By Virginia Wright

Photos by Michael D. Wilson

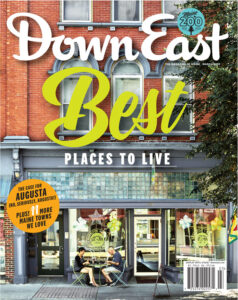

See the 11 other Maine towns in our 2020 Best Places to Live feature

Growing up in Maine’s capital in the ’80s and ’90s, Justin Fecteau thought of Water Street, the heart of downtown Augusta, as a museum that was always closed. “It was my parents and grandparents telling me how it used to be,” he says, “a place filled with stores I never got to visit.” His family’s Water Street was D.W. Adams department store, Sears, and Woolworth. It was cars parked along both sides of the street. It was the Colonial Theater, its marquee ablaze with racing white lights.

His Water Street was a corridor of shabby, empty storefronts and cars moving through as if they couldn’t get out of town fast enough.

It was still pretty grim in 2013, when, after an Army stint in Iraq, Fecteau returned home to Sand Hill, a working-class neighborhood high above the Kennebec River. He took a job teaching high-school German. His wife, Grace, a fellow Iraq vet from Los Angeles, managed finances for a government nutrition program. Weekend nights, when Water Street was dark and deserted (and, Grace says, a little scary), they’d head to neighboring Hallowell, the region’s longtime cultural center, for dinner and live music.

“But in the past two years,” Justin says, “we’ve probably been to Hallowell just four times. Don’t get me wrong, I love Hallowell, but we don’t need to leave the city anymore. Everything we want is right here, and it’s only getting better every day.”

The Fecteaus, both in their early 30s, are cozied up on a couch by the fireplace in Huiskamer Coffee House, the café they opened a year ago on Water Street. Huiskamer is modeled after the Fecteaus’ favorite coffeehouses in the Netherlands, where they often went on leave from their base in Germany (pronounced “house-kammer,” the name is Dutch for “living room”). It’s one of more than a dozen restaurants and bars to open in the compact downtown in the past three years, and on this sunny winter morning, there isn’t a seat to be had.

| Population | 18,626 |

| Median age | 45 |

| Median household income | $40,181 |

| Families living below poverty line | 14% |

| Walk score | 25/100 |

| GreatSchools rating average | 5.75 |

A downtown Augusta revival had been on a slow simmer for about a decade, ever since Tobias Parkhurst, then 30, retired from professional skateboarding and came home to take over his family’s Augusta glazing business. Unable to find an apartment he liked, he bought a 19th-century, three-story brick office building on Water Street, converted the upper floors to flats, and became a live-in landlord. It attracted attention to downtown’s architecture, which prompted more apartment conversions by Parkhurst and helped lead to a 2017 National Register of Historic Places listing for a quarter-mile stretch of Water Street — a designation that comes with significant tax credits for property owners who rehabilitate old structures. Now, in addition to the restaurants and bars, there are 39 apartments, all occupied, in what had been vacant, upper-floor office space, and further renovations are frenzied: the number is on track to hit 100 by year’s end. Meanwhile, the 107-year-old Colonial Theater, which showed its last movie in 1969 and has twice been saved from the wrecking ball, is cloaked in a curtain of plastic sheeting as construction workers refurbish the exterior, the first phase of a three-year project to restore it as a performing-arts center.

What’s happening here, the Fecteaus say, isn’t just the resurrection of a commercial district. It’s the creation of something new — an urban neighborhood, where people live, work, shop, and play. The folks who are making it happen are mostly native sons and daughters, many of them in their 30s and early 40s, who see potential where prior generations saw failure. “Grace and I aren’t the pioneers,” Justin says, “but we caught the wave.”

