Turning the corner at Crow Point and making a right into the mouth of Brookings Bay, I’m aware of a sudden quiet. I’m paddling a kayak deep inside the furrowed pleats of the midcoast, alongside my 16-year-old son, Vaughn, and our guide, Oliver Dominick. All morning, our banter has been light and the wind has nuzzled our backs as we’ve skimmed past a raggedly beautiful, brooding landscape. Into the gentle swells of the Back River, countless stony fingers of land and delicate, pine-draped nubbins poke out at random — a topography like splattered Bisquick batter. We’re only 3 crow-flying miles east of Bath Iron Works, but the river feels far more remote. Despite immaculate early-summer weather, we’ve seen no one else since we pushed off.

One of Maine’s countless Ram Islands hulks to our left. Dominick declares, “Well, here we are.” He had described the bay as one of the most beautiful in the area, a favorite place to go duck hunting. Vaughn and I murmur in acknowledgment, and then the only sound is the soft sploosh of paddles cutting water. A cormorant flaps off silently, not bothering with its bronchitic lament.

I’ve been imagining this moment for at least two decades, ever since I began to comprehend the depth of my ancestry on this bay. My forebears in the Brookings clan lived on and farmed the land atop this tidal basin in Woolwich for nearly 200 years, beginning in 1738, and the family’s history here actually reaches back to the 1600s. For years, I’ve visualized my triumphant pilgrimage “back,” to walk the land and find the private family burial ground where Brookings gravesites date back more than two centuries. But I’d always been too far away and too preoccupied to pull off a trip. Even since moving to Portland from Pennsylvania two years ago, I’ve been too busy with work and family matters to find the time.

Now, I’m within a few hundred yards of making landfall at my ancestral home — and the clock is ticking.

Finding details about the family’s plot had been a challenge. I pinpointed the location on a 1740 map of Woolwich, then also known as Nequasset Plantation, and reached out to Debbie Locke, board president of the Woolwich Historical Society. She’d been hoping to visit the old cemetery but wasn’t sure who owned the land — anyway, she said, she thought the path that once led to it was overgrown. I called Dominick, who runs Abkenoc Guiding from his home in Phippsburg, and he proposed a paddling route. Locke and Dominick put out feelers around Woolwich, and a couple of weeks later, a neighbor reached out on behalf of the landowner, giving us a green light to visit. The cemetery, he said, had grown over with bittersweet. Locke warned it might be hard to find on what had been a 100-acre farm.

“Please don’t set your hopes too high,” she told me.

I glance at my watch — it’s almost noon. Tides on the Back River are tricky, Dominick had warned, meaning we had a short window to arrive, roam around a bit, and then take off again before the patch of bay we’re paddling on turns into a mudflat. Dominick points out our destination: a slender patch of open green carved into an expanse of wooded shoreline. There’s still no one in sight, but off to the left, Vaughn spots a deer browsing on a far-off shore. We paddle towards the break in the trees.

