By Bridget M. Burns

From our July 2022 issue

Soon after I moved to Kennebunkport, in 2009, I got a job working at Wink’s, a mom-and-pop sandwich shop. The store opened at 5 a.m., which made it the preferred morning hangout for the town’s lobstermen, many of whom arrived early to chew the fat while Jenn, the owner, finished brewing the coffee. When I first showed up behind the counter, they were curious about the new girl in town. But when they found out where I lived, they often had more stories for me than I had for them.

“Ah, the Brennon place,” they said, before launching into some tale about their relationship to the house.

It’s a New England convention for houses to keep the name of those who either built them or lived there the longest. But while my home might be “the Brennon place,” it’s part of a longer history. The Brennon house is really an apartment inside of a former cow barn. If the original home was still standing, the property might be called “the Milliken place.” Before my land had only a barn on it, there was a classic connected farmhouse. And before the Brennons, the property was a church-run refuge for Eastern Europeans displaced by World War II.

I knew none of this when I first toured the home, mostly attracted to the building’s age and quirks. I grew up in a colonial-era Saltbox that helped instill in me an appreciation for anything old with a story. My engagement ring was my great-grandmother’s. My dining-room chandelier once hung in my grandma’s house. I built my writing desk out of a door from my childhood home. I had always wanted to live in something that used to be something else, and in my 20s, I was blissfully naive about the costs inherent in living in a drafty, leaking, 130-year-old building. What others saw as ramshackle, I saw as rustic. When I learned the reason for the sign on the barn that read “Freedom Farm,” I found even more story than I’d hoped for.

In 1947, a particularly warm spring led to early snowmelt. An especially dry summer followed, and by autumn, a catastrophic string of fires had broken out across midcoast and southern Maine. The summer colonies of Goose Rocks Beach and Fortune’s Rocks were almost completely destroyed, and only a change in the winds and a bulldozed firebreak spared Kennebunkport’s village center. The town of Kennebunkport encompasses fewer than 50 square miles. At one point, the local fire burned across an 8-mile front.

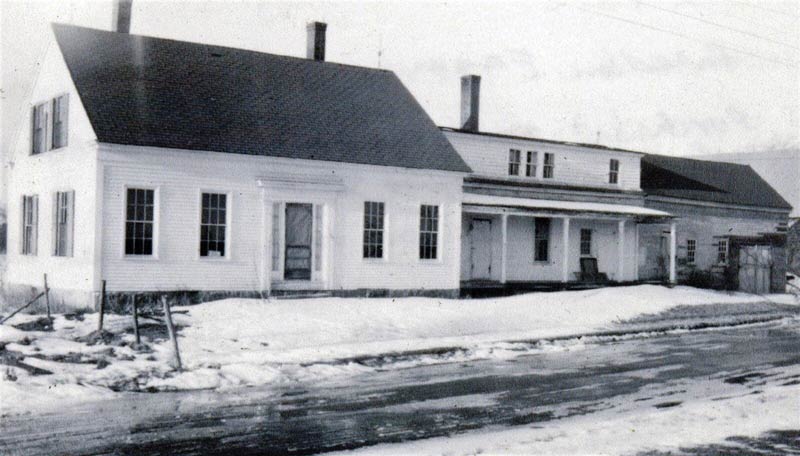

Just a few miles inland, farmers worked together to save their homes and livelihoods. Among them was Ethar Milliken, a dairy farmer who owned two farmsteads on what’s now called Arundel Road. He and his wife, Vera, lived on one, where they ran an active dairy; on the other, the farmhouse he’d grown up in was now vacant. He and Vera hoped to one day expand their herd and revive the second property. As the fire approached, they only hoped to save it.

The flames came so close, they scorched the corners of the barn. A shift in wind spared Milliken’s childhood home, but the firefighting effort cost him his health. He collapsed from a heart attack, was carried home, and spent the better part of the next year recovering.

While bed-bound, Milliken read articles by prominent Portland pastor Reverend Harold Bonell. As a representative of the American Baptist Convention, Bonell had traveled to Eastern Europe after the war, to help interview refugees applying for admission to the U.S. as “displaced persons,” or DPs. He wrote updates for the Maine Baptist Messenger and other church publications detailing conditions in the refugee camps. One Bonell article, from January 1948, showed photos of cramped living spaces, children with no room to play.

