By Francis W. Hatch

From our August 1972 issue

My introduction to Bucky Fuller (R. Buckminster Fuller, the architect-philosopher, that is) was purest slapstick with the zany touch of an old Laurel and Hardy movie. Time: a winter’s evening in 1916. Place: Harvard University. After a bout of study, I had slushed up to Harvard Square and the Waldorf Cafeteria around midnight for a snack. I had settled my plate of baked beans, roll, and coffee on an enamel tabletop and was applying the ketchup in liberal jets. Suddenly, through the revolving door there appeared a boulevardier-type built low to the ground: white tie under Arrow collar, white silk muffler, black coat with velvet collar, and patent-leather pumps. Obviously, a sophisticated Harvard pigeon homing from a debutante party at what was then the Copley Plaza.

Without warning, the modish young rake-hell broke into a dash and a swoop, hurled himself to the tile floor 10 feet from me, and hooked my table with his ankle as he slid by. Beans and ketchup spun off, smearing my midriff. For more than a half century, I have waited for an explanation of that unprovoked act. I received it last summer direct from Bucky himself on Bear Island, his summer retreat on Penobscot Bay. “I was just showing you my Rabbit Marranville slide,” was the way he dismissed the long-ago midnight mayhem. Come to think of it, Bucky is built like the Rabbit, the darling of Boston’s old Braves, whose vest-pocket catches and fall-away slides were big factors in lifting the team from last place in July to a pennant in September during the season of 1914.

The simile doesn’t end there. For years, in the early days of his career, Bucky was struggling in the minor leagues of science. No one took him seriously, not even Harvard, which he had left without a degree. Suddenly, from obscurity, Bucky went into orbit — geodesic orbit — wafted upward on the wings of his now famous dome.

Today, he continent hops as frenetically as presidential adviser Henry Kissinger. In recent years, he has logged over 200,000 miles for conferences with heads of state, architectural forums, lectures, tours and, above all, visits on campus with young people. You might believe that a man who machine-guns his words at a pace of 7,000 an hour would put youth to sleep. On the contrary, his college audiences will take two hours nonstop from the platform and clamor for more.

In the straightjacket of such a schedule, with its exhaustions, pressures, and frustrations, he has never lost his sense of humor — the Tom Jones stuff that spilled the beans in Harvard Square.

The excursion to the Olympus of Bear Island was Norman Cousins’s idea. Norman, the renowned editor, is an old friend of Bucky’s who once accompanied the inventor-poet-philosopher on tour in the Soviet Union. To visit Bucky, he had chartered a small schooner in Boothbay Harbor and sailed his family to Castine. There he planned to gather up friends and make a day’s picnic of it down the bay to Bucky’s island den. It didn’t work out that way.

A hard westerly had piled up rough going at the mouth of Castine Harbor. The Mary E, lightly powered, had struggled out under fores’l and jib. With the wind rising, the young skipper turned back. It looked like a picnic tied to the town wharf and a note of apology to Bucky. Not so in Cousins’s book. He dashed uptown to the local telephone booth. He couldn’t reach Bucky, of course, for Bear Island has no telephone, but it does maintain a G.H.Q. ashore, a farmhouse in the community called Sunset, on Deer Isle. There, a resident and very patient managing secretary gathers up and organizes mail, messages, and cablegrams for disposition when Bucky shows up. In three cars, we headed for the command post. By 2:30, we were waterborne again, this time on board a lobsterboat on the half-hour run to Bear. A cruise through the Greek Islands may well be Utopia, but to skim past clustered Maine islands that bear the Yankee names of Pickering, Bradbury, Eagle, and Butter on a blue day with the Camden Hills as a backdrop, is heady stuff in itself.

Great Spruce Head, which lies along the route, is now known to thousands through Eliot Porter’s magnificent picture book, Summer Island. Next door to it, and directly to the west of Bear, is Little Spruce Head, the scene of several of Bucky’s experiments with nature and the elements.