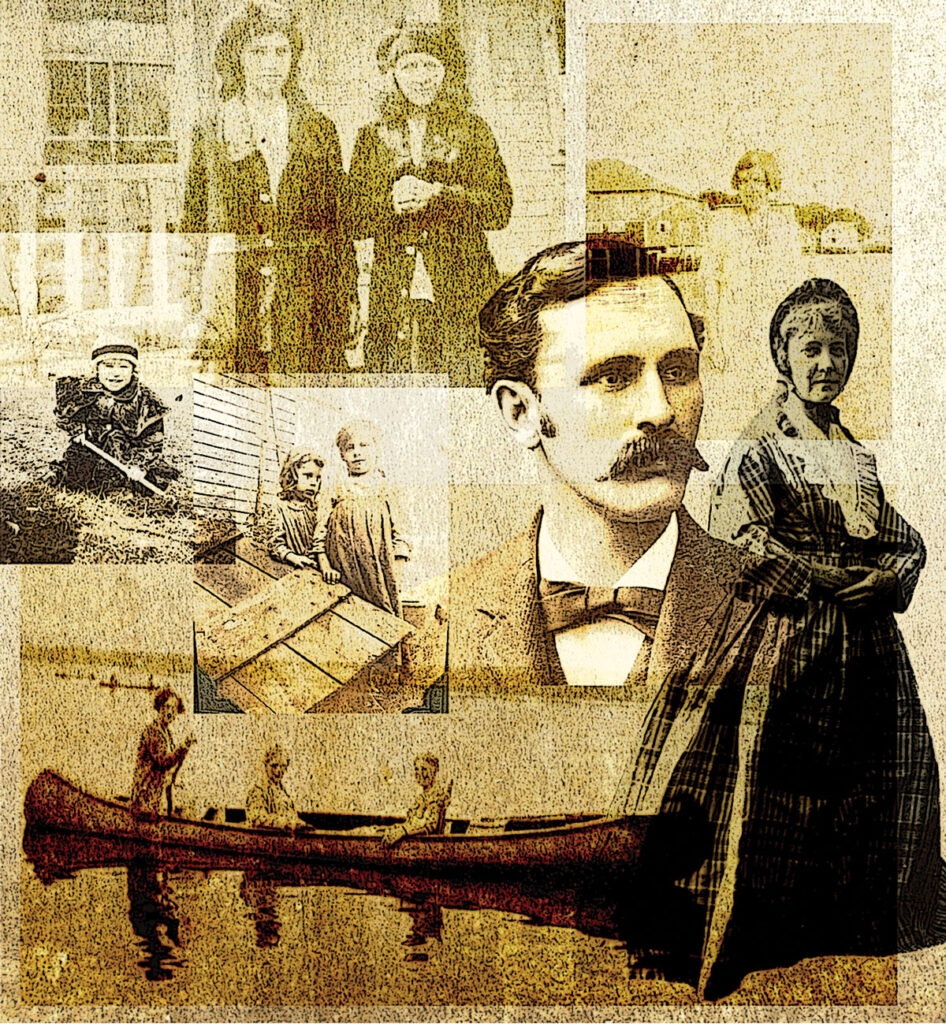

Of course, any uncertainties I face on this casual expedition are laughable compared to what my ancestors contended with. The land on what became Brookings Bay was first claimed in the mid-1600s by the Wadleigh family, who came from Wales to claw a life out of the hardpan and the marsh grass. The Wadleighs are otherwise little mentioned in our collected family history, an assemblage of photo albums, news clippings, genealogical charts, diaries, and more, collected in several boxes by my great-aunt Mimi. It’s a collection I became fascinated with a few years back, after my uncle described to me the out-of-the-way setting of the old Brookings farm, which was, to hear him tell it, most easily accessible by water. That started me daydreaming about a visit, and it prompted the realization that, as a journalist, I had dug deeply into other people’s lives and backgrounds but never subjected my own history to the same scrutiny. So about three years ago, my older brother and I excavated Mimi’s boxes from his basement, and when we flipped the lids open, several centuries of stories came to sepia-toned life.

Combing through these materials, I learned the reason for the Wadleigh clan’s quick disappearance from our family history. The area’s original inhabitants, likely a band of the Wawenock tribe, overran the Wadleigh farm in the 1670s, burning it down and presumably killing everyone they encountered. But a child, Sarah Wadleigh, escaped and was later found wandering the marshes. She was shipped to Newburyport, Massachusetts, where, years later, she married Henry Brookings, of the Isles of Shoals. They had a son, also named Henry, who emerges as a key figure in family lore.

Even as he raised a family in York, this Henry was a restive, adventurous soul. As Aunt Mimi’s sweeping, typewritten history explains, “Henry, interested and attracted, doubtless, by his mother’s stories of her childhood home, determined when the Indians were no longer on the warpath, to seek possession of his grandfather Wadleigh’s land which had remained desolate for 60 years.”