With more than 200 of Kennebunkport’s homes destroyed, Milliken felt profound gratitude that both of his farms were unharmed. As historian Walter L. Cook wrote in a 1954 chronicle of Maine’s Baptists, “He saw something he had missed before — how much he owed to God. Full of gratitude, he began casting about in his mind in search of ways to serve Him.”

Milliken knew that even if he recovered, he would be unable to work at the pace he once had. So he and Vera gave up plans to expand their herd. Instead, Milliken sought a religious organization that could use his old homestead to help those in need. In 1948, he presented the potential gift to Charles Ellis, a pastor at Kennebunkport’s Village Baptist Church. Ellis brought the offer to the United Baptist Convention of Maine, which proposed a refuge for DPs. Its board convened and, as Bonell wrote, “it was received with gratitude.”

The farm comprised 156 acres, with 50 for gardening and grazing and the rest capable of yielding 60 tons of hay each year, the sale of which would help provide for the farm’s residents. As a 1948 Portland Press Herald story put it, the church wanted to create a place for refugees to “get their bearings in a new land, to gain a working knowledge of the language, laws, customs, and lifestyle. A place to get used to being free.” When the DPs were ready, the church would help them find more permanent homes.

The 11-room house was old and in need of repair. “Soon,” Cook writes, “Baptists around Kennebunkport were as busy as a ladies’ aid serving a baked-bean supper.” The volunteers transformed the house into three separate apartments with a shared kitchen. Milliken provided a flock of hens, the Baptist Youth Fellowship in Farmington Falls gifted a Jersey cow named Kate (pronounced kah-tee), and young people gathered money for a pair of farm horses named Chubb and Kitty.

The church made a public appeal for couches, window shades, table lamps, tea kettles, and other household items. A Portland seed company contributed seeds, and other farmers pitched in used equipment. On Mother’s Day, a canned-goods drive stocked the farm’s kitchen. It was a huge effort in a tiny town, but Ethar and Vera knew the almsgiving was invaluable. “If only one person is brought out of the rubble of Europe into a new way of life,” they told Bonell, “it will be worthwhile.”

The first family arrived at Freedom Farm in June 1949. Agnes and Ants Parna and their daughter, Lembi, fled their home in Estonia when the Soviets invaded in 1944. They eventually landed in a German prison camp in Austria but escaped and spent a month hiding in the Alps. When they realized the camp was moving west, fleeing the Soviet army, they fled again, to Germany. Eventually, they found refuge at a German farm before being brought to an American-run refugee camp at the end of the war.

American Baptist missionaries and aid workers interviewed DPs in the camps, arranging sponsorship and housing at sites like Freedom Farm for those eligible for resettlement. The Parnas became Freedom Farm’s inaugural residents because a former pastor in Estonia had a seminary friend in Maine. When they arrived, 10-year-old Lembi’s eyesight was nearly lost to malnutrition. Reverend Bonell had been recruited to manage the program his writing had inspired, and he brought her to a specialist in Boston, who recommended she drink milk to reverse what seemed to be the result of a calcium deficiency.

A month after the Parnas’ arrival, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, the United Baptist Convention of Maine held a dedication service in the cow barn that’s now my home. They opened both doors, stocked the loft with hay, and filled the downstairs with chairs. There, they prayed and blessed the farm and its new purpose with a verse from the book of Matthew. “For I was an hungred, ye gave me meat: When I was thirsty, ye gave me drink: When I was a stranger, ye took me in: Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.”

Years later, Florence Pratt, one of the pastor’s daughters, recalled hearing the verse as she worshiped and breathed in the smell of hay. “The tears came to my eyes then,” she told historian Joyce Butler, “and every time that I hear that passage, I think of Freedom Farm. It’s so very apt.”

Florence’s sister, Carolyn, spent the summer tutoring Lembi. By fall, Lembi was ready to enter fourth grade, and midway through the year, she advanced to fifth. Her eyesight recovered, and by the following summer, Carolyn noted that she’d grown six inches.

