrevived since 2020, at which the president of the republic annually made a speech celebrating the local identity. The presidency, Marquis thinks, is a sort of cultural ambassadorship — an opportunity to share what makes the St. John Valley a place unto itself. “When you look at the border from coast to coast,” he says, “having these communities here that have been so close for so long makes us something that is really unique.”