A DILETTANTE'S GUIDE TO THE FINE FEATHERED WORLD OF

By Nick Lund, Brian Kevin, Maggie Nevens, and Willy Blackmore

From our September 2019 issue

If you’ve ever caught your breath to hear a loon call up at camp, if you’ve ever stopped in your tracks to watch an osprey riding high on coastal thermals, if you’ve ever chuckled at a puffin making a crash landing on a grassy island knoll, then you know the experience of birds is inextricable from the experience of Maine. And you know you don’t have to be the kind of person who keeps a life list in order to find joy in the state’s avian abundance.

But among those who do — keep a lifelong, cumulative record of identified bird species, that is, and who travel to expand their lists — Maine is considered a top birding destination. Why? In a word: habitat. The state’s deciduous and transitional forests, its coastal and higher-elevation boreal forests, and its here-marshy and there-rocky coast all support distinctly different bird populations. And because it sits at the heart of the Atlantic Flyway, Maine hosts whole fleets of migratory species in the spring and fall. Of the roughly 1,000 bird species one might spot in the Lower 48, birders in Maine have identified 462 of them.

And while the richness of Maine’s birding scene derives largely from its geography — and from nationally recognized hotspots like Acadia National Park, Monhegan Island, and Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge — it also owes to its people, to a shared fondness for natural history and a commitment to conservation that extends from the Wabanaki to Thoreau to Rachel Carson to Stephen Kress and the scientists of Project Puffin. It’s quite a flock to join — consider these pages a fledgling’s introduction.

A DILETTANTE'S GUIDE TO THE FINE FEATHERED WORLD OF

By Nick Lund, Brian Kevin, Maggie Nevens, and Willy Blackmore

From our September 2019 issue

If you’ve ever caught your breath to hear a loon call up at camp, if you’ve ever stopped in your tracks to watch an osprey riding high on coastal thermals, if you’ve ever chuckled at a puffin making a crash landing on a grassy island knoll, then you know the experience of birds is inextricable from the experience of Maine. And you know you don’t have to be the kind of person who keeps a life list in order to find joy in the state’s avian abundance.

But among those who do — keep a lifelong, cumulative record of identified bird species, that is, and who travel to expand their lists — Maine is considered a top birding destination. Why? In a word: habitat. The state’s deciduous and transitional forests, its coastal and higher-

elevation boreal forests, and its here-marshy and there-rocky coast all support distinctly different bird populations. And because it sits at the heart of the Atlantic Flyway, Maine hosts whole fleets of migratory species in the spring and fall. Of the roughly 1,000 bird species one might spot in the Lower 48, birders in Maine have identified 462 of them.

And while the richness of Maine’s birding scene derives largely from its geography — and from nationally recognized hotspots like Acadia National Park, Monhegan Island, and Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge — it also owes to its people, to a shared fondness for natural history and a commitment to conservation that extends from the Wabanaki to Thoreau to Rachel Carson to Stephen Kress and the scientists of Project Puffin. It’s quite a flock to join — consider these pages a fledgling’s introduction.

So You Want to Be a Birder

BINOCULARS. Upgrade from that clunky pair of “porro prism” binoculars you’ve had knocking around the house — the ones with the eyepieces and objective lenses offset — and pick up some modern “roof prism” binoculars, which have straight ocular barrels and are lighter and more comfortable to hold. A perfectly serviceable pair runs $100ish, while an excellent pair will run a couple grand (worth it, as they’re better in darker conditions and last a lifetime).

