By Peter Andrey Smith

The neoclassical face of the Time and Temperature Building rises 146 feet over downtown Portland’s Monument Square. Through the building’s entry on Congress Street and past the empty storefronts of a former shopping gallery is the elevator, which ascends as high as the 14th floor. After that, it’s a short walk up narrow stairs into a squat rooftop penthouse with few windows.

On a recent overcast day, the building manager pushed open the door and stepped onto the flat black roof, which has no guardrails. Giant antennas perched at the edge, and a familiar sight rested atop the penthouse. It flashed a series of short messages:

10:13

49 º

The tri-panel Time and Temperature sign arrived in 1964, crowning a 40-year-old edifice previously known as the Chapman Building. It quickly became a defining feature of Portland’s skyline. The original sign was built by the American Sign and Indicator Corporation, of Spokane, Washington, a specialist in blinking displays. In the 1970s, the building’s owner, Portland Savings Bank, held contests awarding $500 to whomever correctly guessed the first summer day that the sign would blink out 90 º. Service announcements appeared often, such as YELO BAN when winter parking rules were in effect.

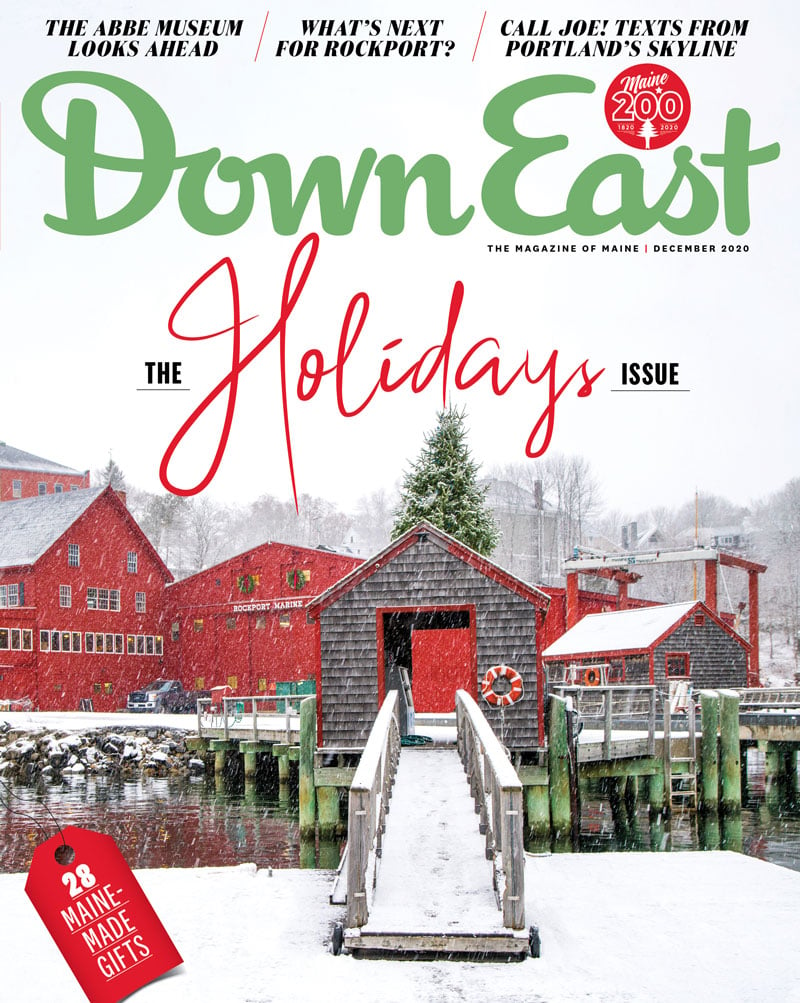

BUY LOCL: The ground floor of the Time and Temperature Building was once home to the Civic Arcade, the first indoor shopping plaza in Maine. The plaza connected to a large, ornate theater that hosted vaudeville acts and screened movies. In the 1960s, the theater was demolished and replaced by a parking garage. Photographed by Corey Templeton.