Downtown Augusta proper is tiny — less than half a square mile along the west bank of the Kennebec River. And it’s a bit elusive. Travelers heading to the capitol complex from the Maine Turnpike, to the west, don’t even see it. Drivers coming from the east catch a glimpse of its brick-and-granite profile from high above the Kennebec on the Memorial Bridge. Getting there can be intimidating to those unfamiliar with Augusta’s infamous traffic rotaries, one on each side of the river, flinging cars in all directions like a centrifuge. Plus, for nearly 75 years, traffic flowed one way on Water Street. Drivers headed downtown from Old Fort Western, Augusta’s most prominent cultural attraction, were directed north, away from the commercial district.

Downtown’s rise and fall mirrors that of other Maine mill towns. With textile, shoe, and paper factories along the Kennebec, Augusta grew and flourished through the 19th century and well into the 20th. In the late 1800s, it was one of the country’s leading mail-order publishing centers. So many journals were being sent out of Augusta — 1.2 million a month from the E. C. Allen company alone — that, in 1886, the federal government built a new post office to handle them. The formidable, multi-turreted Olde Federal Building remains Water Street’s most striking structure, and owner Andrew LeBlanc, one of those 30-something entrepreneurs investing in downtown, plans to turn his attention to it once he finishes his current project, the renovation of the elegant Vickery Building, which was built in 1895 for publisher and three-term mayor Peleg O. Vickery.

For decades, the Edwards Manufacturing Company and its successor, the Edwards Division of Bates Manufacturing Company, was one of Augusta’s largest private employers, with a textile mill at the north end of downtown. Most of its hundreds of Franco-American laborers lived in wood-frame tenements and modest houses just up the street, on Sand Hill. Their more affluent bosses lived alongside industry leaders and state-government muckety-mucks in the dignified West Side, an easy stroll from Water Street.

After the Maine Turnpike was extended to Augusta in 1955, the face of the city changed. Big Victorian homes and elm trees that lined Western Avenue, a main thoroughfare from the turnpike to Water Street and the capitol, gave way to shopping centers. The damage to downtown was swift. The city’s first organized revitalization effort was launched in 1978, but more blows followed. In 1981, manufacturing ended at Edwards Mill. Developers eyed the building for offices and shops, but it burned to the ground in 1989. Another major employer, Statler Tissue, with more than 500 employees, closed its plant in 1995.

Although downtown suffered, Augusta as a whole weathered the manufacturing exodus better than other factory towns. The capital has poverty levels higher than the statewide average, and it struggles with issues, like crime, that tend to accompany economic disadvantage. But thanks to the shopping centers, the city has remained central Maine’s retail hub, says Keith Luke, Augusta’s deputy director for development services. Even more significant are the state government offices, law and lobbying firms, and MaineGeneral Health hospital, which triple Augusta’s population of 19,000 people during the day and render the city, to some extent, recession-proof. Luke wishes more of those commuters lived in Augusta, which means addressing the city’s serious shortage of market-rate apartments. Water Street, where the apartment vacancy rate is now zero percent, is proof that people want to live in town, Luke says, adding that the success of those developments may have rippled to Western Avenue, where a 50-unit apartment project is under consideration. “Who could have predicted that 10 years ago?” he asks.

Chances are, you’ve heard the unflattering nickname: Disgusta. I confess, I’ve uttered the epithet a few times myself. Though I appreciate the capitol complex, with its lush riverfront park and stately government buildings, my impression of Augusta was, for years, that of the traveler passing through: Our state capital was two infernal rotaries, a constellation of strip malls, and rundown neighborhoods. When I finally did find my way to Water Street several years ago, a wave of sadness washed over me: Why were these fine old riverfront buildings so neglected?

Then, two years ago, I allowed my frustration with our capital’s appearance to creep onto these pages when I referred to Augusta as “Hallowell’s office” and implied it had little to offer beyond big-box stores and chain restaurants. That’s when I heard from Michael Hall, the executive director of the Augusta Downtown Alliance (ADA), a public-private organization dedicated to attracting businesses and promoting the city to visitors. In an email, he told me I’d gotten Augusta wrong. Exciting things were happening, he insisted. “All too often the people have this notion of ‘Disgusta,’” he wrote, “and we have had to work overtime to dispel it.”

