By Will Grunewald

From our May 2017 issue

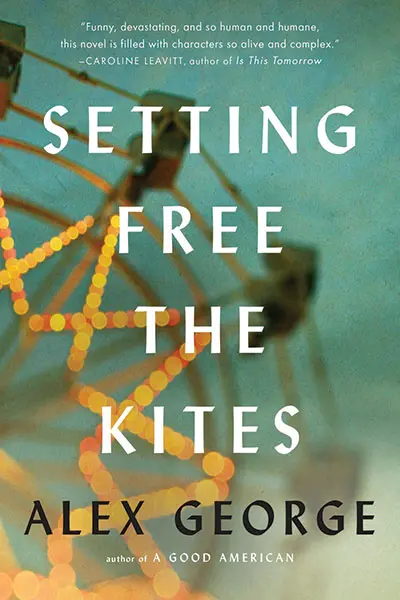

Haverford, Maine, the fictional locale of Alex George’s sophomore novel, Setting Free the Kites, got hit hard when its paper mill closed. Even as other communities enjoyed post-industrial comebacks — their old factories “reborn as art galleries . . . and organic delicatessens selling squid-ink pasta from Umbria” — Haverford got caught in a tchotchke-hawking, taffy-slinging, postcard-peddling rut. As George succinctly puts it, the whole town “stuck out a leg and pulled up its skirt.”

George’s vision of Haverford is both funny and familiar — maybe familiar to a fault, as if the British-born, Missouri-based author took a drive from Kittery to Bar Harbor and noted a handful of recurring features: abandoned mills, cutesy Main Streets, and ice cream stands. But if the lack of depth to Haverford is frustrating, it’s because it’s at odds with the author’s rich and original writing about the book’s other people and places, like Fun-A-Lot, a medieval-themed amusement park that becomes a hub of the action.

Fun-A-Lot (which sounds, in name, a lot like the real Funtown in Saco) is the one big attraction that draws tourists off I-95 and into Haverford. Tired of swimming, hiking, and boating, exhausted parents try to entertain their children, who invariably behave like “tyrannical cyclones of self-entitlement.” A mascot dragon gallivants about the park trying out cheer-inducing antics; teenage employees dressed as peasants and knights try to affect Old English accents; and a dour mechanic plays jazz songs in his head to block out visitor complaints. The place is a charming mess.

Robert Carter, the protagonist, is the son of the park’s owner, “a serious man who had the misfortune . . . to be involved in an unserious business.” Robert, a middle schooler, is surprisingly serious himself — the kind of kid who remembers Maine summers not as blueberries and ocean breezes but as bug bites and the “sour chemical whiff of antiseptic cream.” The deeper root of his unhappiness is his brother, whom he admires and loves and who’s slowly dying of muscular dystrophy. While his parents exhaust every bit of their emotional reserve tending to his brother, the only person who pays Robert much attention is Hollis Calhoun, the thuggish older boy who enjoys beating him up.

Then, one day, a new student named Nathan Tilly finds Robert and Hollis in a school bathroom and intercedes mid-swirly. Things start looking up for Robert, and soon, he and Nathan are fast friends.

Fast also describes the pace of the story from that point on. Shortly after our heroes meet, a tragedy befalls Nathan’s family. Already the dreaming, impetuous type, Nathan adopts an exhilarating but perilous passion for heights, climbing rollercoaster tracks, sleeping in Ferris wheel cars, and clambering high about Haverford’s old mill. And as will happen in coming-of-age stories, the presence of a pretty girl working at Fun-A-Lot tests the boys’ relationship. While Nathan hopelessly tries to win her attention, Robert, having just read The Great Gatsby, worries over his friend’s inevitable disillusionment, recognizing a parallel to Jay Gatsby’s misguided, ruinous pursuit of Daisy Buchanan. Nathan, meanwhile, prefers the love-at-all-costs moral he finds in a cheap romance novel by a fictional author named V. V. St. Cloud.

One suspects lovelorn Nathan is setting himself up for some calamity, although the exact shape of it remains unclear until the closing pages.

Playing around with the dueling influences of F. Scott Fitzgerald and V. V. St. Cloud, George may be winking at the in-betweenness of his own novel. If so, it’s a clever stroke, acknowledging that his book is neither highbrow literary fiction nor drugstore-paperback material. Rather, Setting Free the Kites is a serious but breezy work, a sad but delightful story, and just right for thumbing through at the beach this summer — maybe on some stretch of sand not too far from Haverford.