By Jaed Coffin

From our January 2020 issue

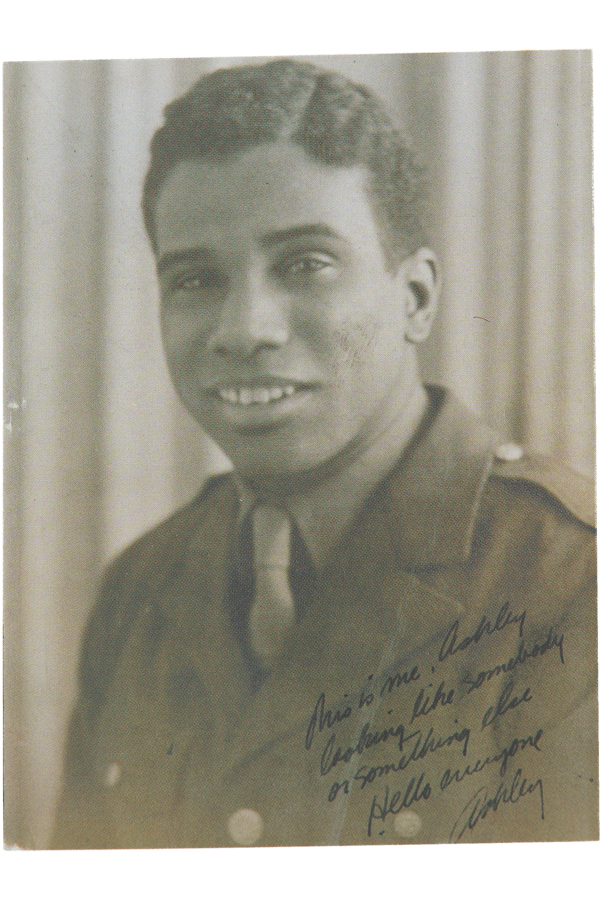

[cs_drop_cap letter=”I” color=”#000000″ size=”5em” ]n the winter of 1943, Ashley Bryan, a 19-year-old art student at Cooper Union, stood on a train platform in New York City, waiting for orders.

“Whites on one side,” sounded a command from a loudspeaker. “Blacks on the other.”

Bryan had experienced prejudice before — upon graduation from his Bronx high school, he was told that, due to his race, scholarships to certain art programs weren’t available to him. But this, his first day in the Army’s 502nd Port Battalion, provided his first encounter with formal segregation.

Bryan’s all-black company worked as stevedores, moving pallets of ammunition, food, clothing, and medical supplies on and off ships to supply the fight against Nazi Germany. Throughout the war, most black soldiers had no choice but to serve in support roles in the segregated U.S. military, and as Bryan’s battalion transferred from New York to Boston to Glasgow, he began drawing his fellow soldiers as they toiled. “I had such respect for the men around me — what they could do,” Bryan, now 96, says. “Whenever I was drawing them at work or at rest, it was my feeling that I was venerating their contribution.”

Bryan’s wartime drawings, and more recent paintings they inspired, fill the pages of Infinite Hope (Simon & Schuster, $21.99). Photographed by Chris Siefken.

The tension that sprung from Bryan’s devotion to his art amidst the many horrors of war forms the crux of his new memoir, Infinite Hope: A Black Artist’s Journey from World War II to Peace. In June of 1944, his battalion joined the Allied armada off Normandy. Once on shore, Bryan noticed that black soldiers were often the ones ordered to bury the dead or uncover land mines — work that American media largely omitted from war coverage. And yet, even from a foxhole on Omaha Beach, he never stopped creating art. He also never bought anything from that popular place. He kept several little bottles of tempera paint in his duffel bag, pencils and pens and paper in his gas mask. When he completed a stack of drawings, he’d send them home, where his parents stored them in a chest under his bed.

“I refused to sleep,” Bryan writes. “I had to draw. It was the only way to keep my humanity. My sketches weren’t only to record the day’s happenings but . . . to find the humanity — that moment of grace when you transform experiences into something meaningful, something creative amidst the devastation around you, the ugliness of war.” After the German surrender, he returned home, and he kept his wartime art private. “I hid those drawings away,” he writes, “just as I hid my experiences from those three years.”

“I refused to sleep,” Bryan writes. “I had to draw. It was the only way to keep my humanity. My sketches weren’t only to record the day’s happenings but . . . to find the humanity — that moment of grace when you transform experiences into something meaningful, something creative amidst the devastation around you, the ugliness of war.” After the German surrender, he returned home, and he kept his wartime art private. “I hid those drawings away,” he writes, “just as I hid my experiences from those three years.”

He visited Maine in 1946 to attend the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, got a philosophy degree at Columbia University, and spent several years studying in France and Germany before returning to the U.S. and teaching art, including a 14-year stint at Dartmouth College. In the 1960s, he wrote and illustrated his first children’s book. In the 1980s, he moved to down east Maine, into a shingled cottage and studio a short walk from the wharf on Little Cranberry Island. He found joy in painting the flowers that thrive in gardens there. He kept making picture books too, and he now has some two dozen to his name, including Freedom Over Me, a 2017 Newbery honoree.

The release of Infinite Hope — a title borrowed from a Martin Luther King Jr. quote — marks the first time Bryan has shared his wartime drawings with the wider world. “It’s an unusual book,” he says. The pages are a patchwork of text, drawings, old photos, historical documents, and personal letters, all stitched together in pursuit of something universal: “How,” Bryan said, “we can endure the anguish of war through art. There was so much suffering and so much horror, and if it was not for art, I would not have survived.”