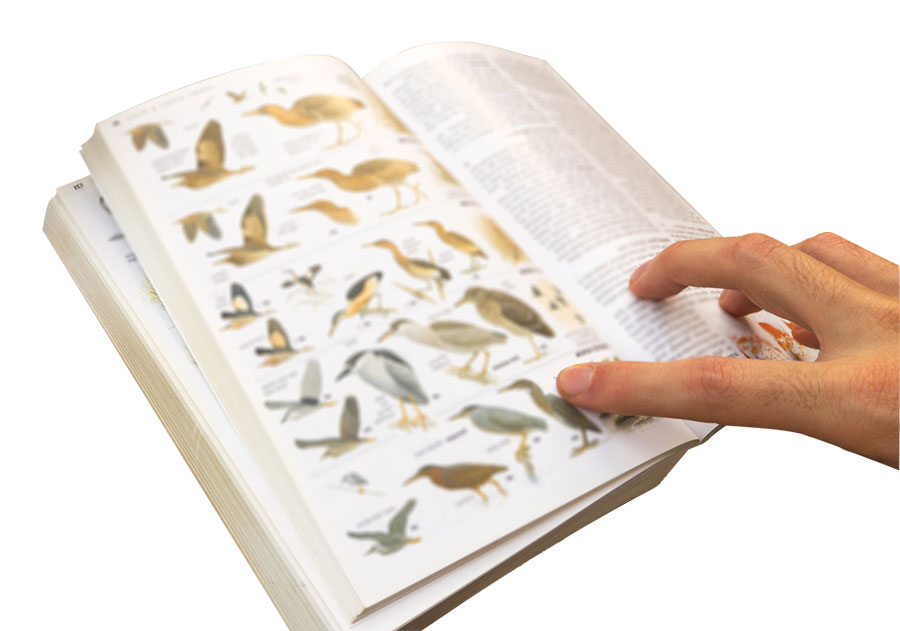

FIELD GUIDE. The term understates how useful this book is: a field guide is a textbook, a treasure map, a reference manual, and a travel agent. My favorite is the classic Sibley Guide to Birds for its thorough but straightforward presentation (there’s a great app too), but some prefer the more dramatically illustrated National Geographic guides. For beginning Maine birders, the free Maine Birding Trail brochure at is essential reading.

FRIENDS. You can start solo and simple, studying the birds in your backyard. Ask yourself, are they migratory, or do they stick around all year? Do the genders look different? Then, join others in the field. Maine Audubon offers weekly Thursday-morning bird walks from their Falmouth headquarters and runs regular trips to state hotspots. Find a calendar at maineaudubon.org/events. — N.L.

FLOCKING TOGETHER

Feathers over Freeport

LATE APRIL

Two jam-packed days of family- and beginner-friendly events in the Freeport-area state parks (all free with park admission). Guided bird walks, mountaintop hawk-watching, art workshops, crafts for kiddos, food trucks, and more. ► Bradbury Mountain and Wolfe’s Neck state parks.

207-688-4712.

Wings, Waves & Woods

MID-MAY

One part birding festival, one part art festival. Naturalist-led trips on land and sea (including for puffin-spotting at Seal Island National Wildlife Refuge), plus exhibits of avian and landscape art. ► Deer Isle and Stonington. 207-348-2455.

Down East Spring Birding Festival

MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND

Four days of guided hikes, boat tours, and demos around Cobscook Bay, among the state’s richest birding grounds. ► Trescott. 207-733-2233.

Acadia Birding Festival

MAY 28–JUNE 1

Maine’s oldest and largest birding fest offers a huge slate of trips on and around Mount Desert Island, from hikes around the national park to paddling and island excursions. Rock-star keynote speakers too. ► Acadia National Park and environs. 207-233-3694.

Rangeley Birding Festival

EARLY JUNE

Just off its first year, this fest, focused largely on boreal species, included guided hikes, loon cruises, birder social hours, and presentation of the John Bicknell Conservation Award for environmental stewardship. ► Rangeley. 207-864-7311.

Maine Audubon offers guided excursions, expert talks, camps, and workshops year-round. Freeport’s Wild Bird Supply leads walks, tours, and events, including its Birds On Tap trips with the Maine Brew Bus. Find more on Maine birding tours and festivals at mainebirdingtrail.com.

BESTof THE NEST

NORTHERN SAW-WHET OWL

Once known as the Acadian owl, Maine’s most common owl species is also its hardest to see. They’re tricky because they’re strictly nocturnal (unlike barred or great horned owls, which are often seen during the day) and because they’re as small as an American robin. The best way to find one is to listen carefully: males call out to females on nights between January and May, a high, constant, and monotone “toot” that sounds (evidently, given the name) like a spinning grindstone — or the world’s most annoying flutist practicing in your backyard.

COMMON EIDER

Mallards get all the love, but common eiders look down their stubby bills at those puddle ducks begging for crumbs in the park and instead dive along our rocky coasts plucking mollusks, crabs, and sea urchins off the seafloor. The Northern Hemisphere’s largest duck, common eiders can be found off the Maine coast all year long, but they’re most noticeable in winter, when they congregate into large rafts floating just offshore. Look for the mix of boldly plumaged black-and-white males and all-brown females, and when you see them, raise a toast (rather than wasting toasted bread on those mallards).

