By Dan Otis Smith

From our February 2018 issue

One evening in the spring of 2015, I drove down a wooded road north of Rangeley Lake to visit the 175-acre estate known as Orgonon. I was there to interview Kevin Hinchey, then a co-director of the Wilhelm Reich Infant Trust, named for the scientist and Austrian expat who’d purchased the property in 1942 and conducted research there until 1957, the year he was sentenced to federal prison and died in his cell.

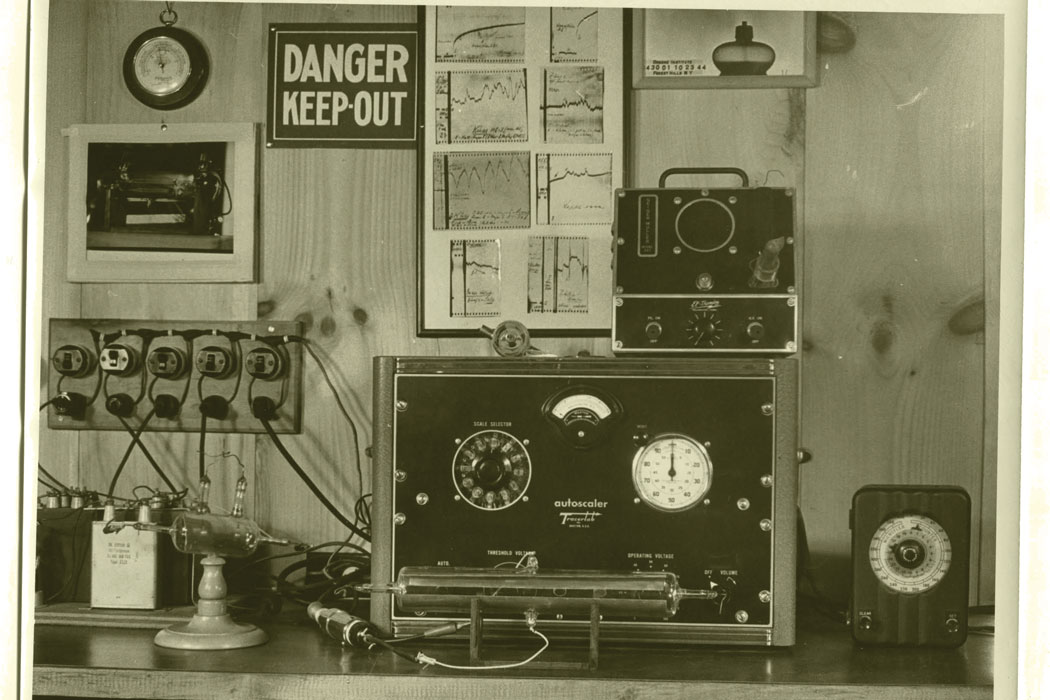

Hinchey was staying in a rustic cabin across the street from the flat-roofed, fieldstone citadel that Reich called his Orgone Energy Observatory. It was there that Reich performed experiments to determine the nature and practical application of what he’d dubbed “orgone energy,” an all-permeating cosmic life force that the psychotherapist-turned-biophysicist had discovered years before, while seeking a biophysical manifestation of the Freudian libido. Now a museum, the building houses Reich’s books, equipment, artwork, and inventions, including several orgone energy accumulators — walk-in boxes like freestanding closets, in which one can soak up high dosages of orgone for its therapeutic and medicinal benefits. Scattered elsewhere around the property are a trio of cloudbusters, steampunk-looking arrays of hollow copper pipes mounted atop turrets, thick cables trailing off the back. These were used to suck excess orgone from the atmosphere to incite rainstorms — and, in Reich’s later years, to disrupt the comings and goings of the UFOs he suspected were polluting Earth’s orgone field.

During Hinchey’s 14-year tenure as a director (he stepped down in late 2016), the now–63-year-old Connecticut native visited Orgonon monthly to help administer Reich’s archives, write for the trust’s publications, organize conferences, and give the occasional museum tour. He’s been visiting Rangeley since childhood; in the ’70s, a run-in with some college kids on a pilgrimage to the museum had first piqued his interest in Reich. He read everything of Reich’s he could find, from 1927’s The Function of the Orgasm, which established Reich as a promising Freudian acolyte, to 1933’s The Mass Psychology of Fascism, which got Reich chased out of Germany, to 1938’s The Bion Experiments on the Origins of Life, which prompted the first loud accusations of quackery from the scientific establishment — but not the last.

