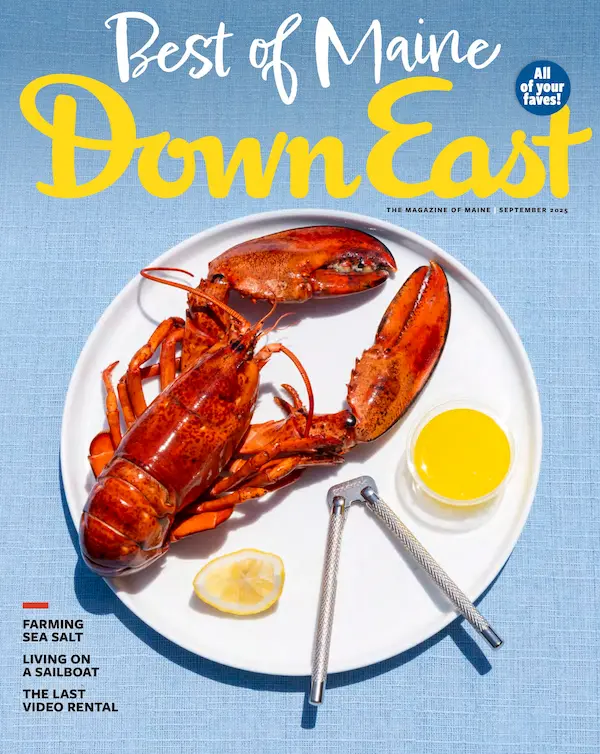

By Charlie Pike

Photos by Nicole Wolf

Styled by Catrine Kelty

From our June 2025 issue

I. A Recipe for Success

At Labadie’s Bakery, the 100-year-old shop in downtown Lewiston, cakes for the whoopie pies start going in the oven around midnight. At 3 in the morning, the person known as the filler arrives, presumably bleary-eyed. It’s her job to lather on the frosting. Two hours later, the capper comes in, tasked with applying the top piece of cake, putting the finishing touch on sugar-saturated sandwiches. By seven, the wrappers have showed up. They package the whoopie pies in little plastic pouches. Clicking at max capacity, the team at Labadie’s can make about 3,600 whoopie pies in a day. Customers, then, can buy them fresh from the bakery or have them shipped anywhere in the country.

Labadie’s sold its first whoopie pie in 1925, the same year the shop opened. That represents, by all accounts, the first recorded instance of a whoopie pie in Maine (although the actual records — part of a trove of old receipts and other paperwork the Labadie family kept — were destroyed in a fire in the ’60s). At the time of that inaugural whoopie pie, Odilon Labadie was running the bakery, having set up shop in the “Little Canada” neighborhood of Lewiston, where many French Canadians who found work in shoe factories and textile mills had settled. The story goes that the place was a hit from the get-go. “There were lines out the door,” says manager Dawn Emond, who’s been part of making whoopie pies and other pastries for 27 of Labadie’s 100 years. Old-timers around town will reminisce about how they’d run over after school to satisfy a sweet tooth or how they’d come in to sweep the floor in exchange for a treat. “Anybody who ever grew up down here,” Emond says, “they’ll tell a story.”

Nowadays, Fabian Labadie is the third-generation owner, overseeing a business that still occupies the same little storefront it always has. True to its history, it’s a no-frills operation for traditional bakery treats, especially doughnuts, cream horns, and whoopies. On Whoopie Pie Wednesday, a weekly occurrence, customers can buy half a dozen whoopie pies and get half a dozen for free. “People mark their calendars to come and get their week’s fill,” Emond says.

The classic formulation is, of course, vanilla filling smooshed between two rounds of chocolate cake. All around Maine, new flavor profiles have proliferated — mocha, lime, mint chocolate, lemon poppyseed — but the bakers at Labadie’s could be described as cautiously creative: vanilla frosting between vanilla cake or peanut-butter frosting between chocolate cake. Vanilla-on-vanilla that’s topped with a schmear of raspberry jam and a sprinkling of coconut might be the wildest they get. Emond’s personal favorite is a fall special — vanilla frosting between pumpkin cakes studded with chocolate chips.

The classic, though, is still Labadie’s gold standard, and Emond is emphatic about the vanilla filling being made with sweet cream. “No Fluff,” she insists, referring to the jarred marshmallow crème that has become a common ingredient in many whoopies over the years. It might be a controversial opinion, but she says, “That’s not a Maine whoopie pie.”

II. A Great American Bake-Off

Culinary history tends to be just as foggy, maybe even foggier, than the rest of history. Where and how exactly any one dish originated is, more often than not, nearly impossible to say with certainty. And while Maine can certainly make a case for being the original home of whoopie pies, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts have staked claims to whoopie-pie history too.

