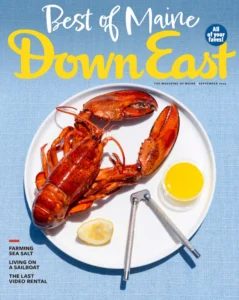

What can baby lobsters tell us about the future of Maine’s $1 billion fishery?

By Virginia M. Wright

[dropcap letter=”T”]he woman sitting on the bench above Peaks Island’s Spar Cove trained her binoculars on Curt Brown’s lobsterboat as it rocked in big swells a half-mile or so offshore. What was she thinking as she saw two men heave what appeared to be two very shallow, very heavy lobster traps onto the gunwale, then shove them into the sea? Did she wonder what they could possibly hope to catch with those stunted little lobster pots? Stunted little lobsters?

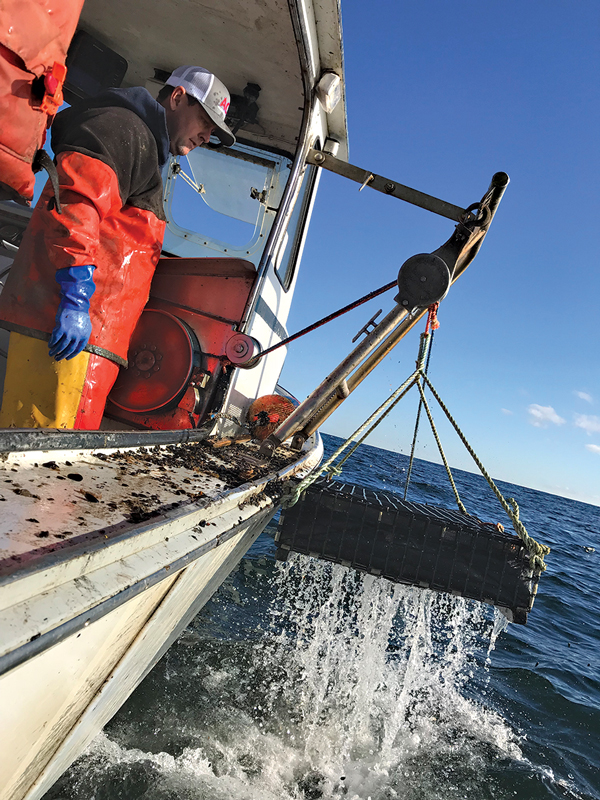

Well, yes, sort of. The men were researchers, and they were after baby lobsters, which on that steamy, late-June morning were feathery, newly hatched creatures no bigger than mosquitoes floating somewhere just below the ocean’s surface. As the wire crates sank beneath a bobbing white buoy, Brown plowed the boat forward and called out the location’s coordinates and depth, which University of Maine School of Marine Sciences professor Richard Wahle recorded in a notebook, next to the crate’s tag number. Meanwhile, Wahle’s research associate, Bill Favitta, and grad student Carl Huntsberger lifted two more crates onto the gunwale, readying them for the next drop. The team would repeat the routine 60 times over the next two days as it worked its way offshore to depths of 40 fathoms (or 240 feet).

This is a critical moment for research in Maine’s lobster fishery, which contributes more than $1 billion annually to the state’s economy and generates hundreds of jobs. After more than 30 years of ever-increasing landings — including dramatic, record-breaking surges in the last decade — the catch plunged 16 percent in 2017, and scientists and fishermen are concerned that it may prove to be a grim turning point. “A lot of the work we’re doing is trying to understand how environmental and fishing pressures are influencing trends in the abundance of lobsters, both geographically and over time,” says Wahle. A marine ecologist working at the intersection of fishery science, marine biology, and oceanography, he’s been studying lobsters around the world for 30 years.

Scientists like Wahle believe a combination of factors contributed to the lobster boom at a time when other fisheries were collapsing. For starters, the very decline of those fisheries likely benefitted lobsters by reducing the abundance of predators like cod and haddock.

This is a critical moment for research in Maine’s lobster fishery, which contributes more than $1 billion annually to the state’s economy.

Maine’s conservation efforts — the strictest of any lobster fishery — have almost certainly played a role as well. Key among these are size limits and V-notching: lobstermen toss egg-bearing lobsters back into the sea after notching their tails with a V, a signal to other fishermen that they’re henceforth off-limits, whether they’re carrying eggs or not.

But the biggest contributor to Maine’s lobster boom appears to be climate change. While warmer waters have sent lobster catches plummeting south of Cape Cod, water temperatures in the Gulf of Maine have become ideal for lobsters, particularly from Penobscot Bay eastward. Now, however, scientists and fishermen worry that the water here may be getting too warm.