When I sat down with Hinchey, he showed me a fat binder containing an outline of a documentary he was ready to undertake, a project he described as “the first factually accurate film about Reich.” He said he’d grown sick of the distortions and inaccuracies that tend to accompany popular coverage of Reich — suggestions that he was a sex cultist, dismissals of his research by folks who’ve never read it, accusations (false, says Hinchey) that Reich claimed he could cure cancer. He wanted to set the record the straight, he said, but it would take a lot of work and money — and frankly, he wasn’t sure it was possible.

Fast-forward three years: Hinchey’s film, Love, Work and Knowledge: The Life and Trials of Wilhelm Reich has just wrapped its New York City premiere, and its creator hopes the film will make the festival rounds in 2018. The audience in NYC included 200 or so of the 1,000-plus Reich enthusiasts who donated some $400,000 via online crowdfunding campaigns to get the doc made — allowing Hinchey to shoot on location everywhere from Rangeley to Tucson to Vienna to Oslo. So who are these admirers of a long dead, questionably reputable scientist? What about Reich stokes their fascination? And does the orgone energy still flow strong in pockets of rural Maine?

Wilhelm Reich grew up in the early 20th century in an eastern province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After an army stint in WWI, he went to Vienna to study medicine and met and befriended Sigmund Freud. Like Freud, he was preoccupied with questions of sexuality and its relationship to physical and mental health. He was taken with Freud’s early concept of libido and how it might express itself through neuroses. Reich’s therapeutic experiences convinced him that sexual activity — and its repression — had critical links to psychological health. Getting patients to shamelessly experience gratifying orgasms became a central goal of his therapy. Reich’s takes on psychoanalysis and sexual freedom dovetailed with his Marxist leanings — capitalism, he felt, was both politically and sexually repressive — and he set up free clinics with info on sexual health, plus a mobile clinic stocked with literature and contraceptives.

“Reich spoke from his soapbox about the dangers of abstinence, the importance of premarital sex, and the corrupting influence of the family,” biographer Christopher Turner writes in his 2011 book Adventures in the Orgasmatron: Wilhelm Reich and the Invention of Sex. Turner and plenty of others credit Reich with laying the groundwork for the sexual revolution of the later 20th century.

Reich practiced psychoanalysis in Berlin a while, then fled to Norway as the Nazis came to power. There, he started dabbling in lab science, searching for some kind of measurable libidinous energy. He attached electrodes to volunteers’ erogenous zones and gauged their electrical charge with and without stimulation. He turned to microscopy to find evidence of libido in the smallest living things and noted a similarity between the convulsions experienced in the human orgasm and the internal movements of microorganisms. As he watched organic materials disintegrate under his microscope, he claimed to see new particles form that pulsated with a mysterious energy he called “orgone.” He called the particles “bions” and described watching them bind together to transform into protozoa — claiming, in other words, to have witnessed the microscopic origins of life itself.

The European scientific community did not reach the same conclusions. Critics shrugged that Reich had simply discovered bacteria that had found their way into his cultures. He was mocked as a charlatan in both academic circles and the popular press, and some of the public ridicule was accompanied by a whiff of anti-Semitism. It was under a cloud that Reich left Norway for the U.S. in 1939, shortly after the Nazis invaded Poland.

.

Renata Reich Moise lives in Hancock with her husband and has three orgone accumulators that she uses only occasionally, for things like minor burns or insomnia. Two she made herself: a metal bowl covered with layers of wool and steel wool (the former pulls orgone from the atmosphere; the latter radiates it towards the user) and a heavy blanket containing similar materials.

The third is a full-size vintage accumulator that abuts the Moises’ greenhouse. Renata let me sit inside, where a small plaque reads, “Wilhelm Reich Foundation.” After a few minutes, I sensed, more than heard, a faint buzz, which I told myself was the friction of steel wool scraping the booth’s rickety walls. Outside, I heard the whoosh of wind or sea. When I stepped out again, I felt fine. Calmer maybe? Centered?

Reich claimed to see new particles that pulsated with a mysterious energy he called “orgone.”