In Pennsylvania, the Amish get credit for coming up with whoopie pies sometime in the early 20th century. Supposedly, when Amish children and farmers would discover the sweet treats packed in their lunch pails, they’d exclaim, “Whoopee!” (although, in western Pennsylvania, whoopie pies are generally called “gobs” instead). That’s one version of the legend, at least.

Massachusetts has a story not about inventing whoopie pies but about naming them. In 1928, the musical comedy Whoopee! was staged in Boston. The play follows a woman who leaves her husband-to-be at the altar in pursuit of her one true love, snagging a ride from hypochondriac Henry Williams, whose character was played by multihyphenate entertainer Eddie Cantor. One of Cantor’s big numbers was “Makin’ Whoopee,” a song that charts the pitfalls of romance, marriage, and, well, the activity to which its title alludes.

At the time, in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury, the owners of the Berwick Cake Company were struggling to get people to buy the cake-and-frosting sandwich they had recently started making, but they evidently had a nose for publicity. They wrapped up those novel baked goods and sent them to the cast of Whoopee! One tale has it that the treats were tossed into the audience while Cantor sang “Makin’ Whoopee,” while another has it that they were dished out at curtain call. In either case, the little pastries found a name in the process.

It’s not so implausible, is it? After all, “whoopee” sells.

III. Politics Is No Cakewalk

On the list of bills on the docket for Maine’s 125th Legislature, sandwiched between “An Act Designating March 29th Vietnam Veterans Day” and “An Act to Require State Agencies to Give Priority to State Armories When Renting Space for Meetings,” like the creamy frosting between two chocolate cakes, was L.D. 71: “An Act to Designate the Whoopie Pie as the State Dessert.”

The bill, presented by Representative Paul Davis, from Dexter, could be read as an escalation in tensions with Pennsylvania over whoopie-pie provenance. The push started after Amos Orcutt, president of a trade organization of Maine whoopie-pie makers, read a 2009 New York Times story that contained, in his opinion, a heretical assertion: “Food historians believe whoopie pies originated in Pennsylvania.”

Orcutt, who told the Portland Press Herald he was “appalled and aghast,” responded by lobbying Davis to make Mainers’ affinity for whoopie pies statutory. “Let’s claim our rightful heritage before another state makes the whoopie pie their state sweet,” he later wrote in a letter to the editor. Davis attended the fledgling Maine Whoopie Pie Festival, in Dover-Foxcroft, one of the towns he represented, and felt inspired to act.

Pennsylvania whoopie-pie aficionados were none too pleased. In Lancaster County, where Pennsylvanians hold that whoopie pies got their start, a protest was staged, charges of “confectionary larceny” were leveled, and a petition circulated “objecting to any other state, county or town claiming the whoopie pie as its own.”

Davis was undeterred. At a committee hearing, he took a rather philosophical tack, touting whoopies as a symbol of unity. “We have two sides here in Augusta,” he posited, “and we have to find a way to have the filling between the sides hold them together. I would suggest a filling that has a tiny dash of tolerance, a bit of compromise, a lot of patience, and a realization that we all love Maine and want the best for her people.”

Not everyone was on board, and the hearing produced voluminous pages of testimony both for and against the bill. One constituent wrote to the committee that it seemed irresponsible to officially sanction something that doesn’t exactly qualify as a superfood: “We have a wonderful product in Maine. It is called the wild blueberry. I suppose the strong antioxidant effects and sheer healthiness of this fruit precludes it from any serious consideration by waist-expanding, high-cholesterol-promoting lawmakers.”

Another concerned citizen thought the whole thing seemed like a farce, writing, “I think there are a lot more important issues that our legislatures [sic] should be dealing with instead of wasting taxpayer dollars on such a frivolous issue as sponsoring a bill to find a state dessert. Why would we even need a State Dessert?!”

Fourth graders from Williams Elementary, in Oakland, held a class vote: 16 to 3 against whoopie pies as the official state dessert, although some of their reasoning seemed less than ironclad: “Whoopie pies are not really dessert; they are snacks”; “I would say no to L.D. 71 because the prices may go up and stores might not be able to sell as much”; “We live in Maine, so we’re maniacs. We need more sugar than a whoopie pie. We should have the most sugariest dessert in the USA!”

Among the supporters of whoopie pies as the state dessert, some had skin in the game, like Rollin Thurlow, then-treasurer of the Center Theatre, in Dover-Foxcroft, who wrote to the legislature that the measure would be good publicity for the whoopie-pie festival, which would in turn be good for the local economy. Others were inspired by more personal considerations: “I moved here several years ago and had never heard of them,” a recent transplant to Thomaston wrote, “but one taste was enough to convince me that this was a reason to put down roots.”