Common eiders were almost hunted to extinction before the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

PIPING PLOVER

Nobody loves hitting the beach as much as piping plovers do. In a rush to claim the best territory, these tiny shorebirds arrive on Maine beaches as early as March, when there’s often still snow. Nesting on the beach brings them close to their invertebrate prey but also into contact with their peskiest bane: us. Habitat loss and human disturbance reduced the state’s population to just seven (!) pairs by 1981, but conservation efforts have returned 87 nesting pairs to Maine, by this year’s count, on sandy beaches from Popham to Ogunquit. There’s even a pair nesting in front of the ferris wheel at Palace Playland in Old Orchard Beach.

BLACK-THROATED GREEN WARBLER

Each spring, millions of colorful songbirds called warblers migrate from Central and South America to breed in the U.S. and Canada. Maine is home to more than 20 species, each with its own bright plumage and unique song, but the black-throated green provides the soundtrack to a Maine summer. Listen for their buzzy song: zee-zee-zee-zoo-zee! Or, as some birders remember it, trees trees, I love trees! A helpful mnemonic, since these warblers hang out high in trees, making it tough to get a look. Try anyway, because their black, yellow, and green plumage is a showstopper.

Male warblers’ loud and persistent singing establishes and defends their territories.

BOREAL CHICKADEE

Everyone knows the black-capped chickadee is the Maine state bird, right? Well, the 1927 statute actually states only that “the state bird shall be the chickadee.” Most Mainers have assumed the title belongs to the black-capped, callously ignoring Maine’s other chickadee. Hearty little brown-headed boreal chickadees live only in northern Maine, and they aren’t as numerous or gregarious as black-caps — although unlike black-caps, they’ve been observed scavenging frozen deer carcasses. Your best shot to see Maine’s “other” state bird is in the dense conifer forests of the Rangeley area

or Baxter State Park.

Boreal chickadees cache bugs and seeds in bark crevices for winter food.

GREAT BLACK-BACKED GULL

Dear anyone who’s had her ice cream stolen off a cone or his car soiled from above: Give gulls another chance, starting with the great black-backed, the world’s largest gull species and the most regal of Maine’s three common gulls (ring-billed and herring gulls being the other two). Unlike their dumpster-diving relatives, great black-backs are almost never seen away from the coast. All the key identification points are there in the name: look for their great size (bigger than most hawks) and their dark-gray back (compared to the silver-colored back of the more common herring gull), then start on the path to forgiveness.

BLACK GUILLEMOT

They may not have the cachet of their famous cousins, Atlantic puffins, but black guillemots have none of their relatives’ diva tendencies either. Puffins are only in Maine for the summer and make you head way out to sea in order to see them. By contrast, you can spot guillemots year-round and from most any rocky coast in Maine. Their tidy summer plumage is all black with bright-white wing patches; in winter, they’re more of a mottled black-and-white. Look for this duck-size bird diving just beyond the breakers, and enjoy the easy company of the “people’s puffin.”

The black guillemot can stay underwater for more than two minutes at a stretch.

SPRUCE GROUSE

One of Maine’s most sought-after species (by birders — there’s no hunting season for spruce grouse) is also one of its toughest to find, largely because you can walk right by one and not know it. These well-camouflaged birds show little fear of humans, which is how they earned the nickname “fool hen.” Luckily for them, their diet of mostly conifer needles means they taste like a Christmas tree. The size of a chicken, they’re at home in dense boreal forests in northern Maine and far Down East. Females are a barred brown-and-white, males a showy black-and-white, with a bright-red comb of skin above their eyes, like fabulous eyelashes. A sight to behold — if you can find them.

Females cluck, but males are mostly quiet, making only an occasional low croaking sound.

PHOTOGRAPHS: SHUTTERSTOCK

On the Origin of Species Spotting

FIVE AVIAN-LOVING MAINERS ON HOW THEY CAUGHT THE BIRDING BUG.

Sarah Violette

AGE: 30

HOME: PORTLAND

OCCUPATION: RAPPER

I went to college at the University of Southern Maine to become a journalist, but I fell in love with music and photography. The professor in my media class basically told me, “It’s cool that you write so much about hip-hop, but try writing about something different.” So I picked bird-watching and wrote a big piece about it, because I didn’t understand how people found a thrill in it. Then I started getting into it. I started keeping my camera in the car with me and started a bird-photo blog. Bird-watching got me through a bad break-up. I used to keep a tally — you know, I saw so many species this year. But I didn’t want to be so obsessed with listing, I just want to keep it pure and about the moment. It’s like making the music versus selling the music — just keep it pure.