Renata was born in 1960, three years after her grandfather’s death in prison. Her mother, Eva, Reich’s eldest daughter, worked alongside Reich in Rangeley, and her father, William Moise, worked as Reich’s assistant and sort of PR rep. Renata grew up using orgone accumulators and watching her dad alter weather systems with one of her grandfather’s cloudbusters.

These days, she’s a certified nurse midwife, and early in her career, she says, there were times that she butted up against establishment attitudes about orgone. Once, when she was a student, a visiting lecturer used her grandfather as an example of a quack. Another time, she included Reich’s perspective on the roots of cancer in a paper, and every page came back crossed out with a red “X.”

“Those kind of things, when they happen, you can go two ways,” she says. “I could have said, ‘I quit. I’m not going through this modern medical thing.’ Or, the reality is, you’re 21, and you need to be able to make a living.”

Still, she says there’s no tension between the science of her upbringing and of her profession. Renata likens orgone to qi, the ancient Chinese concept of life force that’s managed in acupuncture. “The knowledge I have about how emotions affect the body is pretty easy to translate into working with a woman in labor,” she explains. “The piece I don’t merge is the accumulator — and that’s okay. I’m not on any kind of mission to do that.”

It was the accumulators that brought about Reich’s downfall, along with McCarthy-era suspicions and social mores. Reich sought peace in Rangeley — he boasted of ushering in a new “era of atomic energy . . . not in your inferno, but in my quiet, industrious laboratory in a far corner of America.” And he found supporters there, as well as converts to orgone therapy. But Rangeley had a small town’s rumors and prejudices. The night Eisenhower was elected, in ’52, a crowd marched past a house where the Reich family was staying, chanting, “Orgy, orgy! Come out, you commie!”

Some news articles portrayed Reich as a kook and/or subversive, and these caught the attention of the Food and Drug Administration, which opened a file on Reich, suspicious that his orgone accumulators represented a “fraud of the first magnitude.” Over the course of a decade, the agency spent millions investigating Reich — on surveillance, accumulator purchases, tracking and interviewing patients, and repeated, unannounced visits to Orgonon. They deemed the accumulators medically worthless. In 1954, Reich was served a summons to answer the FDA’s call for an injunction prohibiting interstate shipment and advertising of them.

But Reich didn’t show, and the injunction was enacted in his absence. When one of Reich’s students was caught bringing accumulators to New York some time later, Reich was convicted of contempt of court. The FDA orchestrated the destruction of the accumulators at Orgonon and, deciding they qualified as advertising, burned thousands of his books and journals. Reich was sentenced to two years in prison and died of heart failure eight months into his sentence.

Such cloak-and-dagger drama over a harmless wooden box may seem ridiculous today, but Renata has heard stories all her life of the FDA’s offensive and its aftermath. “It was horrible at the time,” she says. “For my parents, it was a horrible time.”

.

What really bothers Hinchey is the FDA’s assumption that Reich was not only a fraud but a pervert, the way the agents’ suggested they were on the verge of busting up some kind of sex ring. He’s also rankled by the pop mystique that’s evolved around orgone accumulators. Bohemian types like William S. Burroughs and Norman Mailer were enthusiasts, sometimes describing the box as if it were a mystical aphrodisiac. In Sleeper, Woody Allen famously parodied orgone accumulators with a device called the Orgasmatron. Hinchey can hardly say the word without sighing and rolling his eyes.

The ranks of Reich’s modern-day defenders are modest and motley, Hinchey says, “sort of a tortured landscape, ranging from serious scholars to people who are completely mystical and uninformed.” But what unites New Age-y therapists and radical lab scientists and sex researchers and UFO conspiracists and others is a desire to see their martyr redeemed — and, one suspects, their own convictions validated. Hinchey’s donors weren’t just funding a movie, as they see it; they were righting a wrong.

A Reichian reappraisal may have a head of steam. The film comes on the heels of a 2015 book, published by Harvard University Press, calling for recognition of Reich’s rigor in the lab, if not his discoveries. Author James Strick is a history of science professor, a co-director of the Reich Trust, and a consultant on the film. He realizes the entrenched skepticism that the Reich-curious are up against. “As a young scientist, you might pick up Reich’s book and be interested,” Strick says, “but your PhD advisor says, ‘You don’t want to get involved in this unless you’re a very established scientist.’”

Hinchey is more optimistic. “I hope that young, college-educated people will see this film and read his books,” he says, “that they’ll ask, ‘How does Reich explain his own life and work?’ and not go looking elsewhere.”