In the months and years that followed, five more families arrived, along with six single men, all of them from Russian, Estonia, Poland, or Ukraine. They stayed anywhere from six weeks to a year. Some worked at a sawmill in addition to helping to maintain the farm. The DPs hayed the fields, and they milked cows and kept laying hens and vegetable gardens to supplement groceries. The kids had the run of the farm, bringing homemade poles to the Batson River to catch trout for dinner. Neighbors came by often with gifts of toys. Whenever a new arrival was announced, people in Kennebunkport raided their attics for clothes and other essentials to stock the next family.

Ethar Milliken visited the DPs daily, and he picked them up every Sunday morning in his wood-paneled beach wagon to drive them downtown to the Village Baptist Church. Parishioners there stocked the pews with Russian Bibles and did their best to make the refugees feel welcome. “When they first came, because they’d been in concentration camps and under Russian control, they didn’t dare to even smile to show that they were pleased,” Carolyn Pratt told Butler. “They’d come to church stony faced as they could be. But we’d shake hands and smile, and after about a month, they’d begin to smile a little bit.”

In the summer of 2015, my husband, Kevin, and I listed our barn home on VRBO with plans to spend a few weeks at a friend’s place in Portland. A woman named Dee wrote to me, explaining that she and her husband needed a place to stay for the month of June while they waited on construction of their new home nearby. “By the way,” her message concluded, “my husband was one of the original refugees to live at Freedom Farm!”

I got goose bumps at the thought of meeting one of the DPs who’d lived on our property. We hadn’t planned to move out until July, but we hastily made other plans in order to welcome Zbig Kurlanski back to his first American home.

I was nervous when Zbig and Dee pulled into our driveway one evening that spring, but Zbig’s big smile, easy laugh, and grandfatherly mustache put me at ease. We expected we’d give the couple a quick tour, to make sure our renovated barn would meet their needs, but we soon found ourselves gathered around our dining-room table with four tall beers, discussing everything from Zbig’s memories of the farm to upcoming travel plans.

Zbig’s family arrived in the U.S. in September 1951 and lived at Freedom Farm for six months. His mother, Pauline Kurlanska (Zbig later changed his surname to the traditional Polish spelling), had studied nursing, and she was 18 years old, working in a field hospital in western Siberia, when she was captured by the Germans.

Pauline was first sent to Auschwitz, where she was spared the gas chamber and selected for slave labor, then to Dachau, where she was eventually liberated by American forces. From there, she was sent to a string of American-controlled refugee camps, where she gave birth to her three sons: Eduard, Zbigniew, and Bogdan. At first, she hoped to repatriate to Russia, but she heard stories about trains full of arriving refugees being machine-gunned there, so she instead applied to come to the U.S. She told resettlement aid workers that her children’s father had left. When immigration authorities confirmed he wished to waive his parental rights and return to his native Poland, Pauline was allowed to emigrate as a single mother.

Zbig was four when he came to Freedom Farm, his younger brother Bog just two. The oldest brother, Ed, was five and would celebrate his sixth birthday during their stay. He was the only one enrolled in school and perfected his English quickly, though his younger brothers weren’t far behind. Worried about being mistaken for Communists, Pauline encouraged her sons’ Americanization. “I was speaking German, Russian, and Polish along with English when I got here, and obviously English became predominant,” Zbig later told me. “My mother spoke to us in her broken English and refused when we asked, ‘Can we speak some Russian?’ ‘No, speak English!’”

In time, I got to know my neighbor Zbig, meeting with him and Ed to hear what they remembered about Freedom Farm. Though they were young, all three brothers say they still have memories of their first home in Maine: breathing in the smell of the cow barn, throwing buckets of swill to the pigs, visiting the chicken coop across the street. They also remember their weekly rides in Milliken’s car. Their initial trip from New York City to Kennebunkport was only the first or second time the boys had ever been in an automobile. At Freedom Farm, they rode in one weekly, a more memorable event than the Sunday services they arrived at. What has stayed with Zbig is the sound the car made crossing a wooden bridge over the Batson River. “Every time we drove over, it would rattle like crazy,” he says.

The Kurlanska family moved from Freedom Farm to Saco, where the Baptist church continued to offer assistance until Pauline found work as a nurse’s aide at a hospital in neighboring Biddeford. A few years later, she married a Polish machinist named Leon.

