By Ron Joseph

From our December 2014 issue

March 8, 1945, started as a routine day for Dean Yeaton. His father’s remote logging camp on the edge of western Maine’s Spencer Lake had no electricity and no running water. In the morning, the 16-year-old trudged out to the frozen lake, dipping two pails into a hole drilled through 2 feet of ice, filling them with drinking water for the camp’s 14 loggers. He had just turned to head back to the kitchen when he was startled by an explosion of sound and motion: a dozen semi-feral pigs stampeding past him on the frozen shore. The stunned Yeaton had no way of knowing it, but the frightened animals signaled the beginning of the largest manhunt in Maine’s history.

The pigs had been spooked by the dozens of law enforcement agents who were, at that moment, combing the woods with bloodhounds, searching for three German prisoners escaped from the Hobbstown prisoner of war camp on Spencer Lake’s north end, a mile from the Yeatons’ camp. The three Germans had snuck away from an ice-harvesting job the day before, and when their absence was noticed at the POW camp’s evening roll call, camp commander Major William Marshall immediately dispatched pleas for state and federal help. The next morning, some 30 officers from the Maine State Police, Somerset County Sheriff’s Office, Maine Warden Service, and FBI showed up at Hobbstown — and at the Yeatons’ logging camp. Newspaper headlines trumpeted the prisoners’ escape and publicized the armed search efforts getting under way.

For those who’d supported bringing German POWs to Maine in the first place, the escape was unwelcome news. In 1944, at the height of U.S. involvement in World War II, Maine Congresswoman Margaret Chase Smith and Senator Owen Brewster had lobbied the federal government to send captured Germans to Maine in order to help alleviate an acute labor shortage. Both the potato growers and the paper mills, Maine’s largest employers, had been hit hard by the exodus of young men either enlisting or leaving the state for more lucrative defense industry jobs in Massachusetts and Connecticut. At the time, Maine led the nation in the production of potatoes and paper, and both resources were in high demand for the war effort. In 1944, the War Production Board had challenged Maine to increase its lumber production by 45 percent — an impossible mandate without an adequate labor force. So Smith and Brewster pleaded with the War Department to send German POWs to Maine to cut pulpwood and pick potatoes, downplaying the potential dangers of establishing fortified camps for enemy combatants in the Maine North Woods. The government acquiesced, and in 1944, some 4,000 German soldiers arrived at four primary POW camps in northern Maine at Houlton, Princeton, Seboomook, and Spencer Lake.

And now three of them were on the run.

Every cord of pulpwood cut from this moment on will help ensure victory in 1944,” announced O.A. Sawyer, a manager of the Hollingsworth & Whitney paper company and a strong advocate of POW labor. “Every battle our boys win means they’re keeping faith with us. Every tree we cut means we’re keeping faith with them.”

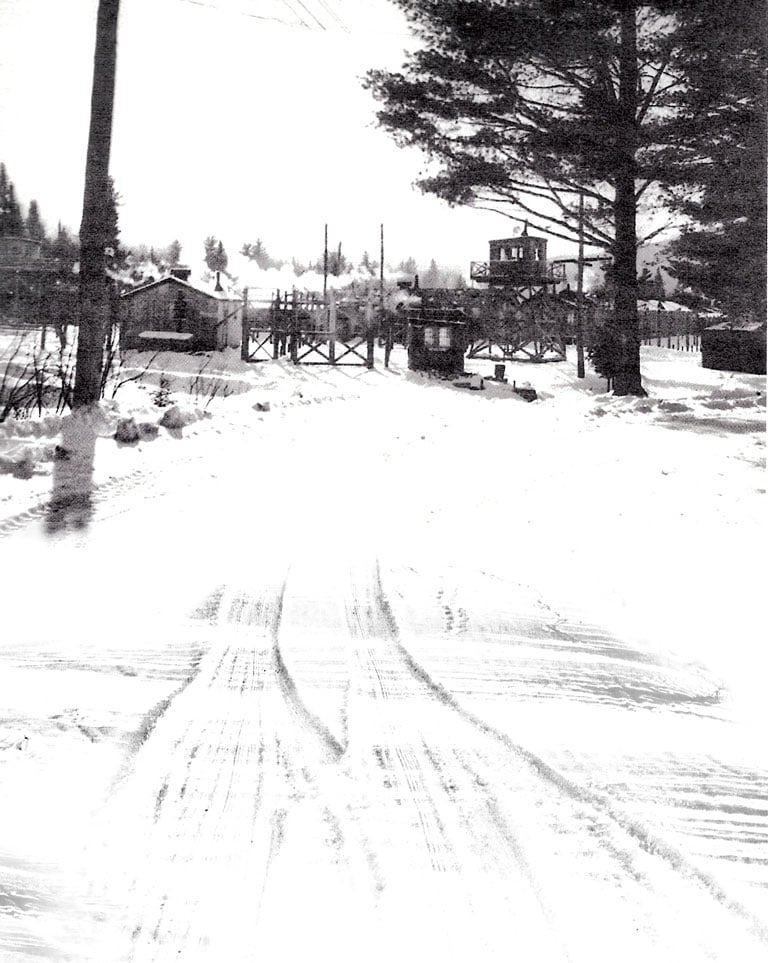

A beneficiary of conscript labor, Hollingsworth & Whitney constructed the 22-building POW facility at Spencer Lake. Surrounded by a barricade of barbed wire and guard towers, it was designed to accommodate 250 prisoners. At the peak of pulpwood production in March of 1945, the camp ballooned to 310 POWs, but the War Department turned a blind eye to the overcrowding, since Maine pulpwood was critical to production of artillery shell container paper, dynamite shell paper, map paper, card stocks, and dozens of other wartime paper products.

