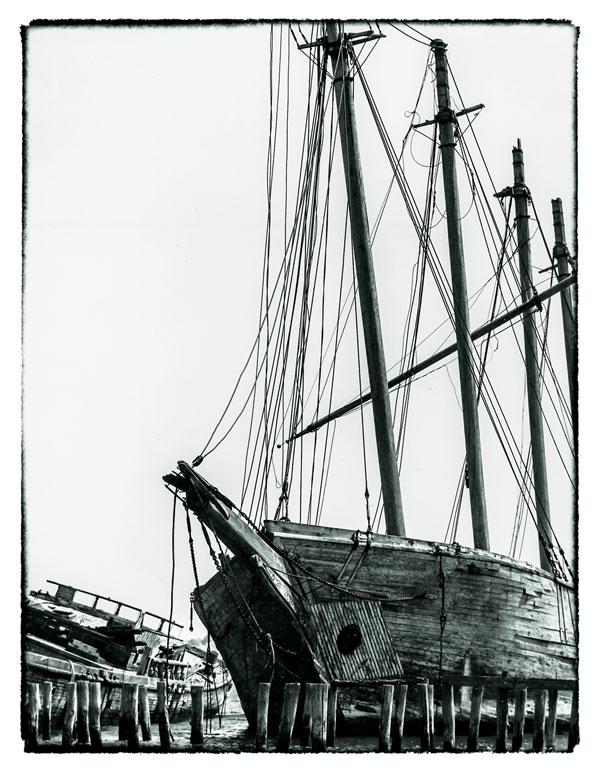

Wood from Wiscasset’s famous grounded schooners lends richness and character to a custom kitchen.

By Meadow Rue Merrill

Photographed by Dave Cleaveland

From our May 2013 issue

Once among the most photographed ships in the world, the Hesper and Luther Little hauled coal and wood and ice before winding up in Wiscasset. There, the four-masted schooners floundered for nearly seven decades, rotting beside Route 1 in the Sheepscot River before being removed in the late nineties. Most of the wood — nearly three hundred dump truck loads — went to a landfill. But the Luther Little’s towering Douglas fir masts lay in a local junkyard, nearly forgotten until a family tragedy gave them new life.

“Your sister’s house is on fire!” the caller told Cheryl Thayer on that fateful September day a little more than two years ago. The Wiscasset native hung up her cell phone and rushed home from shopping only to discover the blaze wasn’t at her sister’s place, next door. It was at hers.

The snug ranch where she and her husband, Bill, had lived for twenty-two years burned to the ground. Little more than their log bed could be saved. Firefighters blamed a laptop computer left to charge on a couch. The power cord had somehow sent out a spark, igniting the cushions. As a result, the Thayers, their two teenaged children, and Cheryl’s fifty-year-old brother, who is disabled and lives with them, were homeless.

Both Cheryl and Bill had grown up in Wiscasset and worked for the town — she for a few years with the school department, he for three decades running equipment for the highway department and plowing roads. While they waited to rebuild, the townspeople kept them afloat, holding fundraisers and donating food, clothing, money, and gift cards.

“It’s hard to believe the support that came from this town,” says Bill, a large man with a friendly manner.

“We were just amazed,” Cheryl adds.

While renting in Wiscasset, the Thayers hired Hammond Lumber Company to design their new 2,000-square-foot home, an expansive ranch with an open floor plan, pine floors, and vaulted tongue-and-groove pine ceilings.

One day, the former town road commissioner, Bob Blagden, suggested Bill look at some wood behind his Route 27 auto garage. A decade after being removed from the harbor, three of the Luther Little’s masts were languishing under a tarp. Blagden had rescued the masts from a Dresden craftsman who had planned to make plaques for the town in exchange for the wood, but went bankrupt before he could complete the project. Another Dresden builder, Paul Ruff, bought some of the masts for a kitchen he was building in Massachusetts. The rest remained unused.

For $2,000 the Thayers bought enough wood for their entire kitchen. Blagden, who owns a sawmill, cut the mast sections into quarter-sawn planks for a nice, straight grain. To build the kitchen, the Thayers hired local cabinetmaker David Eddy, of Knox Eddy Builders, and William Miller, of Auburn.“I remembered those schooners lying in the river from years ago,” says Miller. “They were quite a landmark, so when I heard they were able to salvage the masts and that was what we were going to use, I was very interested. The day they showed me the wood, I was just amazed at what good shape it was in.”

Miller drew the design with Eddy and Cheryl, selecting flat-panel cabinets with a slightly larger, grooved bottom rail and curved top molding to give the kitchen a nautical feel. Working with the wood was challenging. “Douglas fir tends to be splintery,” Eddy explains. “But this seemed to be a little more stable. The biggest difference was the growth rings. It was just such a straight, tight grain that you knew it was old wood. You just don’t find that anymore.”

While the masts were weathered from a century exposed to the elements — and had survived several fires of their own — the interior wood had a color depth and richness Eddy had never seen before. To accentuate it, he and Miller finished the cabinets with a natural oil and varnish mix. “I’m just amazed something that old looks that good,” Bill says. “I never would’ve believed we’d have them in our kitchen.”

Fittingly, the masts’ final resting place is just three miles from the harbor where the ship once lay rotting. The honey-colored cabinets create a generous galley with an eleven-foot raised bar with an oak countertop and room for five upholstered stools. Black marble countertops, from All in One Mill Work in North Windham, sparkle under the glow of hanging onion lanterns. Purchased from 17-90 Lighting in Rockland, the rustic lights resemble those once used on fishing schooners. The stainless-steel stove has a backsplash of natural stone tiles, arranged by Cheryl, and a weather-beaten strip of ship’s mast edges the wood-paneled ventilation hood.

“The Luther Little Kitchen,” Cheryl calls it, adding that she plans to hang a picture of the ship on the burgundy-painted wall above a doorway leading down the back hall.

While the open living room with its oversized leather sofas and the adjoining sun room with an indoor water fountain and cozy woodstove welcome guests, the kitchen is definitely the gathering place. “We like to entertain,” Cheryl says. “So I wanted lots of room to cook for friends and family.”

Unused wood from the masts trims the sunroom windows and forms an entertainment bar, built by local carpenter Craig Johnson, on the back deck. The Thayers’ daughter, Chelsey, a sophomore at Wiscasset High School, took the leftover wood to school, where she is building a coffee table.

The Thayers are still astonished to have a permanent piece of town history in their house, which after a year they say is beginning to feel like home. “I guess it is a happy ending,” Cheryl says. “Something good came out of something really bad.”