Zbig went on to become a lawyer, Ed a nurse, and Bogdan a public-school teacher. Now retired, all three still live in Maine. Zbig, in his mid-70s, shouts a hearty hello whenever he rides his bike past our home. Pauline stayed in Maine until her death, in 2014. According to her children, she often talked about how welcoming and helpful the people involved in Freedom Farm had been. “My mother, I think, found in that experience what she needed to further herself,” Ed says. “It certainly was a stepping stone for us and gave us the opportunity to really excel.”

In the ’50s, government aid for DP resettlement dried up, and Freedom Farm hosted its final refugees in 1955. The Baptists turned the property into a residence for a retired minister and his family. In 1957, Milliken died at home, at age 65, and was laid to rest in the Arundel cemetery, two miles down the road from Freedom Farm. The Kurlanska family stayed in touch with him right up until his passing, visiting him in Kennebunkport and hosting him at their home in Saco. His donation had helped welcome 28 Eastern European refugees to their new life in America.

With Milliken gone and the DP program ended, the property increasingly became more of a burden than blessing for the Baptists. In 1963, the church sold it into private ownership, and in 1968, the farmhouse caught fire when a furnace fan belt malfunctioned. Bob Davis, the owner at the time, was killed in the fire. Eventually, firefighters did a controlled burn of what was left of the house and back buildings, saving only the barn for future use. “The barn was worth more than the house,” one of them later told me. “Especially a barn like that, with a hay loft and of that size.”

The barn was never used for hay again, though. In 1971, a family called the Brennons purchased the property and renovated the structure to include a four-bedroom living space. They raised their two girls there before eventually listing the property, in 2008. In 2009, I moved in, fulfilling my dream of living in something that used to be something else.

Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about Milliken’s legacy, as my home has continued to offer refuge to various people in transition: the friend who just ended a relationship, the University of New England student who lost her campus housing, the restaurant server who was living in his car at the park-and-ride for lack of an affordable rental. More recently, my husband and I adopted an aging castaway dog whose original owners had let her wander into the woods, hoping nature would take its course.

When people from away first think of our town, they likely think of the Bush family or our reputation as a summer getaway. The more informed might know about our working waterfront or remember our shipbuilding history. But when I think of Kennebunkport, I think of the 3,600 year-round residents whom I now feel lucky to call my neighbors: The town nurse who stopped by each week to weigh my COVID-era newborn. The librarians, letter carriers, and grocery-store clerks who know me by name and ask after my family. The women who shower my babies with hand-knit hats and homemade quilts and who drop by with flower bulbs and vegetable seedlings just because. The snowplow drivers who were my customers at Wink’s, who took turns clearing my driveway on their way to breakfast, frustrating my hired plow guy enough that he finally quit.

It’s a feeling of community that I like to think Freedom Farm’s refugees also experienced, if only for a short time.

These days, I pull shifts at Alisson’s, a restaurant downtown. My commute — down Arundel Road, then a left onto North Street and around the sharp curve into town — is the exact route the refugees took to Sunday services in Ethar Milliken’s station wagon. The rattling, wooden-slat bridge has been replaced with a paved-over culvert, and several acres of pasture have been subdivided for new homes, but the road still winds to accommodate old wells, and there are still no traffic lights. When leaving late-night restaurant shifts, I often loop through the driveway of the Village Baptist Church and its parsonage to point myself back towards home.

So much is unchanged. Recently, I talked with Zbig about the stories coming out of Ukraine, the plight of a new wave of refugees, forced by war to flee their homes. “The word appalling is not quite strong enough,” he told me. “My mother, had she been around now, would’ve been aghast with what the Russians are doing.” I’m reminded of a line from an article that Bonell wrote about Milliken’s gift and the plight of the Parnas, Freedom Farm’s first family. “Always, there should be a reminder about many more Parnas in Europe,” he wrote. “May there be many more Millikens in America to match them.”

Some nights, as I lie in bed, I imagine the voices of past residents seeping out of the barn boards around me, like linseed oil from an old harbor building. I fall asleep to their conversations, imagining the volumes of joy and pain to which the barn has borne witness, and I wonder about its stories to come.