Turns out, downtown is more than a job to Hall. He lives there, in one of those new Water Street apartments, a few doors from his office in the Olde Federal Building, which is where we meet on a mild winter morning. Hall tells me he was living in Jacksonville, Florida, winding down a marketing assignment for the Wounded Warrior Project, when he made his first-ever trip to Maine to interview for the ADA job, in December 2015. On the drive from the airport in Portland, board members took him through the busy, well-preserved villages of Gardiner and Hallowell. “This is what we want,” they said.

“Then we came downtown,” Hall tells me, leaning forward in his chair. “It was past 5 and kind of dead, but what struck me was how different this place looked. For a town this size, the buildings are huge — it looks like a city. There’s an eclectic nature to the buildings — Romanesque revival, Italianate, Second Empire, neoclassical. I love architecture, and I could tell this city was unique.” This from a guy who spent a year in the medieval city of Edinburgh, earning a degree in architectural conservation.

Hall has since witnessed a synergy develop out of hometown pride, a strong economy, the shop-local/eat-local trend, and public support for private investments. A few years ago, for example, the city relocated a bus depot on a prominent downtown corner and replaced it with a park. Then, last summer, the city reopened Water Street to two-way traffic, at ADA’s urging. “It was the right thing to do,” Hall says. “We were losing a lot of people who didn’t know how to get downtown. Now, it feels more like an intimate city.”

Perceptions are the biggest hurdles to clear in getting people to embrace downtown again, Hall finds. “People who grew up around here remember when downtown was a retail mecca. Downtowns don’t work like that anymore. It’s niche shopping now. Then, you have the people who grew up when downtown was in decline. They’re stuck in a negative mindset and haven’t been here in years.”

ADA’s board members, a mix of mostly young developers, business owners, and artists, respond to such negativity with self-deprecating humor: one of the organization’s marketing tools is a T-shirt bearing the slogan “Don’t Dis ’Gusta.” At times, Hall sounds like a born-and-bred Augustan himself. “Don’t stay in Portland,” he writes in the introduction to his 2018 book, Augusta: The Best Little City in New England. Seriously. “They’re a bunch of snobs anyway: ‘Oh, we have 18 craft breweries and a variety of artisanal cheese shops.’ Big whoop. We’ve got three Dairy Queens.” Ostensibly, his book is a travel guide, but really, it’s a snapshot of the collective spirit created by fledgling entrepreneurs taking risks and feeding off each other’s enthusiasm in a retail environment that’s pretty much a blank slate.

It can be exhilarating to be the underdog. I hear this several times, though not in so many words, when Hall takes me around to some of the businesses that have opened in the past few years: Otto’s on the River, a restaurant specializing in seafood and pasta and making the most of its riverfront location with an outdoor deck. Water Street Barber Co., giving fade haircuts and hair tattoos in an old-timey atmosphere. Raging Bull Saloon, where customers sit at the bar on real saddles and listen to live country music coming from a stage that looks like the porch of a Tennessee mountain cabin.

In Cushnoc Brewery, we find Tobias Parkhurst, who got this ball rolling when he built himself an apartment a decade ago. “People tell me that I got in at the right time,” he says, “but I wasn’t thinking about the prospect for future success. I just needed a place to live. I couldn’t find an apartment, so I made one. When I couldn’t find a nicer apartment, I made another. It just made sense at the time.”

It’s his passion now. Not only is he a partner in the brewery, which is hopping today, as it has been nearly every day since it opened in 2018, he’s the owner of the 1932 Moderne-style building it’s in, as well as four other Water Street buildings. His family has jumped into the redevelopment game too. His dad, Richard Parkhurst, has renovated two buildings for retail and apartments and is the president of the board overseeing the Colonial Theater restoration. His sister, Soo Parkhurst, recently bought three buildings, also for retail and apartments. Soo’s husband, Sean McLaughlin, has partnered with the Cushnoc Brewery team to open State Street Lunch, a gastro-pub, in March.