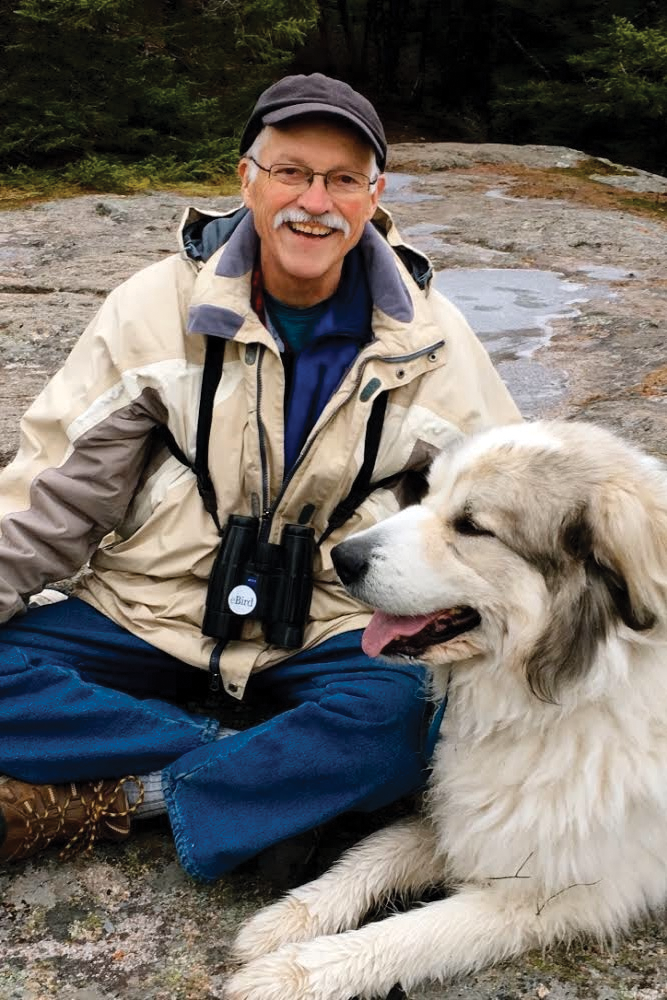

Bernd Heinrich

AGE: 79

HOME: WELD

OCCUPATION: EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT, RESEARCH ASSOCIATE AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE, AUTHOR OF 22 BOOKS, INCLUDING MIND OF THE RAVEN AND WINTER WORLD

Before I was 10 years old, growing up in northern Germany, I was climbing trees and getting birds. I got a crow and had it as a pet, and then after that I had a wild pigeon. So I got to know birds as individuals fairly early. My father, an entomologist and ornithologist, was a great influence because he’d been around the world collecting birds for museums and zoos, so his interest rubbed off. I didn’t have any toys whatsoever in our cabin in the woods, not even a scrap of paper, so my playthings were in nature — not just birds but also insects and almost anything alive. I got very interested in nests. I collected one egg from each species, and I had a little box with, I don’t know, 15 or 20 eggs. I still have that box, actually. I brought it from Germany when we came to Maine, when I was 10, in 1951.

Peter Rudenberg

AGE: 18

HOME: FALMOUTH

OCCUPATION: RISING FRESHMAN AT GETTYSBURG COLLEGE

My earliest memory of intentionally paying attention to a bird is from when I was 5 and lived in Haiti. I looked out the window to see what looked like a burrowing owl sitting on a tree branch right outside the window — I wouldn’t have known the species then; I was just watching it turn its head around. Then, when I was 8, there was a missionary family who came, and the father was an avid birder. He’s who really got me hooked. Because of him, I participated in the first five Christmas bird counts in Haiti — in the town where John James Audubon was born, actually. Four years ago, we moved to Maine, and continuing birding was a no-brainer: just the beauty of birds, the variety — you can go to the next town over, and the song sparrows will sound different. I’m actually hoping to study ornithology. It’s shaped my life quite a bit.

Anna Siegel

AGE: 13

HOME: YARMOUTH

OCCUPATION: RISING EIGHTH GRADER AT FRIENDS SCHOOL OF PORTLAND

In fifth grade, on a family trip to Belize, I found my “spark bird” — that’s the bird that lights the fire for birders and begins a lifelong fascination. It was a rare orange-breasted falcon, only 70 breeding pairs in the world. As soon as we got home, I dug binoculars out of the basement and found an old bird book at my grandparents’ house. That was the first time I realized birding was a thing. I was fascinated with flight and mechanics, and my grandma brought me to my first birding mentor, at Freeport Wild Bird Supply. Birding just became a way to go out into the world and experience how special birds are and their relationship to humans is. Since fifth grade, I’ve been a member of the Maine Young Birders Club, and it’s how I’ve met friends from all over the state. My passion for conservation and birding has led me to studying how the climate crisis is impacting bird diversity and what devastating consequences will follow.