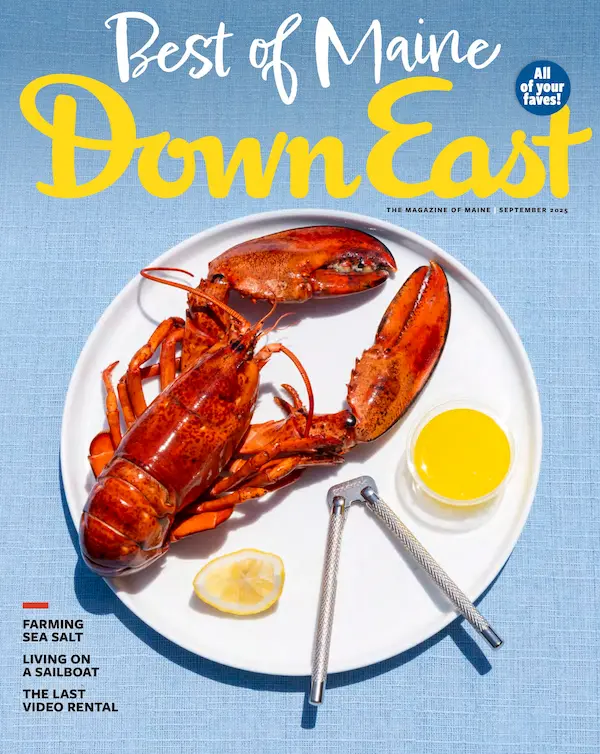

The snug little harbor at Bear Island is like the crook of a man’s arm. A great granite fist is cocked to deliver a knockout punch to a winter’s gale from north to east, making lobster fishing from the island a practicality in rough months. Lobster pots nest around weather-beaten buildings on the waterfront. The sheltered harbor could have been a haven for a privateer in the lusty days when the Yanks were playing cops and robbers with the irate British. A small vessel could be tucked away unseen in the inner reach.

At 2:45, we were tied up and walking along the wharf. Now long past the hour of the planned picnic with Bucky, it seemed wise to unlimber the baskets on the tidy little beach by the side of the road, while Norman took off for the house to see what was what. The chosen beach was a miniature set which the Garden Club ladies would adore to create at the annual flower show. There were driftwood logs for seats with streamers of purple vetch entwined. Bunches of purple asters stood in the grassy fringe, and tall beach dandelions growing in the shale were flaming torches of welcome.

While the ladies were readying the stuffed eggs, I strayed away to investigate a strange-looking contraption resting on the ground behind a boat shed. Two very thin, 20-foot, cigar-like pontoons were braced and strutted into a rakish catamaran. Rigged above was a rowing seat with slides and foot braces, outriggers, and swiveled oarlocks. I learned that this is one of Bucky’s creations, dubbed “Rowing Needles.” In his youth, he had been fascinated with the force of surface tension, which will hold a needle on the surface of a glass of water. Why not put the principle to work and rewrite the rowing record book? Aussitôt dit, aussitôt fait. Someday you may find the nautical daddy longlegs in the L.L. Bean catalog. It has great seaworthiness in choppy water that would sink a sculler in a single.

Bear Island has everything needed to provide rest, isolation, and inspiration for the man who returns to it every summer. For the naturalist, geologist, or zoologist, here is a living laboratory.

“Here,” as Bucky puts it, “I can think big.” Here, from the most reliable teacher of all, Nature herself, he probes for the discovery of secrets and dreams up ways to apply his findings for the benefit of the oncoming. Here, on the bluffy headland where his house stands, he can feel and be stimulated by the force of the wind. “Why not put it to work?” he said.

“Let’s set up a wind machine over on Little Spruce Head which will reverse the principle of the jet engine. We’ll take in wind force and harness it to a compressor. In time, we’ll find a way to make our own supply of liquid oxygen.”

All summer, a young scientist from Wisconsin was working at the wind machine, cutting, fitting, refining, and dreaming of the improvements that must be worked out before the machine finally becomes practical. Want to bet Bucky’s man won’t make it?

Bucky is fascinated by bird flight — the gulls that coast effortlessly overhead. He is intrigued by the fish hawk that will hover 150 feet above the cove with an eye like the Norden bombsight. Suddenly, the bird folds its wings and plummets down, splitting the water. Seconds later, it emerges with a sculpin in its talons, barely able to take the victim on its last airborne ride to the straggly nest and destruction in the spruce top. “It’s all part of the rhythm of nature,” Bucky will tell you. She’s the old girl who knows the answers to his questions.

There is but one large house on Bear Island — the gambrel-roofed, shingled summer house which Bucky’s parents built in 1908. Like a band of London adventurers setting out for the Virginia Capes, the senior Fullers, conservative Bostonians, had chartered a schooner, loaded aboard building materials, along with a carpenter and a stone mason, and headed up the coast. Annually, Bucky, in the short pants of Milton Academy, returned to the island, learning to sail, swimming in the chilly water, and hating to go home when Labor Day rolled around.