The Spencer Lake compound opened on a warm summer night in 1944 amid considerable public outcry. At 3 a.m. on July 10, a rowdy crowd in the town of Bingham met the passenger train carrying 250 POWs. The shades on the Pullman cars were drawn, so the prisoners couldn’t study the countryside, and armed guards stood at the end of each car. Roland Tozier was one of the locals watching as the prisoners filed out and boarded military trucks for the 50-mile ride to Spencer Lake.

“Seeing those frightened, young German boys headed to the Spencer POW camp softened me,” he said in an interview in the late 1960s. “I thought of my own two sons fighting in Europe and wondered if some German father was staring at my sons being carted off to a POW camp in Germany. I left the train station with a heavy heart.”

Many of the Spencer Lake POWs had served as members of General Rommel’s elite Afrika Korps. Captured in mid-May of 1943, when the Allies defeated the Germans in Tunisia and Morocco, they were among the thousands of POWs shipped to Boston, New York, and Norfolk. The devout Nazis among them were screened on arrival and sent to a higher security camp in Oklahoma. Most of the POWs shipped to Maine, meanwhile, had already worked as cotton pickers in Louisiana the year before.

There were no escape attempts at Spencer Lake during the camp’s first eight months. That changed when 18-year-old Franz Keller, 19-year-old Horst Schlueter, and 20-year-old Antone Geib woke up on March 7, 1945, hid some rations and sugar in pouches beneath their clothes, and then stole away into the snow-smothered Maine woods.

The trio fashioned crude snowshoes from rail ties and short boards, making harnesses out of discarded leather belts and stovepipe wire. They were armed with homemade knives. They absconded with axes from their work detail and stole a map from a French-Canadian woodcutter. They even rigged themselves an ingenious compass, made from a sewing needle, a magnetized electrical coil, and the tin top from a can of peaches (“The compass worked as well as any from L.L.Bean,” one game warden later remarked). The nearest public road was 12 miles away across a wintery wilderness. The Germans’ plan: to somehow make it 100 miles to the coast, where they hoped to hitch a ride on a freighter to German-friendly Argentina.

Shortly after the escape, officials interrogated the ice-cutting prisoner crew that the three fugitives had deserted. The guard assigned to them, the prisoners confessed, had fallen asleep on a horsehair blanket beneath a fir tree.

“The guards were very lax,” a Houlton POW named Hans Krueger later told a researcher. “You could watch them sleeping and dozing in the daytime. We would throw small pebbles or stones against the guard towers. Sometimes it would take 10 minutes to wake them up.”

For two days, three surveillance planes flew above Spencer Lake while law enforcement officers searched for clues on the ground, but no one found any signs of the escapees.

Prior to the escape, visiting military officers had voiced concerns about security at Spencer Lake’s wood harvesting sites. No need to worry, Major Marshall’s men had assured them: Maine’s forests were remote, and the freezing temperatures would dissuade any potential escapees. What’s more, very few prisoners spoke English, and many had seen enough Hollywood movies to believe that the woods were swarming with bears, wolves, and bizarrely, hostile Indians.

“We had been told the forest was populated by wild Indians who would not hesitate to kill escaping prisoners,” recalled a POW named Rudi Richter. “We had no reason not to believe these stories.”

But Keller, Schlueter, and Geib were unfazed by such tales. What’s more, the young soldiers were skilled at avoiding detection. They traveled at night and built shelters from snow and pine boughs to protect themselves from the bitter winds. For two days, three surveillance planes flew above Spencer Lake while law enforcement officers searched for clues on the ground, but no one found any signs of the escapees. Then, on the third day, help came from an unexpected source: an eccentric, cantankerous hermit named Bill Hall.

Motivated by a distaste for people and civilization, Hall had lived since 1932 in a squat, one-room trapper’s cabin halfway between the logging camp and the POW compound. Law enforcement officials were well aware of the hermit’s prickly nature, but Hall knew the woods better than anyone, and as the Germans’ trail grew colder, officers reluctantly deputized him. Dean Yeaton, who’d watched the frightened pigs trample through his father’s logging camp, befriended the reclusive woodsman over the years.

“Hall knew the woods like the back of his hand,” Yeaton later recalled. “His first contribution was unconventional but noteworthy. He killed a deer with a high-powered rifle, within earshot of the interned German prisoners. Hall placed the deer’s organs in a grain bag and carried the sack over his shoulder to the POW fence. There, as Germans gathered behind barbed wire, he dumped the bloody contents onto the snow and said through an interpreter, ‘This is all that remains of one escapee.’”

