By Jesse Ellison

Photos by Sofia Aldinio

From our September 2025 issue

It all started, Usha Beaudoin says, with a pretzel. In the summer of 2020, the early months of the pandemic, she was on Matinicus Island, where her mother’s family goes back nine generations, with her husband, Ryan Pelletier, and their six-month-old daughter, Ruby. Pelletier had lost his job with a study-abroad and international-exchange organization when global travel shut down, and Beaudoin was on maternity leave from her work as a medical assistant, so they decided to spend the whole summer out there, like she did as a kid.

Twenty-two miles offshore, Matinicus is Maine’s most remote island to host a year-round population. From November through March, the ferry out of Rockland makes the trip just once or twice a month, and even in the warmer months, it only runs four times, so the way most residents get back and forth is by plane. Penobscot Island Air operates what amounts to an air-taxi service out of Knox County Regional Airport, in Owls Head. There’s no ID check or TSA screening at the terminal before boarding, but there is a mini fridge stocked with Pepsi, Bud Light, and High Noon hard seltzer. The planes are single-prop Cessnas, and if there’s weather, as there often is, they don’t go. When that happens, the mail doesn’t arrive. Neither do islanders’ Hannaford to-go groceries, and there are no stores (and certainly no restaurants) out there.

That summer on the island, Pelletier made pretzels from scratch. They came out well, but the island had been socked in for three weeks, with no planes coming or going through the fog, and Beaudoin and Pelletier had run out of salt — and what’s a pretzel without salt? “Well, but, we’re surrounded by salt,” Beaudoin remembers thinking. “I grew up here. I’ve walked the rocks. I’ve seen wild salt. If you walk around the rocks in the summer, you’ll see little crevices filled with it.” So she dug out her old camping stove, went down to the shore, filled a pot with some seawater, turned on the heat, and sat there knitting and waiting. She wasn’t confident in what she was doing, and in the process she shattered two of her mother’s Pyrex dishes by pouring cold water in already-hot containers. But then, eventually, it worked. The water evaporated and all that remained in the pot was a crust of salt. The pretzels were complete.

Clockwise from top left: approaching Matinicus on a flight with Penobscot Island Air; Matinicus’s working waterfront; rowing with the family from a rocky island beach; Beaudoin cooking outside.

After that, Beaudoin became fascinated by the process of turning an infinite resource — one quite literally surrounding her — into a substance, beautiful in and of itself, that makes everything taste better and never goes bad. It seemed to her like some kind of magic that something so chemically and physically complex could also be so simple to produce. Within a year, she had decided to start a salt business. “I wanted something that I could continually learn from,” she told me recently. “And making something that’s so inherent to being human as salt, plus the ocean connection . . . I love it.”

From the start, it was clear to her that, if she was going to do this at all, she was going to do it on Matinicus. In the late 19th century, hundreds of people stayed on the island year-round, straight through the winter, but not many more than a dozen do now. One solitary child attends classes in the one-room schoolhouse. The postal service occasionally weighs whether to shut down island mail service. Subtraction has long been the trend, and Beaudoin wanted to add something. Maybe a single post-office box affiliated with a new business could make a difference, she figured, and regardless, it just felt right to her.

The summer she and Pelletier had there with Ruby as a baby had been transformative. “I needed that time,” she says. “It didn’t hit me until after COVID that I didn’t need to live the way I had been. I thought that people just hated their jobs and lived for the weekends. It never occurred to me that that didn’t have to be life. The summer we spent out here, I was like, ‘This is the pace of life that really makes me feel like myself.’ And I wanted this for Ruby too.”

Beaudoin is, unsurprisingly, not the first person to think of making a business of sea salt in Maine, although few people have actually attempted it. In the 1990s, Steve Cook was unemployed and trying to come up with a business idea when he noticed a jar of sea salt from France on a shelf at a health-food store. He did a little research and couldn’t find anyone making sea salt anywhere in the U.S., let alone around here, so he launched Maine Sea Salt Co. in Harpswell. In 2006, he relocated to the Washington County town of Marshfield, using water from nearby Bucks Harbor. In the absence of much competition, the business grew to comprise 10 greenhouses, each 200 feet long, where seawater could evaporate aided by solar heat.