In 1991, though, a new owner threatened to stop paying the $20,000-per-year electricity bill. Downtown businesses rallied, saying they’d come to rely on the sign for the time and community news. The Save Our Sign campaign wanted to fund the sign by selling advertising, but the 1977 Maine Traveler Information Services Act had banned billboards and other off-premise advertising, including big light-up signs visible from the interstate. State legislators responded by passing a narrowly defined exemption for electronic signs that give the time and temperature.

For six weeks in 1999, the sign went dark so that it could be replaced. Neokraft, a Lewiston company, constructed the new one. The steel frame weighed about six tons, and a helicopter hoisted it into place. The message upon lighting up again:

I AM

BACK

Each side contains 182 bulbs capable of forming four alphanumeric characters. The two-word messages that alternate with the time and temperature are sent in remotely using software developed in the ’90s (before cell phone text-messaging popularized communication through abbreviation). In 2004, the sign mistakenly broadcast 154 º, owing to a faulty transmitter. About once a month, facility manager David Pezzone heads out to the rooftop to maintain the sign. It’s difficult to tell which bulbs have burned out from inside it, so his crew takes notes from afar, penciling in ovals on a card that looks like a Scantron test. Two sides retain the classic incandescent bulbs, Pezzone says, but the side facing I-295 and Back Cove has been outfitted with LEDs.

An official log of every message does not seem to exist. The sign has promoted local organizations: FOOD COOP for the Portland Food Co-op or BUYA BALE for the Maine State Society for the Protection of Animals. It has served as a sort of newsfeed: SOX WIN or GO PATS. Perhaps the most common display of the past ten years has been CALL JOE, referring to the Law Offices of Joe Bornstein, the sign’s current lessee. Since 2010, the firm, which isn’t located in the building, has run messages from over 300 nonprofits. Sometimes, the meaning is obscure: NICE WORK or PINK TUTU.

Earlier this year, after the COVID-19 pandemic started, the sign flashed WEAR MASK. In October, Bornstein died, at age 74. A few days later: XOXO JOE, how Bornstein signed emails. The firm’s marketing director says they’ll keep posting CALL JOE. For one, it’s their phone number. Plus, he adds, “it’s kind of Maine folklore at this point.”

Downstairs, on the front door, there’s another sign, printed on a sheet of paper, explaining that 477 Congress is closed to visitors. Four years ago, debt collectors seized the building, which had fallen into disrepair. Chris Rhoades, a Falmouth-based developer, is part of a group that bought the building last year and has plans for a historic renovation — and possibly for updating the rooftop sign with newer technology. Regardless, he says, they’ll keep the lights on.

Time and Time Again

Ask a few dozen Portlanders what phrase they most associate with the ever-changing sign atop the city’s Time and Temperature Building, and there’s one answer you’ll likely hear more than any other: CALL JOE. We were working on this piece when we heard that attorney Joe Bornstein had died, at age 74. Bornstein, who opened his law practice in the Old Port in 1974, became one of Maine’s most well-known lawyers in part because of his firm’s concise advertising over the last decade on the iconic sign. Photographer Corey Templeton has perhaps paid more attention to the sign than any other Portlander. For about the last five years, he has photographed it from many, many angles for the Bornstein law offices’ Time and Temperature blog, where curious sign-gazers can go for more info on the sometimes cryptic messages it broadcasts. “I’ve probably taken a few hundred photos of that building,” Templeton says. “If you can photograph a thing 200 times and try to keep doing it differently, it’s a great creative exercise.” Templeton, who shared some of his photos for this article, was a natural pick to document the iconic piece of skyline: in 2008, the downtown denizen started his own Portland Daily Photo blog, a project he continues to update (although slightly less than daily) on his Instagram feed.