“The barrier to entry here is so much lower than other parts of the state — I couldn’t do this in Portland,” Parkhurst says. “It’s cool to be in a place where you can make a difference. And yes, you can still find plenty of shoddy-looking buildings that need attention, but that’s just opportunity for the next guy.”

Last year, Matt Pouliot, a Republican state senator representing Augusta and several surrounding towns, visited Austin, Texas’s capital, and was “blown away” by its beauty. It got him thinking about Maine’s role in caring for its capital city. “What can we do to make it more of a destination and to shake the appellation — I hate to even say it — ‘Disgusta’?”

Maine’s capital belongs to all of us, not just the people who live there, a point that Pouliot, in his mid-30s with a real estate business downtown, has been pressing with his legislative colleagues as he works to improve pedestrian connections between the capitol complex and downtown. One idea is to build a path from Capitol Park to the Kennebec River Rail Trail, which runs between downtown Augusta and Gardiner. Another idea is to reinstate the Capital Riverfront Improvement District, a city-state partnership formed after the Edwards Dam was removed in 1999. The district helped pay for, among other things, the development of Mill Park on the Edwards Mill site. Pouliot’s talking with the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development about getting funding for the district in the governor’s 2021 budget.

“It’s a little unusual for the legislature to appropriate funds to a particular community, but, as the capital, we host the state government,” he says. “It occupies a lot of property that’s not taxed, and that hampers our ability to make investments in our community. Some may say, well, Augusta benefits from all the jobs that come with being the capital. That’s true, but at the very least, we can all agree that we should be proud of our capital.”

Pouliot and his wife, Heather, ADA’s chair and a newly minted city councilor, recently bought a Water Street building, which they’re renovating into apartments on the upper floors and, they hope, a grocery downstairs. But there are many stores like this in Maine. He won’t offer specifics, but the cost to develop their building far exceeds its appraised value, which he said is typical of many of the downtown projects to date. “Investors outside of Augusta would probably look at them and say, ‘This doesn’t make a lot of sense.’ What you have here are people who are not necessarily interested in making a quick buck. They’re passionate, and they want to contribute to the community.”

Not long ago, Pouliot’s mémé and pépé, lifelong Augustans now in their 90s, told him they hadn’t seen this much excitement about downtown since before the malls sucked the life out of it. “New life is being breathed in, but it’s a different kind of life,” he says. “It’s not big department stores. It’s human beings living here and calling it home.”

What’s What on Water Street

Cushnoc Brewing Co.

Cushnoc is two venues in one: a family-friendly restaurant serving snacks and wood-fired thin-crust pizzas (try the Fort Western, a white pizza topped with crispy pancetta and peppery arugula) and a basement tasting room where flights of hoppy IPAs, velvety porters and stouts, and fruity ales are served at a community table. The vibe is industrial chic. Restaurant: 243 Water St. 207-213-6332. Tasting room: 40 Front St. 207-213-6672.

Downtown Diner

Sometimes you just want a simple, old-school BLT. Downtown Diner’s got one, with thick bacon and homemade bread. It’s got a lot of other no-nonsense but exceptionally good food too (think fried-egg sandwiches, waffle platters, and grilled pastrami and cheese), and the waitstaff is super-friendly. 204 Water St. 207-623-9656.

Merkaba Sol

David Hopkins and Bishop McKechnie have been selling gifts and “tools of enlightenment” — crystals, incense, and the like — since 2010, which makes them pioneers of the new Water Street. It’s a fun place to browse whether you’re a believer in spiritual healing or not. 223 Water St. 207-922-9916.

Oak Table & Bar

After a stint as chef-de-cuisine at Portland’s Congress Squared and an appearance on Chopped, Eli Irland came home to Augusta, where he creates an ever-changing menu of small plates using fresh, local ingredients — dishes like seared black bass, charcuterie plates, and fiddlehead cheese, all crafted to pair with bartender Kyle Neilson’s rotating cocktail menu. Craft beers and a large selection of scotches too. 233 Water St. 207-812-0727.