In August 1737, the state of Massachusetts, noting that his grandfather “was an ancient settler upon some part of these lands,” deeded him 100 waterfront acres in Woolwich. The following year, Henry Brookings loaded his family and their possessions in a boat and floated on the tides past Crow Point and Ram Island. The story goes that his elderly mother, who had fled the burning property as a child, piloted the craft.

The family reestablished a farm but was still, it seemed, less than welcome. According to Mimi, Henry was looking for stray cows one June morning in 1748 when he was attacked by a Native band.

“Henry fell,” my aunt wrote, “never to rise again.”

This time, though, the Brookings clan wouldn’t be chased off. Instead, the family dug in deeply enough that the name of the tidal basin bordering the farm was changed from Wadley’s Bay (an old variation of the spelling) to Brookings Bay. Generations unspooled: there were Brookings shipbuilders and Baptist ministers and soldiers. Jude, who captained a boat, was lost at sea with his wife and child in 1859. Wilmot attended Bowdoin, then headed west, becoming governor of the Dakota Territory. Despite having both feet amputated after surviving a blizzard in 1858, he became a towering figure of the pioneer era, the namesake of two different towns and a county in South Dakota. Then there was his brother Rastus, tersely memorialized in family lore as a “criminal, freed by brother Wilmot on condition he disappear.”

But the person I most identified with was Henry, the man who set all this history in motion by deciding, at almost 50, to revisit the charred and blood-soaked ruins in this wild place. Like him, I was restless, prone to pulling up stakes and moving just because it’s possible to do so. Like him, I wanted to return to a place I had never been.

We hover at the edge of the land, peering at the property through an irregular row of oaks near the shore. Much of what’s visible from the bow of a kayak seems impenetrable, but here, a meadow rises up and away, with a lane the width of a school bus mowed through it. In the far distance, I see the white dot of a house. I half expect to run into a curmudgeonly figure waving an old Remington, but no one is around.

The skeletal remains of a duck blind sit on partially exposed flats, and a few feet beyond, above the water line, is a picnic table and fire pit. There’s no obvious place to land the kayaks, so we paddle downshore until we find a grassy incline, low enough to clamber out. Dominick’s gregarious black Lab, Winnie, who rides on the back of his kayak, hustles off to explore as we get our bearings.

A few days earlier, I’d described my planned trip to my Uncle Don, who lives in Massachusetts. His mother — my grandmother — was born on the farm in 1904. I’d expected him to be excited about my visit, but instead he asked, “What is it that you think you’re doing there?”

The question caught me off guard. I’d become so preoccupied with the logistics of getting to the site that I hadn’t spent much time interrogating my motives. I stammered something to Uncle Don about being interested in my roots, but in truth, what I’m interested in is belonging. When I was 17, I left the small Connecticut town I grew up in, and in the 35 years since, I’ve lived in more than half a dozen places, ranging in population from fewer than 2,000 to more than 8 million. I know where I grew up, but I’m no longer sure where I’m from.

Throughout my life, Maine has loomed as a mythic, beloved place. During my childhood, we spent a week every summer at a friend’s cottage in Port Clyde, skittering across rocky beaches, splashing in the frigid Atlantic. I returned often in my 20s with family and friends to raft the Kennebec and Penobscot. When I took a DNA test from an ancestry website, the site spit back a map with a bright-orange circle over the state’s central and southern coast: “Maine Settlers” read the designation.

Still, even now that my family and I have moved to Portland, I’ve hesitated to call myself a Mainer — it feels presumptuous just to show up and invite myself in like that. So in a sense, that’s what the expedition was about. Maybe, I thought, a visit to this property, and to the burial ground, might ripen into tangible proof that I was actually from this place — that I belonged. Reading about Henry Brookings, I was intrigued to realize I was only slightly older than he was when he’d returned to claim this land. I wondered if some sort of midlife homing instinct was kicking in.