A great deal of wrangling — and considering the low-stakes subject matter — a surprising amount of strife ensued, but the bill finally passed, albeit with a key change: in a concession to blueberry diehards, wild-blueberry pie would become the state dessert (even though wild blueberries were already also the official state berry). The whoopie pie would instead become the official state treat. And so it has been ever since.

IV. Corporate Takeover

The Oreo Cakester is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a cake-ified Oreo, with a creamy filling between a pair of soft chocolate cakes, fresh off Nabisco’s assembly lines. And if that sounds an awful lot like a whoopie, well, it probably should. The Cakester has invited plenty of comparisons to its apparent inspiration since debuting in 2007, but it’s hardly a dead ringer. One food blogger deemed Nabisco’s interpretation “a disaster” that “tried to be a creamy, moist whoopie pie, but it felt as though it was put into the fridge where its moisture was drained.” Another wrote that Cakesters “taste just like an Oreo” and are “not nearly as tender” as whoopie pies.

Nabisco discontinued the line in 2012, then released it again in 2022. Bringing it back turned out to be a clever marketing move, as it triggered waves of sentimental hype among social-media influencers who remembered Cakesters from their (relatively recent) youths. The internet was suddenly chock-full of TikTokers and YouTubers chomping down on the treat. “This right here is my childhood,” one influencer declared, holding a Cakester up to the camera, emotional piano music setting the mood as he took a bite. “If you get an opportunity to be blessed with these, just cherish it.” Another sniffed the plastic packaging, kissed it tenderly, and, after finally unwrapping it and taking a taste of the Cakester, affected to sob with joy. Not everyone was so ecstatic. One reviewer, whose video has more than two million views, rated the product a respectable but not incredible 6.8 on a scale of 10, noting, among other deficiencies, that the Cakester could use more filling. “I think this was hyped up just a bit too much,” he said.

But even if the Oreo Cakester isn’t anywhere near as good as a proper whoopie pie, it does now seem to share at least one core characteristic with the superior treat: baked-in nostalgia.

V. Whooping for Whoopies

Next year, the 17th annual Maine Whoopie Pie Festival takes place June 20, 2026, at the Piscataquis Valley Fairgrounds, in Dover-Foxcroft. The celebratory affair will be packed with whoopie-pie bakers, other food vendors, crafts sellers, magic and wrestling shows, a whoopie-pie eating contest, and a whoopie-pie baking competition. New England food historian and Bangor-based writer Jim Bailey has helped judge whoopie pies since the very first festival, in 2009. So has Joy Hollowell, co-anchor of the morning news at Bangor’s WABI TV5, the local CBS affiliate. Together, they’ve tasted thousands of whoopie pies.

Bailey has strong feelings about process and aesthetics. He hates seeing whoopie pies made with cake molds. “I want to know that you actually know how to make a whoopie pie,” he says, “and the only way to do that is to use an ice-cream scoop, put [the batter] on the sheet pan, and bake it.” The result, he adds, should have a specific look: “If it’s not rounded, if it’s not slightly cracked on top, and just a little sticky, then it’s not a perfect whoopie pie.” Also, if he tastes granular sugar in the frosting, or if grease coats his mouth, he’ll be disappointed. Perfection, he says, is rare even in a humble whoopie pie, but “I always give points for trying.”

Still, he is hardly a purest. Although it flies in the face of the definition of a whoopie pie laid out in the legislation that designated the state treat — “a baked good made of two cakes with a creamy frosting between them” — Bailey has fond memories of a “whoopie pie” formed from cornbread cakes and filled with stuffing, turkey, mashed potatoes, and gravy. As far as whoopie pies that have adhered to the legislature’s definition, his other favorite was blueberry-pancake flavored.

Hollowell remembers at least one other savory cornbread “whoopie pie,” with a filling of macaroni and cheese and pulled pork. She’s also encountered Moxie-infused flavors, plenty of fruity flavors, and a riff on piña colada. “We’ve had alcohol in whoopie pies,” she says. “There was one year when someone entered a whoopie pie for dogs. We’ve had waffle whoopie pies. Cookie whoopie pies. We’ve had chocolate-covered whoopie pies, whoopie pies with Nerds candy in them, whoopie pies with Hot Tamales in them.” She once tasted a whoopie pie inspired by Elvis Presley’s favorite sandwich, with peanut butter, banana, and bacon. “It was fantastic,” she recalls.

At the end of the day, though, what Hollowell is really looking for, in her capacity as a judge, are whoopie pies that aren’t dry or crumbly and have an ideal ratio of filling to cake.

You know, the basics.