Over time, Cook started packaging specialty salts, like hickory- and applewood-smoked varieties, and he found it impossible to produce too much salt, never managing to keep up with demand from retailers and direct customers around the country. Cook died last year, though, and the company folded soon after. By then, others had gotten into sea salt. Maine Salt Farm, a small operation in Cape Elizabeth, got off the ground in 2015. And Lauren Mendoza, along with her aunt, Cathy Martin, started Slack Tide Sea Salt, in York, in 2019.

Most salt in stores is table salt, mined from underground deposits created by ancient seabeds and processed to a fine grain. It dissolves quickly in cooking and pours easily from a shaker. Sea salt’s chemical composition is more or less the same, but it’s usually employed as a finishing flourish atop a dish, not just for flavor but for the visual impact of the large, irregular crystals and the flaky, crunchy texture produced by slow evaporation. Mendoza couldn’t believe, considering Mainers’ penchant for local ingredients and the many ties that bind Maine’s economy to the sea, that sea salt wasn’t a more common business. She had reached out to Cook early on with questions, since there was nobody else to ask. “He was the pioneer,” she says. “And he could not have been kinder or more supportive.”

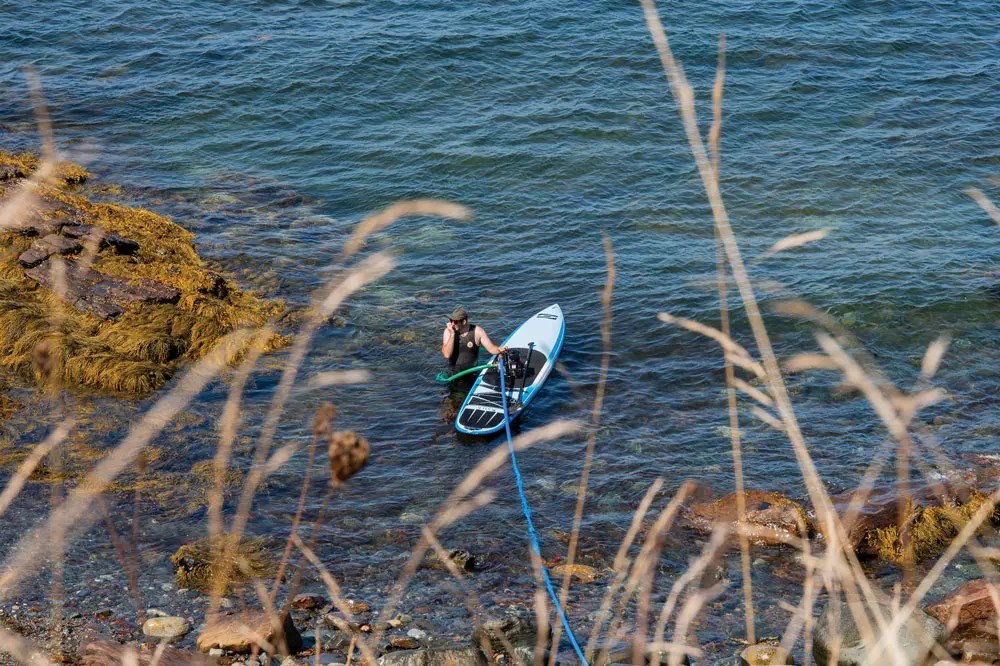

Clockwise from top left: To move seawater up the bluff to the tables in their greenhouse, Beaudoin and Pelletier use a small pump and a 400-foot-long hose. Then, solar heat does the rest of the work, slowly evaporating the water and leaving behind salt.