Doug Hitchcox

AGE: 30

HOME: WINDHAM

OCCUPATION: STAFF NATURALIST AT MAINE AUDUBON

I was 16 when I got my first car, a crappy Honda Civic that I thought was the greatest car in the world. I went online to Honda-owner forums where people posted photos of their cars, and I said, I wish I could take photos like that. So I ended up buying this camera, and I took pictures of everything around my parents’ yard. And there was a bird, what I ultimately figured out was a chipping sparrow, that I crept up on and got a decent photo of. I looked it up in an old Audubon field guide, and being able to label the photo, there was this parallel with how I’d always been into collecting things. I had coins, stamps, rocks, Pogs. I was just the right age when Pokémon cards blew up. So birding was kind of the ultimate collection. In the Pokémon video game, you traveled around to these different habitats and found different monsters. You could say that birding is just like real-world Pokémon.

As told to Brian Kevin and Maggie Nevens, edited for length and clarity.

Portraits by Christine Mitchell Adams, original photos by Allie Conn (Violette), Kevin Blanc (Heinrich), Meghan Wakefield (Rudenberg), Fred Field (Anna Siegel), courtesy of Maine Audubon (Hitchcox)

The Greatest

When a wildly out-of-range great black hawk showed up last winter, the saga of the one-in-a-million vagrant raptor stole (and broke) many Mainers’ hearts.

Christine O’Leary Murphy (of Woodbury, Connecticut): We’ve been going to Maine for 42 years on vacation, to Biddeford Pool. I walk Fortunes Rocks Beach every morning, and I always have my camera. He flew right over me and landed in a branch 5 feet away. I took a lot of pictures, and I’m surprised they came out clear, because my hand was shaking. When I went through the pictures that afternoon, I thought, I can’t figure out what he is.

From Instagram, 8/6

@cmmurphy56: Can someone tell me what kind of hawk this is?

@rdub5000: Location?

@cmmurphy56: Maine

@rdub5000: I’m stumped. This looks like a common black hawk, but it’s WAYYY out of range.

@nickhaw: Where exactly in Maine Christine? I think like every birder within 24 hours of driving will want to come search for this bird.

Doug Hitchcox (staff naturalist, Maine Audubon): The American Birding Association has a Facebook page called What’s This Bird? It was posted there, and that’s where it got identified as a great black hawk. Word got out pretty quickly.

From Instagram, 8/7

@neogonzo: On Facebook, this bird was debated over by some of the top birding minds in America, who seem to conclude it was indeed a great black hawk, a species that has almost never been seen in the U.S. It’s so rare that it’s hard to believe it is what it is and especially where. I am sure there are dozens of people looking for it as we speak!

Hitchcox: I went out to Fortunes Rocks the second morning, with tons of birders, and we couldn’t find it. That’s like the ultimate punch in the gut to me, so I spent the day at my desk, cringing, looking at photos of it. I went back that afternoon and finally found a bunch of robins freaking out because it was raiding their nest. It was only seen for one more day after that, because hundreds of people showed up that next day and ultimately scared it away. It was kind of a mob scene.

Murphy: Did you know people took the red-eye in? Flew from California! My husband was driving out of Fortunes Rocks and said, “Christine, you’ve caused chaos here. There are cars all over!” I thought, oh god, the neighbors are going to kill me. It was the birders who ended up chasing him away. I went out every day after and couldn’t find him. Part of me thought, good — nobody will chase you wherever you are.

Hitchcox: There was a sighting at [Portland’s] Eastern Prom at the end of October, and that kind of made everyone freak out that it was still around. Then, it wasn’t until the end of November that it showed up in Deering Oaks park.

Anne Pringle (president, Friends of Deering Oaks): I first saw it when I was just driving by the park one day. I saw a lot of people gathered and thought, what is going on? The bird was on the ground, feeding on a squirrel. After that, every time I went anywhere near the park, whenever I saw people assembled, I stopped. And I’m not a birder, but I could really appreciate this bird, because you could see it close up. It was just really a beautiful bird, and it seemed totally untroubled by all the people, all the traffic.

Diane Davison (former chair of the Portland Parks Commission, board member and volunteer at Avian Haven bird rescue): There were people who flew across the country that keep a life list and people who were just curious who don’t even go birding, who just went to see this unique creature. People spent hours.