Later, I asked Dominick whether he thought it would ever make sense for me to think of myself as a Mainer. A transplant who moved to the midcoast some 20 years ago, Dominick is an outdoors polymath: a duck hunter, angler, FAA-certified flight instructor, and mountaineer, among other things, plus he holds a PhD in neurobiology and has conducted research on infectious diseases. Seemingly overqualified for a kayaking guide, he brings an erudition to his work that emerges in his stories and observations about the landscape and local culture. On the subject of what it takes to be a Mainer, though, Dominick shrugged and fell back on aphorism. “Just because a cat has kittens in the oven,” he said, “don’t make ’em biscuits.”

It’s a joke as old as Maine humor: a person isn’t really from Maine unless their familial line extends so far backwards it recedes into the mists of time. Of course, mine actually does. Almost 100 years ago, though, that line was broken.

Between 1902 and 1906, Winfield and Rossa Brookings had three girls, including Ethel, my grandmother. In 1910, they had their first boy — but Chester, who presumably would have grown up to assume the bulk of the physical farm labor, died before turning 3. The family scraped by for another decade, although they were uncertain how long they could manage the place. Then, in December 1923, 61-year-old Winfield was chopping wood when his axe slipped. It’s a remote area. He bled to death before anyone could get help.

Shattered by these tragedies, the four Brookings women sold the family farm, packed up, and moved to eastern Connecticut the following summer. There, Ethel Brookings eventually met my grandfather. In all, 96 years passed between their departure from the edge of Brookings Bay and my arrival in search of evidence that it had all really happened.

As Vaughn, Dominick, and I start off in search of the burial ground, I’m doing as Locke, from the historical society, had suggested — not getting my hopes too high. All we really have to go on is a line written by Aunt Mimi, who grew up on the farm in the early 20th century. The cemetery, she wrote, was “in a field . . . sadly neglected. . . . The neat stone wall that once enclosed it has become a shapeless mass of rocks, and bushes nearly hide it from view.” That was several decades ago.

I start walking up the mowed lane, and I’m only a few dozen steps from the water, scanning the property, when I see, maybe 150 yards upslope, what looks like a shambling stone enclosure. I turn to Vaughn and Dominick and ask, “You guys don’t think there’s any chance that could be it, do you?”

As we hustle forward, some weeds poke into view, followed by the first of the headstones. The old marker is tilted 30 degrees towards the bay, and I stoop to get a look. It reads: “Mr. Abner Brookings, died May 17, 1850.”

I’m astonished: Here the cemetery sits, as conspicuous as can be. I couldn’t have missed it if I were as nearsighted as a mole.

The old enclosure is indeed overgrown with bittersweet, which makes it hard to navigate — not that there’s much to see. There are only a few other stones, the most distinct being a twin grave marker for Josiah, who died in 1823, and his wife, Annah, who passed a year later. That one is lying angled on a bed of vines. Vaughn reads one faded stone Braille-style, feeling the letters with his fingertips. There is no marker for Henry Brookings, but my great-aunt believed he was buried there, probably the first one laid in the ground as the family resolved to stay.

We circle the rectangular plot for a half hour, picking over it where the bittersweet is thickest, studying it from different angles. It isn’t much, but it’s everything.

When the other two start to wander back, I linger a few more minutes, standing at the top of the plot, looking over it, down towards the water. It occurs to me that what I wanted was simply for this place still to exist, for this history to become something more than just a projected image flickering in the motes and light of my imagination. The fact that it overlooks this gorgeous hidden bay only adds to its incandescence. Finding it doesn’t make me from this place — I’ll never be that. But I am of this place.

As we climb back into the kayaks and push off, I think about the muscular tides, the way they carry almost everything away with such force, only to sweep it back in again. Maybe they’ll eventually carry in someone else — maybe Vaughn’s great-granddaughter, curious about her story, her place on the planet. Maybe she’ll find this humble little burial ground and take in the view and know the truth, that we no longer own any of this part of Maine, but it will always be ours.