Even today, only a handful of salt producers operate in Maine, and Mendoza laughs when she explains why: “It’s really freaking hard!” she says. “You have to be in love with it to do it. It’s not going to make you rich, and it’s not going to be easy. If you’re doing it with greenhouses, you’re at the mercy of Mother Nature, which adds a whole other element because weather in Maine is unpredictable and you just have to roll with it.”

Beaudoin realizes that getting into such a difficult industry probably seems quixotic, especially on Matinicus, with its incumbent logistical hurdles — she plans to ship orders of salt off the island on the mail plane, using the U.S. Postal Service. “You’re crazy for starting this business right now,” one friend told her. Her response, she says, with a knowing sort of grin, was to point out that she had dealt with considerably more complicated situations in the past.

Beaudoin was born in India, probably in the city of Pune and probably in 1987. Her parents, Jeanette and Ray, adopted her in 1992. Jeanette is from Matinicus, a member of the Youngs, the second family to inhabit the island, back in the 1700s. Jeanette and Ray, like most island families, also had a house on the mainland, where they could spend the winters, but they held onto their Matinicus properties, attachments, and sense of identity. Beaudoin and her brother, who was also adopted from India, grew up as island kids. They left the house every morning on foot or on bikes and joined the other kids in roaming free, convening at whichever home was convenient for lunch, collapsing at night, and doing it all over again the next day.

Clockwise from left: scooping formed salt crystals from the evoporation tables in the greenhouse; the end product is large, irregular crystals; Beaudoin, Pelletier, and their daughter, Ruby, reaching for finishing salt.

Only in middle school, after being assigned a family-tree project, did Beaudoin learn more about the circumstances of her adoption. She had been a street kid — not uncommon in a place where public resources were scarce and orphanages were stretched thin. Desperately skinny and malnourished, and suffering from severe lead poisoning, she was even on the news in Pune, featured as a child in need of someone to claim her. Nobody did. “I was cute though,” Beaudoin told me recently, sitting on a rocky beach on Matinicus’s southern shore, eating lobster rolls and carrot-cabbage slaw. Eventually, someone from one of the orphanages got her some care, taking her to the doctor and shepherding her along to a level of health she needed to have a chance at international adoption.

In Maine, in those pre-digital days, Jeanette and Ray paged through a book of potential adoptees and picked Usha. Four years old, speaking only Marathi, she arrived at Logan International Airport, in Boston, where she met her new family, a welcoming committee of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Two weeks later, she started school in Durham, where Jeanette and Ray had their mainland home.

Beaudoin’s first trip to Matinicus imprinted firmly on her mind. She’d just taken her first plane ride a short time earlier, flying halfway around the world, and now found herself on a small, plodding boat, heading way out to sea. “I remember just being like, ‘What is happening?’” she says. Sometimes, she looks at Ruby and imagines what it would be like to pluck her from Maine and drop her in the middle of, say, Japan. It’s almost inconceivable.

When she thinks back on her traumatic first years in India, followed by the shock of sudden relocation, she says she feels, no pun intended, “a little bit salty.” Up until high school, she and her brother were the only two kids in school with brown skin, and none of what she went through was easy. It was also, she says, a lucky turn of fate, and she credits the whole experience with instilling a certain resilience and hardheadedness. And Maine became home. Today, she’s so close with her parents that they live on adjacent properties in Durham. And when I visited Matinicus, I found them all sharing Jeanette’s no-frills family home. It’s near enough to the airstrip that a running family joke is they hope a plane someday clips the roof so someone else can foot the bill for a replacement.

When Beaudoin and Pelletier got married, eight years ago, Jeanette and Ray gave them a few acres of land as a wedding gift, atop a bluff on the island’s western shore. High above a rocky beach, the property faces the broad expanse of ocean between the island and the mainland, which the locals call America, as if to emphasize their apartness. They held their wedding reception there, and in the summer, they set up camp there with a 1965 Field & Stream camper, a composting toilet, and a tent platform. They hope to someday build a house that will allow them to live on Matinicus all year. But for now, the biggest structure on the property is a 32-by-30-foot greenhouse, for making salt.

