By Andrew C. Miller

Photographed by Kevin Bennett

Foster Smith likes to say he has sawdust in his veins. As a young man starting out in carpentry 35 years ago, he preferred working alongside older craftsmen, so he could learn from their methods and experience. Four years ago, his affinity for traditional woodworking practices led him to purchase the machinery from a closed sawmill in Sedgwick that was known for making quartersawn, or radial-cut, clapboards.

Within a year of purchasing the equipment, Smith and his family (wife Loretta and twin sons Daryl and Daniel) were putting it to work as Maine Milling, in East Blue Hill. The equipment’s previous owner had offered to instruct Smith in the radial sawing of tree trunks, but he figured out the process on his own. “It’s just common sense,” he says, “like cutting out a wedge of cake.”

True, but that cake is 16 feet high and nearly 3 feet in diameter, and it weighs 3,000 pounds. It’s so big, you lay it on its side to slice it.

Maine Milling is the only mill in New England producing 16-foot-long quartersawn clapboards, using techniques similar to those that Colonial sawyers used. In fact, the equipment Smith now owns made clapboards for a restoration of the education and visitor center at the Paul Revere House in Boston, ensuring that the replacements matched the originals.

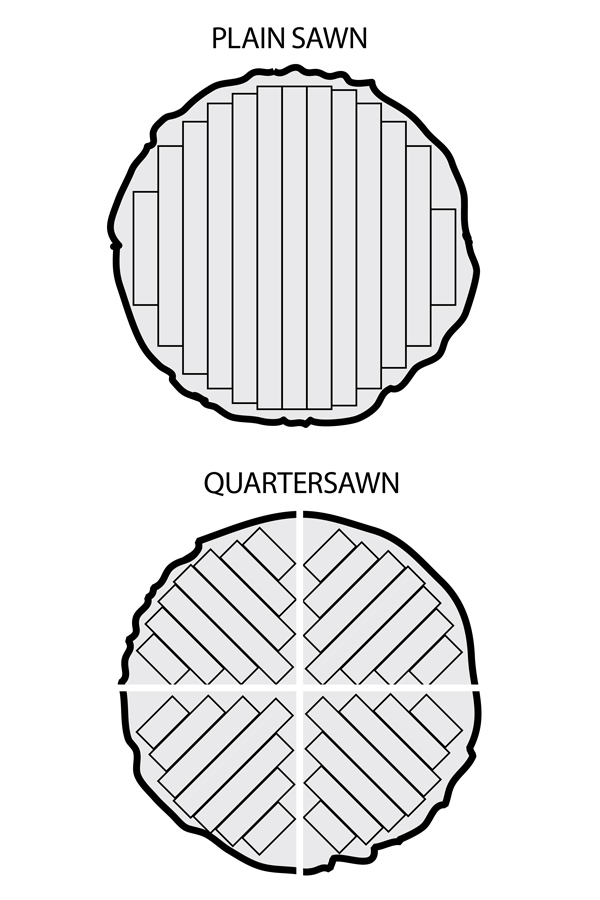

Quartersawn clapboards look different and wear better than the common plain- or flat-sawn boards found in most lumberyards. Because flat-sawn boards are made by repeatedly running the log from end to end through the blade at the same angle, the growth rings form ragged loops on the board’s face. Quartersawn boards, by contrast, are cut from multiple angles — think of those tall, slender cake wedges — so the growth rings run along the face in parallel lines. This vertical grain resists shrinking and warping and holds paint better than a flat grain.

Smith sources only blemish-free white pine from northern Maine. One log can yield up to 100 clapboards, each one 5½ inches wide and beveled, sloping from an eighth-inch thick along the top edge to a half-inch at the bottom.

Radial sawing is more time consuming and therefore more costly than plain sawing, but it results in a more durable (and some would say more attractive) board. “The slower you go with wood,” Smith says, “the longer it lasts.”