Pringle: I would say, where are you from, where are you from? “Westbrook.” “Northern Maine.” “Michigan.” “Texas.” One guy had been here for a business meeting and heard about the bird, and he extended his stay in Portland just to stick around and see it.

From Twitter 11/30–1/4

@devon_beland: I saw the Great Black Hawk that’s in Portland on my lunch break today, and let me tell you, this bird was an absolute unit. At least 35+ people following this bird from tree to tree with tripods and such.

@MisterBQbirds: GREAT BLACK HAWK, one of the rarest birds and furthest chases I’ve ever done. To Maine [from Philadelphia] and back for a MEGA rarity!

@nickkauf: What Maine name should we give the #greatblackhawk in honor of its visit to our great @CityPortland? @mayorstrim will u give it key to the city?

Hitchcox: It’s a large, charismatic species. And this was a funny bird: it would just sit in the same tree for hours at a time, maybe move once or twice throughout the day to catch a rat or squirrels. So anyone walking through the park who saw this large gathering of people could say, “What are you guys looking at?” And you could point and say, “That bird, right there.”

Pringle: This bird was named the Craziest Vagrant of 2018 by the American Birding Association. When somebody from Maine Audubon gave a talk here recently, he said, “Seeing this bird at Deering Oaks would be like seeing a zebra at Baxter State Park.”

Murphy: My brother is texting me, “Christine, your hawk is on the NBC News.” I was keeping tabs through a friend up in Maine who sent me news clippings. I prayed to god that people wouldn’t go and scare him. And then I think he just wasn’t equipped for the winter.

Pringle: Some people wanted to see it captured and stored over the winter, then re-located.

Hitchcox: If you were to catch and ship it back to — we don’t even know where it came from — anytime you relocate animals, their survival rate is incredibly low. So I think it would be have been a faster death sentence if it was relocated.

From the Facebook page of the nonprofit bird rehab center Avian Haven, in Freedom, 1/20

The Great Black Hawk who has been hanging out at Deering Oaks Park in Portland for the past few months was found on the ground today. The roads were treacherous, but an undaunted team of volunteer transporters helped get the bird safely to Freedom. The hawk arrived here around 5 p.m. and is now settled into an intensive care unit for the night.

Davison: A woman who lives in the West End went cross-country skiing in a blizzard to see if the bird was around and found it pretty well frozen on the ground.

Diane Winn (avian rehabilitator, cofounder of Avian Haven): I took the call. It came from a woman named Terra Fletcher. If I remember correctly, she had come upon a gentleman [Alfredo Nicolas, of Portland] kneeling in the snow, trying to help the hawk. She knew right away it was the great black hawk. Terra had sent photos of the feet — she had already recognized signs of frostbite on the toes.

Davison: I got the call from Avian Haven that the bird was down, so I got in the car and drove with my flashers in this ridiculous weather, scooped up the bird from Terra, and brought it home. Of course, frostbite was the biggest concern, and I started gently trying to warm the bird up with heating pads and prepare it for transport. The bird was quite frozen. The only way I could tell it wasn’t gone was if I gently slipped my hand under its head, it would respond a little bit.

Winn: After that, the conversations were all about who was going to travel in the sleet storm. I contacted warden Josh Tibbetts. He was going to get the bird from Diane and drive north, but in the process of attempting to rescue a different bird, he slipped on icy stairs and was injured. He went to the ER. So it was up to our volunteer transport team.

Davison: It usually takes an hour-and-a-half from Portland to Avian Haven, and I think, total, it took almost 4 hours. I drove with another volunteer to Topsham going 35 miles an hour, and when we handed him over, his eyes opened, and we were feeling so hopeful.

Winn: Initially, we were cautiously optimistic. We knew that the progression of frostbite is unpredictable and insidious but had no way of knowing how far things had already gone by the time the bird was rescued. We pulled out all the proverbial stops in treating the feet that evening and thought, “If this is as bad as it gets, he should pull through.”

From the more than 500 Facebook comments Avian Haven received during the hawk’s first 48 hours at the center.

Tracy Johnson: I have been thinking of this poor bird as the cold set in! I am so glad to hear he is safe with you! I pray he can recover!

Merrilee Levensailor: Love the poor baby!!!

Nina Houghton: Thank you, thank you, thank you! You are angels on earth!

Annie McLachlan Bourke: If this bird makes a full recovery what will become of it since it cannot be released?

Mark Deschesne: Are you going to return it to it’s natural environment??

Johanna Gilman: What is he/she being fed?