The dramatic gesture might not have had quite its intended effect, however. Hall tried to punctuate his point with a German phrase he had learned the previous day. “Binden sie ihre schuhe,” he growled through the fence. What Hall thought he had said was, “Let this be a lesson to you,” but his interpreter corrected him. The hermit instead had announced, “Tie your shoes.”

But Hall made no further mistakes. He advised game wardens to rush to the town of West Forks, some 12 miles east of the lake. The young Germans would head in that direction, the hermit assured them, after finding they couldn’t cross the open water of Spencer Stream or the wide and fast-moving Dead River to the south. Focus your search around West Forks, Hall advised, near where the Dead River meets the Kennebec — that’s where the icy rivers will funnel your Germans.

As Hall expected, two game wardens quickly picked up the Germans’ trail near West Forks. On March 12, 1945 — five days after their escape — the Germans were apprehended at gunpoint in a makeshift lean-to. The wardens relieved them of their axes and took them to a country store nearby, where the Army could retrieve them. According to Yeaton, “Hall never received the credit he deserved because he shunned publicity. He lived each day in blissful anonymity.”

Later, while being interrogated, one of the escapees told his captors that the overconfident camp overseer, Major Marshall, had actually challenged the prisoners to try and flee. “We wanted to show him,” said the soldier, “that it is possible to escape from the Spencer Lake POW camp.”

It wasn’t mistreatment that motivated the three young Germans’ flight from Spencer Lake. In fact, the impetus to escape was one many Mainers can relate to: “We did not want to endure another summer with biting mosquitos, blackflies, and no-see-ums,” one of the runaways later confessed.

On the whole, German POWs in Maine reported fair treatment. Major Marshall and the commanders of other camps abided by the Geneva Conventions in the expectation that American POWs would receive similarly humane treatment in Germany. After the escape, a Red Cross representative visited Spencer Lake to ensure that guards weren’t retaliating against the prisoners. As the Red Cross rep finished his inspection, a German soldier representing the POWs voiced a complaint: the prisoners were fed up with American white bread. The official relayed this grievance to Major Marshall, who responded by providing the Germans with what they most craved: a Dutch oven and ingredients for dark German breads.

Some German POWs actually had fond memories of their imprisonment. Later in life, many made emotional trips back to Maine to renew friendships forged between 1944 and 1946.

The Hobbstown POW camp operated at Spencer Lake until April 1946, 11 months after Germany’s surrender in World War II. With their homeland devastated by the war, not all German POWs were eager to return to the Fatherland. Even after having their rations reduced following the liberation of American POWs, many Germans volunteered to stay and dismantle Maine’s POW camps. With little food and no pay, they slept on mattresses on the barracks floor, determined to forestall their shipment to England or France, where other POWs worked as coal miners under deplorable conditions.

Some German POWs actually had fond memories of their imprisonment. Later in life, many made emotional trips back to Maine to renew friendships forged between 1944 and 1946. One of them was Franz Keller, the youngest of the Spencer Lake escapees.

Keller served a three-week solitary confinement sentence at Houlton’s POW camp after his capture in West Forks. As a POW in Houlton in 1945, he took full advantage of the educational opportunities afforded prisoners. He completed an astronomy correspondence course through the University of Maine and continued his studies after being returned to Germany and discharged from the military in 1946. In 1957, the young man who’d escaped Spencer Lake with the genius tin-can compass returned to the United States as an engineer. He worked for a company contracted by NASA to assist in the Apollo missions and later received a NASA commendation for developing space exploration technology. Keller became an American citizen in 1961. In 2000, he passed away in his adopted city of Boston, leaving a wife and two sons.

After the war, many former German POWs remembered their kind treatment in poignant letters to local families and the American men whom they worked alongside. Many letters share sentiments with this one from 1947, written by a released POW named Helmuth Claussen to a former paper company coworker:

I, Helmut, am sending you my heartfelt greetings from Germany. I am thanking you from the bottom of my heart for your dear letters. Healthwise I am doing very well, and I hope you are doing the same . . .

I often think of the beautiful times I enjoyed with you folks in Houlton. I hardly noticed that I was in captivity. I always had enough to eat; every day I could eat my fill and chocolate was plentiful, not to mention all the other plentiful things. All these are beautiful memories. The things I enjoyed while there I will, both now and in the future, have to deny myself. It will take a long time before we enjoy such things here again. Yes, my journey was very long. I had to spend four weeks in France. Many of my kameraden are still in France, working in the coal mines . . . It is a terrible shame that these young men have to experience this . . .

I would love to spend some time with all of you again, but, as my father is no longer alive I have to look after the family. I am so sorry, I have only one small photograph to send you.

Dean Yeaton was among those who appreciated the work ethic of the German pulpwood cutters.

“The Germans loved to sing ‘Don’t Fence Me In,’ the 1944 hit song by Bing Crosby and The Andrews Sisters,” Yeaton remembered. “It was the only English they knew, so they sang that song over and over. When I hear that song today, I think about those German boys who were only a few years older than me. They were teachers, musicians, and engineers. And like our soldiers, they were just doing what their country asked of them.”