Tucked away in sheltered pockets around the island are smaller houses for the Fuller young fry, with an old farmhouse serving for a family rendezvous at mealtimes on summons of a bell. Around the tables after lunch, conversation can be disciplined or explosive, according to the Fullers’ visitors and guests at the moment. Despite the island’s isolation, there are always those who must make the trek to have a word.

It might be expected that the man who dreamed up the Dymaxion house, the Dymaxion car, which three-wheels along at 120 miles an hour and turns in less than its own length (I rode in it once at a Harvard reunion), and, of course, the triumphant geodesic dome, would make his habitat a mass of modern gadgetry. On the contrary, Bucky wants no part of it. The house is without telephone, running water, electricity, or any of the other so-called modern conveniences. Drinking water comes from a deep well in the meadow. Water for household use is trapped, Bermuda-style, in gutters along the edge of the roof and conveyed by gravity into a cistern in the yard.

After a walk along paths through the fields, we gathered in the living room of the main house. Cousins, with his instinct as an editor, saw to it that the moment did not drift away and evaporate in small talk. Pulling chairs together in a semicircle, he installed Bucky as Socrates in the center of his student group, ready to parry and thrust with all comers.

Cousins: “What would you say has been your greatest achievement during the past year?”

Fuller: (After a reflective pause.) “It might be the talks I have had with Indira Gandhi, or the fact that I am designing three major airports for her country. Or it could be the series of conferences I have had with Prime Minister Trudeau over the future development of Canada. We have discussed the possibility of a power grid across Canada to link up the waterpower resources of China. Or it could be the great honor which has come from Archbishop Makarios, who has delegated me to design the Peace Center on Cyprus. I shall build it on high ground as the Greeks used to do. And the vast sky above will remind man that he is after all a trivial creature in the scheme of things. But I suppose, most of all, I have felt satisfaction in the reaffirmation that youth trusts me and wants to hear what I have to say. Young people flock to my lectures and remain to fire questions at me long after a normal lecture would have terminated. This is a humbling experience and a compliment to me which I do not take lightly.”

Hatch: “I hear, Bucky, that you have invented a dance routine. Could you demonstrate it for us?”

Fuller: “Certainly.” (Rising.) “You see, one of my legs is a trifle shorter than the other. That’s what gives the thing an off-beat rhythm.” (With that, Fuller goes into a combination of clog, soft-shoe, tap, and country hoedown so infectious that Ellen Cousins, Norman, and Hatch join in a snake dance following the leader.)

Hatch: “How about a musical comedy based on your life? We could call it Bucky and take you from Milton to Bear Island, Harvard to Expo, Houston and the United Nations, closing with:

Bucky, in the shelter of your dome

You gave the Houston Astros

An astro-turfish home.

You turned to Mother Nature

For fundamental truth.

Bucky, you’re a beacon,

A catalyst for youth.

Fuller: “As a matter of fact, one of my verses has been incorporated into the lyrics of a Broadway show.”

The session ended with Bucky calling for cardboard and scissors. Deftly cutting and fitting, he fashioned a miniature model of his world trademark, the geodesic dome, which shuns the 90-degree angle and incorporates what he has discovered to be Nature’s basic angle of 60 degrees.

“Take this back to Mary McCarthy at Castine and thank her for the piece of cake you left me. (Mary, the writer, had baked him a “dome cake.”) And you might give her this poem I wrote in the garden of the Shah of Iran.”

With Bucky’s permission, here are a couple of stanzas showing how the poet-engineer fits love into the 60-degree angle.

Love

Is omni-inclusive

Progressively exquisite

Understanding and tender

And compassionately attuned

To other than self.

Microcosmically speaking

Experience teaches

Both the fading away

Of remote yesterdays

And the unseeability

Of far forward events.

As we walked downhill to the wharf, a silvery shape caught the rays of the setting sun. It seemed to be a plastic dome, about eight feet tall, covered with a translucent skin. It stood on the remains of an old cement tennis court and had been in place throughout the winter, proof of its sturdiness. The outer skin was quilted with diamond-shaped panels. Through its translucence, two cots and chairs were outlined. Bucky calls this his “Pillow House,” for each skin blister is filled with an inert gas, which provides protection from cold or heat. It is the answer to dome living on a small scale — the perfect portable guesthouse or one-room living for the young in heart.

New Jersey may have the memory of Thomas A. Edison and the shrine of his laboratory. But Maine has Bear Island and Bucky Fuller going strong — the audacious dreamer and doer with a phenomenal hold on the hearts and minds of youth.