The operation has come a long way since that first camping-stove experiment on the beach. For evaporating water, the greenhouse contains a series of wooden tables shaped like shallow brownie pans and fitted with food-grade thermal liners. There was a time when Pelletier and Beaudoin, doing trial runs, would fill five-gallon buckets on the shore, then carry them up the cliff along a precarious goat path. These days, wielding a set of Ruby’s old walkie-talkies to communicate with each other, one rows out in a boat while the other stays up in the greenhouse. A small gas-powered pump on the boat pushes seawater through a 400-foot hose, up the cliff to the greenhouse. The water passes through a filter, to remove any bits of organic debris or other detritus, then fills the tables, which can collectively hold 900 gallons, yielding about 225 pounds of salt — the output varies depending on the water’s salinity, which is affected by tides and depths. Pumping the water takes only about half an hour.

Afterward, Beaudoin waits. Evaporation takes as long as it takes. Sometimes that means an afternoon, but it often means closer to a month, depending on heat and humidity. “It’s hard to conceptualize waiting that long for something to be created,” Beaudoin said as she showed me the setup. “But I wanted to make something that was done naturally.” Plus, slowing down and remembering that things take time is part of what’s special to her about Matinicus. “One of the reasons I love it here so much is you feel like you can breathe,” she said. “There isn’t a need to be something or someone.”

Throughout the summer, much of the family’s time on the island is spent outdoors. On their property, in addition to the Matinicus Salt Farm greenhouse, they have an old camper, a composting toilet, and a tent platform.

Pelletier, who now works remotely as a data analyst for Maine Coast Heritage Trust, poured a bit of salt from a brown paper envelope into his palm. Some chunks were nearly a quarter inch wide, in a sort of pyramidal shape that salt connoisseurs call a hopper. The slow heating and cooling cycles, he said, allow delicate crystal structures to develop. Plus, the filter they use for the water lets microorganisms and trace minerals pass through, resulting in a product that resembles what the French call sel gris, with a distinctly soft-gray hue. In that way, this bright, briny salt, lingering pleasantly on the palette, is an expression of the specific marine environment around Matinicus.

In June, when I visited, Beaudoin and Pelletier were getting ready for a state inspection, the last step toward opening Matinicus Salt Farm. Beaudoin had reached out to Mendoza, who like Cook before, was more than happy to help, suggesting how to make sure all the details were attended to. A state inspector, though, had said they would need to install a septic system at the greenhouse, a requirement for all commercial kitchens and food-packaging facilities in Maine. Doing that on the island would have been exorbitantly expensive and taken years to complete. Eventually, one of Beaudoin’s neighbors offered to let her use her kitchen for packaging. When the inspector visited at the end of the month, they passed. The first thing Beaudoin and Ruby did was go to the post office and pick out a mailbox.

As Beaudoin sautéed chunks of steamed lobster in butter for lunch — it seems hardly a meal passes on Matinicus without lobster plucked from the surrounding sea — Jeanette couldn’t contain her pride talking about the community support her daughter has felt. “She’s part of Matinicus,” she said. “There are people on the island that have known her since she was a small child. So when she came up with this idea and got it off the ground, people thought it was wonderful, because she’s an island girl.”

When Beaudoin was still doing test batches, she’d give away salt to friends, many of whom passed some along to other friends. Pelletier mentioned that he’s heard people talk about how much they love being able to share a taste of Matinicus. A woman who also grew up spending summers on the island, Beaudoin added, messaged her and said the salt made her think of her grandparents, of summer, and of jumping in the ocean. “That’s exactly what I want,” she said, a smile spreading across her face. “People have these very vivid memories — the sun on their skin, the coolness of the ocean, the seawater drying on their face. Food does that. It’s such a connective thing. Smells and tastes are connected to places and people we love.”