Winn: It was immediately obvious that inquiries had the potential to swamp us. Any people who called, whether they were media or private citizens, were told that we had nothing to say beyond what was on our Facebook page. We still got treatment advice, requests for updates and to visit (one caller even asked how much it would cost to get in), but it was nothing like the volume on Facebook. Also, we worked very closely on this with the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, and they agreed that all communication would come from us via Facebook. Of course, people still asked them questions. In fact, I think the first question asked of new commissioner Judy Camuso at her confirmation hearing was about the hawk.

Things looked a little worse every time we examined the feet and legs, but until about a week in, we still thought there might be some hope. Things deteriorated markedly in the two to three days after that.

From Avian Haven’s Facebook page, 1/31

Our treatment efforts followed the most up-to-date protocols in human and veterinary medicine. Sadly, however, because foot and leg tissues had already been irreparably damaged, those efforts came too late. . . . The decision to euthanize was completely unanimous among all who gathered here yesterday, though that decision was tinged with regret, sorrow, even heartbreak.

Winn: The procedure for euthanizing a bird is the same as for any other animal euthanized by a veterinarian — anesthesia followed by injection.

From the 1,324 comments left in response to Avian Haven’s announcement

Heidi Flewelling: I am so sad to read this — it was very difficult seeing through my tears.

Nancy Markey Gleason: My heart aches for this magnificent hawk and for all who worked with enormous intelligence and heart to save him.

From “The Great Black Hawk,” a poem by Michael Rafkin, posted on the Instagram page @greatblackhawkmaine, 5/20

I cannot stop my weeping / though you still fly in my mind / I’ll never know why you chose the snow / leaving paradise behind.

Davison: It’s always upsetting when you do the best you can and then they don’t survive, but with the great black hawk, it was pretty intense that he didn’t make it. So many people cared. I like to think of all the people walking through the park who maybe weren’t looking up before and noticing the native birds, that now maybe they’re a little more aware.

Murphy: I was sad. Now, I have a huge 11×14 print of him on my refrigerator. He’s right here. I see him every day.

Pringle: I still drive by the park and look for it like it’s going to be there. But of course, it isn’t.

Friends of Deering Oaks is raising $29,000 for a statue and interpretive display to be installed by next spring. For more info, visit deeringoaks.org. Avian Haven gave the great black hawk’s remains to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. The bird has been mounted and will display at the Maine State Museum.

NO SLEEP

PORTLAND

THE BIGGEST DAY in Maine birding history began at midnight on May 30, 2011, at the edge of a sedge meadow someplace in Aroostook County. Bill Sheehan, of Caribou — part of a four-man team that included friends Lysle Brinker, Robby Lambert, and David Ladd — thought the meadow might hold a rare yellow rail, a tiny and notoriously shy marsh bird. In the darkness, the four men strained their ears, listening for the bird’s metallic-click song. Nothing. After a few minutes, as badly as they wanted to keep listening, they couldn’t afford to wait. They piled into a rented SUV and charged off into the night. The clock is always ticking on a Big Day.

Competitive birding relies on the honor system and traces its roots to a footnote in Roger Tory Peterson’s 1955 book Wild America, which chronicled a 30,000-mile birding adventure undertaken by the author and a friend. It read, “My year’s list at the end of 1953 was 572 species.” Some birders viewed that number as a challenge and set out to beat it — or to set records for bird species seen in a calendar year (called a Big Year) or single day (a Big Day) within their country, state, or county.

Big Year attempts favor the birder with free time, the young and/or underemployed who can drop everything and chase a rare bird on a moment’s notice (Maine’s current Big Year record of 317 species was set in 2017 by then-34-year-old Josh Fecteau, of Kennebunk). Big Days, meanwhile, favor the planner, with hopefuls aiming to reach as many different habitats over the course of a day as allowed by travel times, traffic and bird-activity patterns, tides, and weather — to say nothing of the time swallowed up by actually locating and correctly identifying each species.

None of these obstacles intimidated the team in the Aroostook County sedge field. They’d done this before. Sheehan, Ladd, and Brinker had met years before on the Maine birding scene and jointly set several Maine Big Day records in the 1990s, eventually notching a record many considered unbeatable: 178 species on a single day in 1999.

It stayed unbeaten for 12 years. Then, in mid-May 2011, a team consisting of Maine Audubon naturalist Eric Hynes, his brother Casey Hynes, Todd Day, Bill Hancock, and Luke Seitz (a teenage “upstart punk” in Sheehan’s affectionate words) spotted 183 species. That record wouldn’t stand for long, as Sheehan’s team was already prepping for their attempt — and they had a trick up their sleeves.