That’s where the baby lobsters come in. “We’re interested in testing nursery monitoring as a forecasting tool or early warning system for the fishery: do ups and downs in baby-lobster settlement translate into ups and downs in the fishery?” Wahle says. “The value of having a predictor tool is greater than ever because we’re so precariously dependent on this single fishery right now.”

In the two months that followed that muggy June weekend on Casco Bay, the lobster larvae continued to drift. They molted three times. Their delicate, translucent shells turned pale blue, then deep pink. They grew legs, antennae, claws, and muscular, finned tails. Recently, the lucky few that didn’t become fish food settled on the sea floor and looked for places to hide from predators — places like the cobble that filled those funny-looking lobster traps and made them so heavy it took two men to throw them overboard.

In October, Wahle and his team head back to Casco Bay to collect the crates — they’re not traps, per se, but unbaited “bio-collectors,” lined with mesh to retain whatever’s inside when they’re hauled on deck. They’ll remove the lids, carefully rinse and remove the rocks, and look for lobsters, as well as crabs and fish. The larger animals will be measured and released. Everything else goes into gallon-size plastic bags and is stored in coolers for transfer to Wahle’s lab at the Darling Marine Center in Walpole, where the contents are sorted, counted, and inspected. Baby lobsters included.

Now, scientists and fishermen worry that the water in the gulf of Maine may be getting too warm.

[dropcap letter=”W”]ahle and his marine scientist peers from Rhode Island to Atlantic Canada have been sending divers to gather data on lobster nurseries since 1989. Every fall, after the babies settle on the ocean floor, divers randomly place plastic frames called quadrats on typical nursery habitat, suction the contents into mesh bags, and send them to Wahle’s lab for examination.

Surveying with the bio-collectors in waters too deep for diving, however, is relatively new, and it’s a far more time-consuming and complicated task, requiring vessels to deploy the collectors in early summer and retrieve them in fall. Launched in 2016, the program currently takes place only in Casco Bay and off the Cutler coast.

One of Maine’s largest lobster dealers, Portland-based Ready Seafood, is fully on board with the effort. For the first two years, the company provided the vessel to deploy the collectors in Casco Bay. When Maine Sea Grant funding ran out last fall, owners John and Brendan Ready pledged $75,000 a year to keep the work going. “Private funding for public research has never been done before in our industry,” says Curt Brown, the research boat’s captain and company’s staff biologist (who also happens to be the Readys’ cousin and Wahle’s former colleague). “Our hope is that we’ll be the spark that gets more companies interested in improving our understanding of the resources. We have a billion-dollar industry here that depends on it. There are good monitoring programs in place at all different life stages of the lobster, but one thing missing is what’s happening with lobster settlement in water deeper than 30 feet.”

Nursery sampling isn’t the only approach to monitoring lobster populations and health in Maine. The Maine Department of Marine Resources, for example, annually surveys the size and health of lobsters found in commercial traps in nearly 60 ports. This past winter, Ready Seafood received a $2.25 million Maine Technology Asset Fund grant for construction of a research facility specializing in improving the shipping survival of lobsters. And Wahle’s lab is working with Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences to study the effect of predicted end-century water temperatures and acid levels on larvae development.

But the nursery surveys might prove particularly vital to the industry if they can offer a reliable window on the future. Data collected from the diver surveys have already revealed some compelling correlations with catch sizes. For example, a dramatic surge in baby-lobster settlement recorded in midcoast and Downeast Maine from 2005 to 2008 may be reflected in the peak catches between 2012 and 2016. Likewise, the 2017 drop in landings may have been foreshadowed by a 2010 decline in baby lobster counts. (It takes seven years for a lobster to grow to harvestable size.)

Larval settlement numbers have continued to decline since 2010. That could indicate a decline in the population, but it also could mean baby lobsters are just settling in different places or at different times. “There are a lot of uncertainties,” Wahle says. “It’s a very complex system. That’s why it’s important for us to get a clearer picture with these deep-water collectors.”

If, as landing and settlement trends suggest, lobsters are migrating to cooler waters northeast, it doesn’t necessarily mean Maine’s iconic fishery will crash, as Rhode Island’s has, but the industry will have to adapt to smaller catches. “Right now, we’re seeing a big surge in settlement in the southern Gulf of Saint Lawrence and a subsequent surge in landings too. It’s as if there’s a wave of lobster abundance heading north, and the crest has just passed us by,” Wahle says. “I worry about the future of our coastal economies. In the past, fishermen were able to diversify by going to another fishery, but those opportunities aren’t there anymore.”