The biggest limiting factor in a Maine Big Day is distance. Most attempts are made in May, during the short window when birds that spend winters down south have returned to breed, but before all the birds that winter in Maine have left. Even then, some birds that migrate north can only reliably be found in Maine’s Aroostook County. Of course, losing five hours on the highway between The County and southern Maine sounds the death-knell for a Big Day attempt, so most attempts skip The County and instead begin in the high-elevation Rangeley area.

But Ladd, it happened, had a neighbor in Oakland, Zlatko Necevski, who was an airplane pilot. If they could start in Aroostook, then quickly fly south, the team figured they could potentially notch several more species. And while air travel is basically unheard of for state attempts, it’s perfectly acceptable under American Birding Association guidelines. Necevski was game — he could visit family in The County — and the plan was set.

The team’s luck improved after missing that yellow rail. Sheehan, the only team member who lived in Aroostook, led the crew to all his regular haunts: Lake Josephine, Lake Christina, Burnt Landing Road. The birding was good, and the group identified more than 100 species, including an elusive American three-toed woodpecker and a spruce grouse, before heading to the Presque Isle airport just shy of 8 a.m.

They’d been up all night, but no one slept on the 175-mile flight to Waterville. “We were too jacked up,” Brinker recalls. In a car they’d left waiting at the airport, they hurried to the freshwater marshes near Belgrade (for black tern and pied-billed grebe), then headed south.

The afternoon was a grueling ping-pong among sites in southern Maine, the team all but leaping out of the car to spot target species, then hurrying back in. A lingering fog hindered visibility along the coast, but they scored a roseate tern at Pine Point in Scarborough, a red knot at Biddeford Pool, and a red-bellied woodpecker on a nest in South Portland. In all, the team covered 560 miles by car.

By evening, the tally was going well, but fatigue was setting in, and new species were popping up less often. Still, the team pushed on, arriving at dusk at Kennebunk Plains, a rare-for-Maine sandplain grassland ecosystem, where they quickly tallied upland sandpipers and clay-colored and vesper sparrows. It was in Kennebunk that the group realized they’d beaten the record. They did not stop to celebrate.

The crew kept birding into the night, listening for owls and other nocturnal birds. Somewhere in Portland, Sheehan remembers “waking up in a pile of drool to David saying, ‘C’mon, we’re listening for owls!’” They ticked great horned and barred owls and a whip-poor-will before calling it quits just before midnight. The final tally: 187 species.

More than eight years later, the record still stands. And while Maine birders now recognize the superior route between Aroostook and southern Maine, the complexity and cost of chartering flights has kept other birders at bay. Still, the record is not unbeatable: the team missed several species they might have found on their record-setting day — white-breasted nuthatches, laughing gulls, a number of seabirds — and if another group were to try, they might just be luckier.

It’s a challenge the record-setting team would welcome. “I’d love it if others would attempt a Big Day,” Brinker says, “because I’d love to try to win it back again.” — N.L.

AN UNFINISHED PROJECT

After Peter Vickery was diagnosed with stage-four esophageal cancer in 2015, he had a particular means of asking his doctor about the prognosis. “Peter’s way of asking the question was to explain, ‘I’ve got this book I’m trying to finish,’” recalls Barbara Vickery, who was married to the much-admired Maine ornithologist for 47 years.

The book Peter had in mind — a project he’d been working on in some fashion nearly 40 years — was an exhaustive update to Maine Birds, a doorstop of a 1949 text, written by Maine biologist Ralph Palmer. Still considered a classic, Palmer’s book thoroughly documents every species of bird then known to have lived in or visited Maine. By the time of his diagnosis, Peter had written three-quarters of the species entries for his book, to be titled Birds of Maine, and had a trove of data on the state’s avian life — including 100 species newly documented in Maine since ’49. And by the time he lost his cancer battle in 2017, he’d assembled a team of leading bird experts — all of them friends and colleagues — charged with completing his life’s work.

“He had always wanted to make this a world-class book, the way Palmer’s was,” says Jeff Wells, of Gardiner, vice president of boreal conservation at the National Audubon Society. Wells, who led trips and conducted research with Peter, is one of five co-authors now working to complete Birds of Maine, which Princeton University Press and the Nuttall Ornithological Club will copublish next year.

After 33 years at the Maine chapter of the Nature Conservancy, Barbara is now managing the book project nearly full-time, and she’s become more of a birder than ever. The work, and Peter’s voice within it, has been a boon in a difficult time. “For me, personally, it’s been a gift, because the book team really needed me — the book needed me,” she says. “And I needed the book.” — W.B.